Bringing Equality to Music Industry, A Collaborative Project

Back in 2005 musician Kartika Jahja had just released her first independent album, when a major label approached her to get her to sign with them

Back in 2005 musician Kartika Jahja had just released her first independent album, when a major label approached her to get her to sign with them

The deal would include “repackaging” her and here they found a problem: she was neither fat nor skinny. So they told her she either had to lose a lot of weight, or gain at least 30 kilograms to join the rank of “big female singers”.

“They showed me photos, and asked me, ‘Can you be this size?’ Apparently, big singers were becoming a trend overseas,” Tika, as she is widely known, recalled the episode.

“I said, ‘No, I can’t! If I gained this much weight in a month, I’d die.’” But neither could she envision losing that much weight either, “My body is just not shaped that way.”

“So I asked them, ‘Do you like my voice?’ They do. I asked, ‘Isn’t that what’s supposed to matter?’ I was really green at the time, obviously.”

They told her, “This is an industry, dear.”

From discrimination to sexual exploitation, the music industry can be unforgiving to women. Appearance is foremost – talent comes second. They are pretty ornament or sex kittens. This is a norm that has ruled across the globe, Indonesia including.

On stage, where the artists should rule, they are often at the mercy of male audience who demand they take off their clothes, or take photos of their crotch, or rudely grab them, or even offer money to sleep with them.

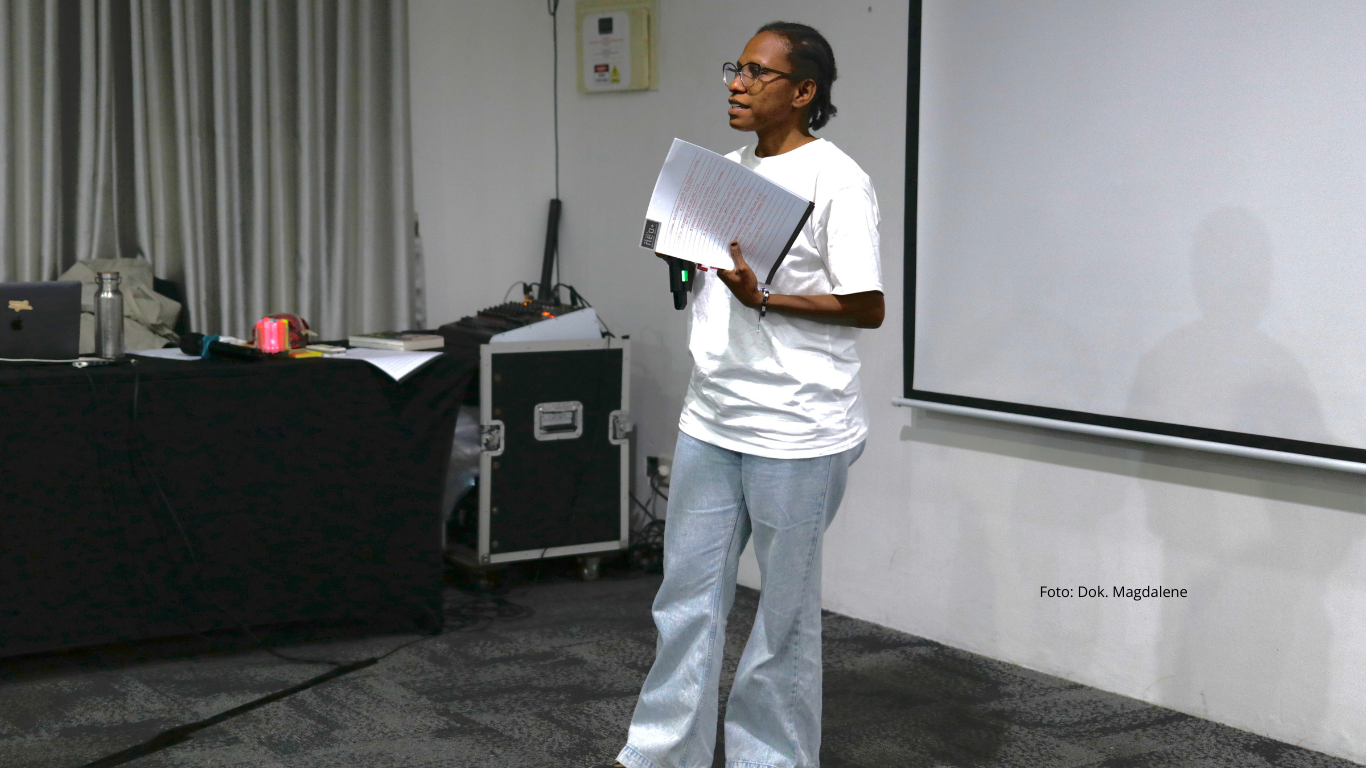

Enter Bersama (Together) Project, a platform to support gender equality through arts. The project coordinated by musician Kartika Jahja, ethnomusicologist Rebekah Moore, and film director Flo Hadjon with the support of the NGO Search for Common Grounds.

