Cyberbullied in Indonesia

Being on social media means exposing ourselves to attacks with invisible weapon, often sharp and unexpected, and, in increasingly growing cases, can end unfavorably. Many of us have experienced cyberbullying, and some of us may have done it while ignorant or not caring of its impacts to those targeted by it.

There are so far no known data and statistics on cyberbullying in Indonesia, mainly because of the unavailability of reporting mechanism. But there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to show that social media users in Indonesia are not immune to this global phenomenon.

Simply check out the media handles of public figures, actors or politicians, or just anyone embroiled in the latest media controversy. In the US, celebrities read the meanest tweets about them by random people in a show segment “celebrity read mean tweets”. Just two years ago during Indonesian election, hatred ran deep between supporters of the two presidential candidates, inciting a sort of social media race. And the controversies over LGBT in Indonesia earlier this year successfully brought out the meanest in people.

Netizens tend to gang up on the “public enemy” of the day, as they did recently when a YouTube video, which shows high school girl Sonya making threats to a traffic police women, went viral. The subsequent attacks on her on social media reportedly left her depressed. And earlier there was Florence, who was cyberbullied after her remark on Path was deemed insulting of Yogyakarta went viral. The most tragic victim was Yoga, who jumped in front of a train after being cyberbullied on Twitter apparently after failing to organizing a concert successfully.

One of my close friends told me about her story of being slut-shamed about a year ago on ask.fm, which she called “the paradise of cyberbullies”.

“It was mostly nasty comments on my looks and that I should be ashamed for not being ladylike, for making innuendos, for making out with my partner,” she recalled her experience. The bully also preached to her about asking for forgiveness from God, and said that her mother should’ve disowned her.

“At first, I took it lightly, but it got overwhelming when it became one question per minute,” she said. “I always put up a tough act in front of other people, because I don’t want to be seen like I was defeated. But the truth is I started having cold sweat whenever I had a new ask.fm notification. I also cried every night during those dark times,” she said chuckling. She later found out that the bullying was done by one person – someone who held a grudge against her over her past relationship.

Another friend, an 18-year-old guy, shared a similar “nightmare” on ask.fm two years ago after he identified himself as pansexual: “The daily question rate on my ask.fm is 200 questions a day and 150 of them are hate-speech.”

The harsh comments, mostly involve the words: homo, anal, butt crack, castration and more.

“I skipped going to campus one day after receiving a message on my ask.fm saying ‘I will follow you to your department’. Another one, a girl, claimed she saw me at a mall and even asked if she could tag along. When I said no, she started sending brisk comments like, ‘You cocky conceited homo…’ et cetera et cetera,” he said.

“Once I also received a threat on Ask from an anti-LGBT person before I went to one university as a speaker. I didn’t take it seriously, so I went as planned. But, the threat turned out to be a real one. A security guard came and told me the event was canceled and behind him was somebody I knew from my previous school, holding an anti-LGBT poster along with many other people who protested. It was really scary,” he said.

Before it was sold to Tinder, ask.fm itself had gone through some crisis following several teens tragic suicide caused by cyberbullying on the platform. But cyberbullying is just as rife on other social media platforms, damaging and even taking people’s lives, as what happened to Amanda Todd and Phoebe Prince on Facebook and Justine Sacco on Twitter.

