Community-Minded Indonesians Need to Embrace Solitude

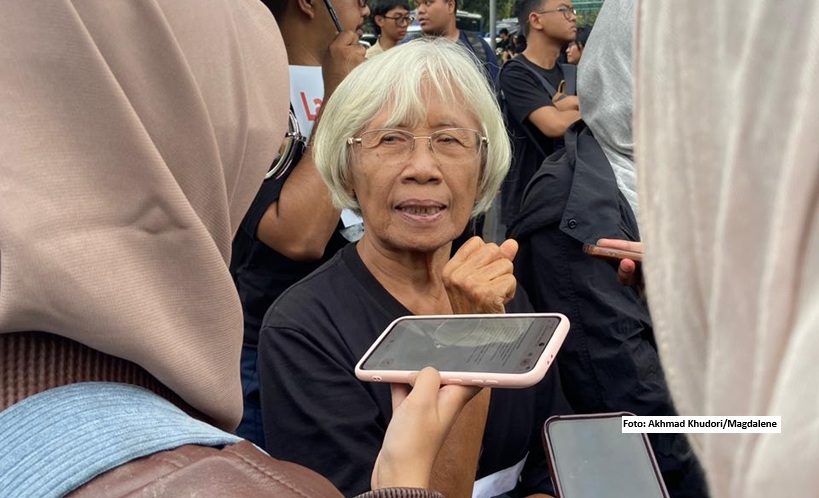

I got a Skype call from one of my Indonesian friends a couple of months ago. She confided in me about being uncomfortable and hurt by her friends who made fun of her, because she had been practicing solitude of late.

“I was called a loner and I hate it! I don’t think Indonesia is a safe place for seekers of solitude like us.”