In early July, they launched #1Voice4Women a series of four music videos featuring indie artists and bands: Tika and Dissidents, Bonita and the husbands, Yacko and Wonderbra.

“I’m not saying women are the only ones who suffer in the music industry,” said Rebekah, an American national who has been in Indonesia for many years doing research.

“Men suffer as well, but the physicality in measuring success for women is much more extreme. I would say in most industries, but certainly in the entertainment business,” she added.

I sat with co-founders Tika and Rebekah recently to talk about the project and the music scene, and here is the excerpt of the interview:

Tell me how you started this initiative.

Rebekah: The seed for the project started seven years ago, when I met with Tika and fell in love with her music, and we’ve stayed friends ever since. Just a few months ago she contacted me and asked if I could help her with planning One Billion Rising. So I contacted her again after that and told her I had an idea and wanted do something together,

The number one ally this project needs is Tika. Because she understands the politics of gender-based violence, she understands all of the important partners to have in the music scene and in the media, in NGOs, organization fighting for policy change. At the same time, I had a meeting with Search for Common Ground and Scott, the Country Director, said they were also working on something. Within two weeks it was off the ground. But it was another month before we came up with a name.

Why the name?

Rebekah: It was a lot of back and forth between Search for Common Ground, Tika and I, but we finally decided that we needed a name that points to partnership to achieve gender equality. It can’t happen if the only spokespeople are women. It can’t be about women fighting for women, because the root cause is patriarchy. It’s religion, things that are controlled by men. So, in order for women to achieve equality, we all have to work together. And it’s disadvantageous to men too to have gender-based violence.

We wanted something that captures the feeling of collaboration and also gives us plenty of growing room, so if we want to expand beyond music, which is absolutely the plan, we can. We can go into fine arts, into theatres, poetry. But the central idea, the tenet that sort of defines us versus an NGO approach to gender-based violence, and the thing that also separates us from other women’s music programs or groups, is that we’re dealing with gender-based violence always through creative intervention.

It can’t happen if the only spokespeople are women. It can’t be about women fighting for women, because the root cause is patriarchy.

What made you decide on these four artists?

Rebekah: Partly because of availability. No one said no, but they weren’t available and would be available in the next campaign. And this is completely unfunded project. All worked without pay. Everybody donated their time.

We already had a lot of conversations with them as friends about their experiences as women and knew that they would understand where we’re coming from without a lot of directions and would have very personal stories to tell. They also defy stereotypes of the female pop stars. We’re not talking about big, long, curly hair extension and very sexy dress. They’re all beautiful; they’re all sexy, and they defy the stereotypical beauty in the music industry.

Tika: They reflect how women like us, who do not meet the standard of mainstream music industry, are treated. We’re not famous because we lack the talent, but because we don’t fit the criteria.

In a way this can be a lesson to the audience too. Like when they see Bonita, for example, she sounds really good, but a lot of people have never heard of her. There you go. There are many talented women musicians that you don’t know, because we are not given the same opportunities as women who have been molded to meet the existing standards.

Secondly, we chose musicians based on their competency to play live, because they must play live in studio, and they must be able to give an interview.

And we have a long list of musicians, but for this first phase these are the four best suited.

Tika: Yes, very important, because we don’t want to just include people within our own circle. We must expand. The experience of indie musicians is different than the experience of dangdut musicians or pop musicians, etc. If there are mega stars who share the same concern and are willing to speak up about it, we are more than welcome. I want as much experience to share.

If someone at the fame level of Anggun or Agnes Monica, they have the bargaining power to tell the label that this is what they want. We want all artists to have the same bargaining power, but in reality, many are dictated, from what to wear to how much they have to weigh, or even worse, they have to sleep with the producer.

We really want to work with artists at the top level who have that kind of bargaining power over management and label. But we’re not there yet.

And sometimes it’s hard to penetrate the layers of agents and management.

Tika: Or they may be tied by their contracts to not say anything negative about the industry, for example.

Rebekah: We want to go into dangdut, because those environments are much harder for women. Café singers, you literally get offers from men every single night. What women in the indie music go through is mild compared to what they face.

But the nice thing about starting with the indie scene is it reminds us that we’re also complaisant about gender inequality in our backyard – those of us who think we’re progressive, we’re so educated, we’re super liberals and super supportive of the environment and social initiatives except when it comes to women.

And that’s the one thing that Tika and I were surprised about: how difficult it was to pinpoint a male artist who was engaged in this issue in the indie scene. There was no one.

Wonderbra band. (Photo: Iman Fattah)

For female musicians in Indonesia what are the specific challenges?