Characteristics

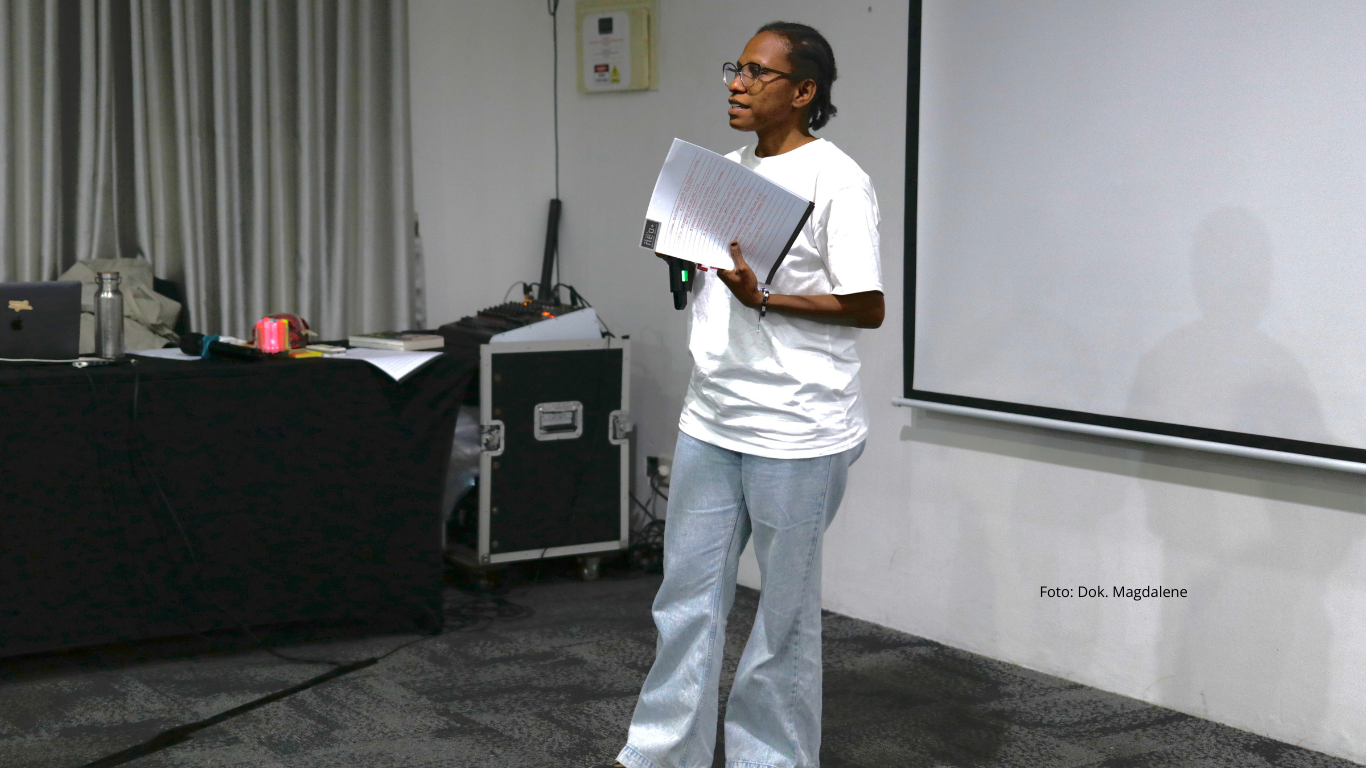

Dhyta Caturani, a woman’s rights activist and a member of “PurpleCode” – a collective that intersects gender, sexuality and technology issues, said in an interview that cyberbullying is just one of the risks when people’s lives have shifted to the digital world.

“In the last decade the internet has become an extension of our struggle,” Dhyta said, adding it was why we shouldn’t see the offline and an online worlds as two separate dimensions.

“What happens online is the continuation of what happens offline, and what happens offline can also be brought to online. One is the extension of the other!” she said.

Technology-based violence is distinct on several aspects: speed, real-time, multiplication, anonymity, difficult threat assessment and limited regulations. Tech-based violence can be inflicted as quickly as the speed of your fingers typing, and it has no time or space limit.

It will follow you as long as you have a smartphone in hand, unlike bullying in school when once you’re home, you’re away from it. Multiplication means perpetrators can easily and rapidly gang-up to attack an individual on cyberworld. Adding complication to the issues is the fact that currently in Indonesia there is no mechanism to report on technology-based violence.

“Once, I received a rape threat online that I even ended up being stalked. I asked my lawyer friend whether I can do anything to report it, but I was told that currently there’s no basis to provide protection to internet users. The police will also argue that it hasn’t happened yet. In most countries, they claim that online threat is such an impossible case because it’s anonymous,” Dhyta explains.

“However, it is important to note that all crimes are anonymous by default. No robbers would wear a nametag on their way to rob your house. It is also incredibly unfair that once the online threat is about bombing, even if it’s anonymous and lack evidence, the authorities will react on it immediately,” she added.