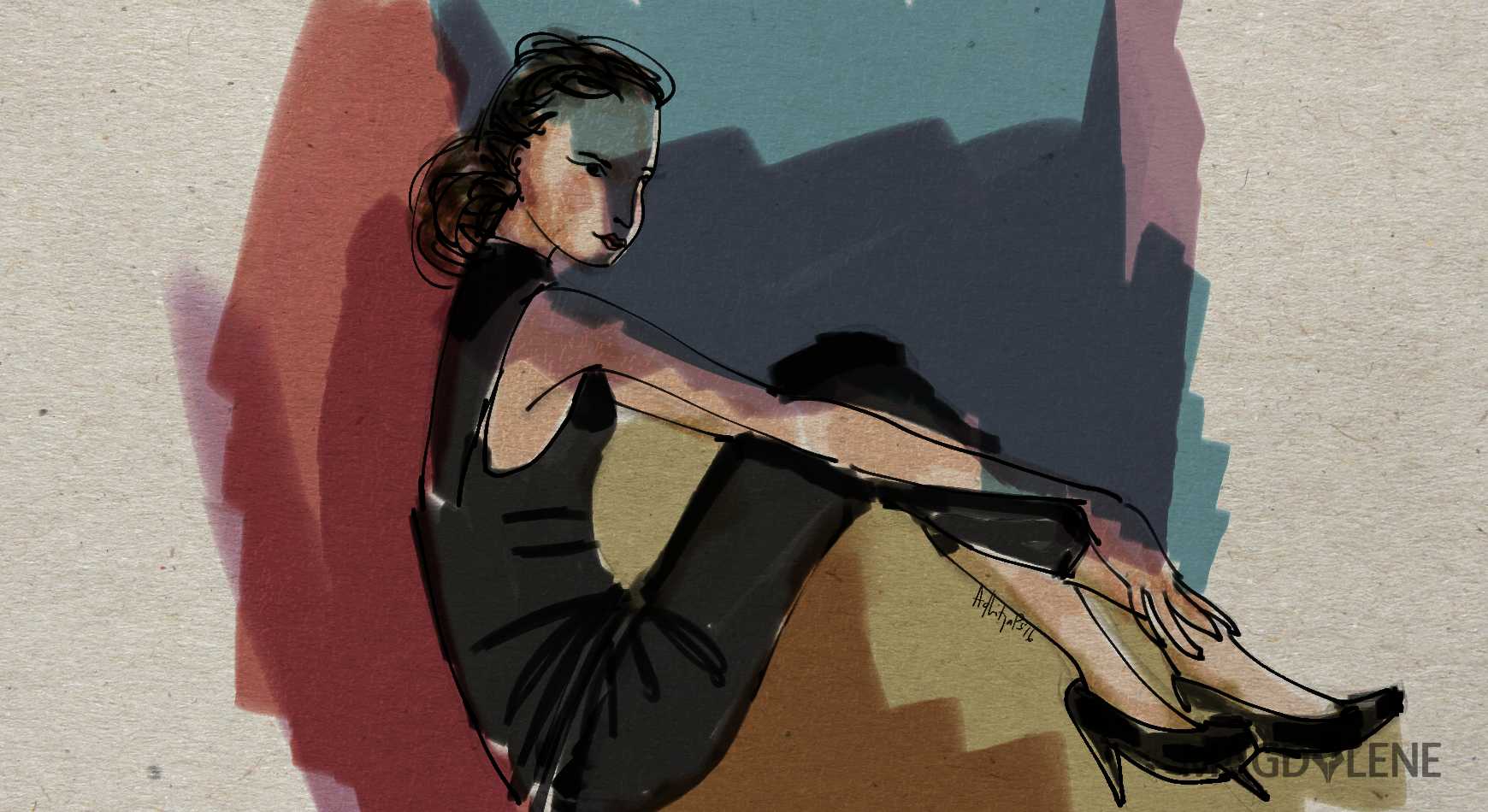

She was spot on. In a society that puts much value on communality, Indonesians can be a bit judgmental towards people who occasionally withdraw from the community. I lived the first 19 years of my life in Indonesia and I am aware how averse to solitude people can be. In my younger years, I often got picked on by my peers for my seeming eccentricity. Sometimes I would wander alone in my town aimlessly, observing the society I lived in. Sitting alone in a library or a café to brainstorm ideas was part of my routine. Often this was done while others looked at me in puzzlement or with pity.

The notion of a close-knit community is a beauty and terror at the same time. The effort that we make to create harmony in our society is profoundly useful. It’s really easy to ask for help without feeling vulnerable, because we believe that human beings are destined to help each other. But on the other hand, for some of us the culture of communality can be a terror. Try to seek occasional retreat from our world of connectivity, and you’d be labeled a loner. Doesn’t matter that the occasional practice of solitude is known to have a reinvigorating effect on your life.

Why are we so afraid of being alone? The answers may vary.

Adam Phillips, the great British psychoanalytical writer, theorizes that our capacity for solitude traces back to the formative experience of childhood, comparing the affinity for solitude to our affinity for certain other people.

“And yet one’s first experience of solitude, like one’s experience of the other, is fraught with danger…. For this reason, perhaps, it is the phobia relating to solitude that for some people persists throughout life.”

For me, it’s the way our society perceives solitary people as sad, while valuing those with a vast capacity for constant connection – and with high self-esteem – as a mark of wellbeing. We worship people who are gregarious or those who are stimulated by the high energy of their surrounding – the extroverts.

But, how, then, do we expect ourselves to produce remarkable ideas if we don’t value those solitary moments that nourish our creative mind? It is well established that solitude and creativity are inseparable. Many great intellects of the past saw solitude as an absolute necessity in their lives. Charles Dickens lived a significant portion of his life in active solitude – a state that enabled him to produce his brilliant books. During ideation, he took three-hour walks every afternoon by himself, and what he observed during these walks would be fed into his writing.

If you look at most of the world’s major religion leaders, you will find that Moses, Jesus, Buddha, and Muhammad went off alone to experience the revelations they later shared with the rest of their communities. No solitude meant no revelation.

In her book How to be Alone, British author Sara Maitland wrote: “We believe that everyone has a singular personal voice and is, moreover, unquestionably creative, but we treat with dark suspicion (at best) anyone who uses one of the most clearly established methods of developing that creativity – solitude.”

But as much as I believe that being solitary is a prerequisite for creative mastery, and though solitude helps me rein in on the chaos of my everyday life, social life remains alluring for me. Making connection with people is wonderful, and I guess that’s what human beings are born for. Collaboration, the opposite of solitude, is something that we must cultivate, after solitude has given us the personal space to produce ideas. Ideas are not viruses, so it should be a part of our daily intake.

Collaboration keeps ideas flourish and develop because they are continuously being shared, reshared, constructed, and reconstructed. I’m not alone in this concept of integrating collaboration and solitude. Take Steve Wozniak for instance. His creativity and intelligence was the outcome of a life of solitude cultivated during his youth, when he explored the nooks and crannies of computers. Later he collaborated with Steve Jobs to create Apple.

So how do we build pockets of stillness into our lives?

You don’t have to be Thoreau, who was notorious for retreating into the wilderness and building his own cabin, where he let his life immersed in nature. The true mark of solitude is eradicating distraction maximally and being content with your own thoughts. Our deepest thoughts, which mostly are the purest and packed with wisdoms, are frequently being neglected because we are so busy executing our superficial ideas. Solitude shows you the paths to access your inner voices.

Practicing solitude is simple. It could be done by taking a walk, going nowhere in particular, shutting off your phones, withdrawing from the social media, and, if possible, meditating.

Embracing solitude in the age of inescapable togetherness is challenging, yet possible. Be prepared to be frowned on, or called a loner. Never care about what people say about your or how they perceive you. After all, how are you going to lead your life, if you don’t listen to yourself and if you keep letting others define your story?

Vidi Aziz is a 21-year-old college sophomore from Solo, Central Java, who is currently living in Michigan, USA. He takes great pleasure in cooking, writing, walking, daydreaming and talking to strangers, delighting in solitary moments and other creative endeavors.