Tika: This is a global phenomenon, but in Indonesia the common perception is that when boys want to get into music, they have to think if they’re good enough. Am I a good enough guitarist? I am good enough drummer? When girls want to get into music, they have to think: Am I good enough and am I pretty enough?

And when a woman performs in public or stage, the audience thinks it’s their rights to treat her as a public property. You’re on stage, you wear something bold, that means I can touch you. I can take pictures under your skirt.

It happened to me several times. Someone masturbated in the audience. Once when I squatted to hand a member of the audience the microphone, he didn’t hold the mic, he grabbed me!

And this is just a small picture of what’s happening in the music scene, like dangdut, electronic, or café singers. They’re perceived as public properties because they put themselves out there in public.

Yes, there are a lot female musicians, but the pressure we face is different than a male musician. We don’t hear very often a male musician being blamed for the failure of his career, because he doesn’t take care of his body. And when a female musician just had a baby, they often become disposable.

Women are also expected to aspire to marry. We’re not a complete person if we’re not married, and many female musicians stop playing because it’s what is expected by her family, or because it wouldn’t look good to her family.

Why and how can music be an influence in delivering this message?

Tika: Everyone listens to music. I think the trend of human behavior is influenced by the music that is predominant in that time. For example, teenagers are galau (the state of melancholy) because the songs they listen too these days. I listened to Riot Grrrl in the 90s, which is the feminist movement within the punk community at the time, and that’s how I got into feminism in the first place. But if I just stopped there and not learn anything more from it, it wouldn’t amount to anything either. So music opens the door, people will enter, but after that it is beyond our control if they want to dig deeper or leave.

Personally, why are you interested in gender equality issues?

Tika: For a long time, I’ve always felt there’s something wrong. When I was a teenager, I always felt that for me to be able to do the things that I like, like music, travel, or other things that are not conventionally feminine, I had to be one of the boys. I had to shed my feminine side. I had to be masculine. I talked like a boy; I joked like a boy. But as I grew older, I realized what’s happening. I’m not a tomboy. I don’t like being one of the boys. I just want to be a normal woman, me.

From there, I thought, for a woman to be able to empower herself, does she have to be masculine? And even if I acted masculine, does this mean I won’t get raped? Not really. I’m still a woman. I still don’t feel safe in the street, in public space, or even at home.

A bunch of other things made me start writing songs or stories about it, my personal experience, my struggle of being a woman in a male-dominated world. But then I felt it’s not enough to just write songs. I had to do something concrete. I didn’t feel comfortable just writing songs about it.

So five years ago I plunged head first into activism and educated myself. Then I realized that I’ve been looking at things in a very sexist way myself. Like, saying that for women to be powerful, she can’t be feminine, instead of encouraging them to be whoever they want.

I used to not have female friends, because I thought girls were lame. They go to beauty salons, arisan (gathering), etc. And the whole time I was like, if you want to be respected, don’t do all these girly things. Go and do something real! And now I realize that it’s really sexist of me as a woman to think that way.

Now I see many definitions of strong. I see so many strong women now that I wouldn’t know, if I were still looking through the lens of patriarchy.

Rebekah: I’m from an ethnomusicology background. I literally just graduated in March, finished my PhD from Indiana University, after a very long dissertation-writing period. And I did my research on the development of Bali music industry since the first Bali bombs in 2002. This project was heavily influenced by my experience there and by the complete lack of women in the rock music scene there. There was literally one woman for me to interview who was a performer in the rock and underground music scene. I was curious about that, but I didn’t talk about it enough in my dissertation.

My professor actually called me on that: ‘Why don’t you talk about gender?’ I said, ‘Don’t you remember I had one chapter about that one woman involved?’

‘Yeah, but there’s a hyper masculinity in every performance, don’t you think it’s important to talk to men about gender too?’

So that’s where I got part of my inspiration for thinking seriously myself about gender role.

What’s next?

Rebekah: The next phase is research. We’re trying to get funding from a couple of different sources so that we can map out the scene.

We’re going to start with the indie scene, artists who perform regularly who are very active in the music scene, but not at the top level. And hopefully we can branch out to the larger mainstream industry, so we can figure out who are the main allies.

Basically we want to do interviews with as many people as we can. We’re celebrating women in the music industry, but we also want to find out why there’s not more involved, what sort of challenges they face because they’re women. The next project outside of the music industry is the domestic violence capacity and awareness building project.

Our yearlong plan is to have regular programs happening, and it’s going to be specific to the type of audience we’re reaching to and the type of environment we’re focusing on. So for domestic violence, we can’t do a mega concert. That does nothing to violence perpetrators and victims. But for street violence, it can be effective. Or we can work with pengamen (street buskers),

Read this interview with an Aussie writer who talks about the downside of pop feminism and gym selfie and follow @dasmaran on Twitter.