Contrary to the lack of regulations, the purposes of cyberviolence actually varied, from surveillance, control to sexual exploitation. It has evolved into numerous forms as well, such as harassment, hate-speech, cyber-stalking, physical threat, revenge porn, blackmailing, doxing and honey trap.

Doxing is sharing for and publishing private or identifying information about someone on the internet, typically with malicious intent. Honey trap is commonly perpertrated on LGBT people by those who meet them through a matchmaking app, pretending to be a potential partner, only to physically assault them upon meeting.

“I heard stories in a sharing forum here that honey trap occurs quite often. Unfortunately, they can’t do much about it. If they report it to the police, they will likely experience even more injustice because of their sexuality,” Dhyta said.

A lecturer and researcher from Yarsi University, Ade Nursanti, explains that in Indonesia, one of the most common forms of cyber-violence also includes flaming – a hostile interaction between internet users with opposing views – and revenge porn.

“While flaming is a form of cyberbullying related to disagreements over economic, social, political issues; revenge porn is a very personal circumstance. For instance, a high school student who is jealous of his ex-girlfriend would leak her nude photos on social media as a revenge,” Ade illustrates.

“Revenge porn is often linked to blackmailing. In one case, a man recorded a video when he raped a woman. Later, he blackmailed her – threatening that if she did not fulfill his demand, he would leak the video,” Dhyta explained.

Power relations

Kristi Poerwandari, a psychology professor at University of Indonesia, said that although everybody at any age could be a potential victim of cyberbullying, some people are more prone than others.

In general, perpetrators target aspects such as sexuality or basically any peculiar traits of their objects, “It could be being transgender or, for women, not being a virgin. Those who are considered violating the norms are particularly more vulnerable,” Kristi illustrates.

Gender-based cyberbullying commonly attacks on sexuality and appearance, including clothing, face, and body expression.

How one can become a victim of cyberbullying is also closely related to power relations. Kristi noted that, for instance, in school domain, popular kids or rich kids are more likely to become perpetrators.

Kristi describes that bullies who attack individual, whether offline or online, basically aim to “criticize, punish, judge, and isolate” with the intention to destroy their targets. “It’s either because the bullies feel overly confident about themselves, or that deep down, they actually feel hollow. It could be because they were raised in a hostile environment, because they lack attention from their family, or something else,” she added.

In addition to those with stronger social status, today bullies also come in the guise of people who claim to be “holier” or “more pure”, Dhyta said.

Kristi also explains that online people could be very hostile and lacking empathy because of the distance and the fact that the interaction doesn’t happen face-to-face.

“They can be free from social judgment once they hide under the shield of anonymity and, therefore, can be very dangerous,” she said.

How to react

The potential damage caused by cyber-violence is wide-ranging, often leaving deep psychological scars throughout the victims’ lives.

In her research, Ade found cyberbullying victims experience sadness, anxiety, fear and difficulties in concentrating. Most victims feel lonely, depressed and even having suicidal thoughts.

Other than the psychological implication, Dhyta pointed out that cyberviolence may also result in victims facing legal punishment, or going through economic difficulties, as well as submitting to control and self-censorship.

Said Dhyta: “Self-censorship is probably the most fatal impact because one’s very existence basically depends on their ability to communicate their views and the room for personal expressions.”

Here are some strategies to stay safe on the internet:

- Understand the platforms and never share your password

- You can always use pseudonym instead of real names for extra safety

- Manage your personal information carefully, think through which info should and shouldn’t be shared online

- Use geotagging service wisely

If you’re experiencing cyberviolence, you might consider these following steps:

- Ignore if possible, carry on with your lives

- Use report and block tools

- If it’s in the form of harassment/threat, do not erase the evidence, document it!

- Vent to your trusted friends, families or relatives

- Mobilize your allies to back you up online

- Join the movement, put an end to cyberviolence!

Passing along a message from a dear friend: “Before we cyberbully somebody – anybody – it’s important to be aware that we could actually destroy their lives and future, as well as damage their mental well-being”.

*Click here to know more on the cyberviolence against women and girls

Read Ayunda’s piece on the demand for “ideal beauty”.