Facing Up to the Truth About What Really Happened in 1965

It was around this time 31 years ago, in 1984. That day was one of the most historical days of my childhood. It was a cinema day! And it made me nervous, scared and excited at the same time.

The reason for the mixed feelings was two folds. First, I never went to the cinema before, because my religiously conservative parents forbade us, my siblings and I, from watching movies at the cinema. Second, this was a movie about what one social science teacher called ‘the darkest chapter’ in the history of Indonesia. Even though my parents didn’t like the fact that their kids would be in a “sinful” cinema, much less paying for it, they let my two little siblings and me go. They had no choice, as it was mandatory for all kids. The government had forced schools to make students see the film during school hours.

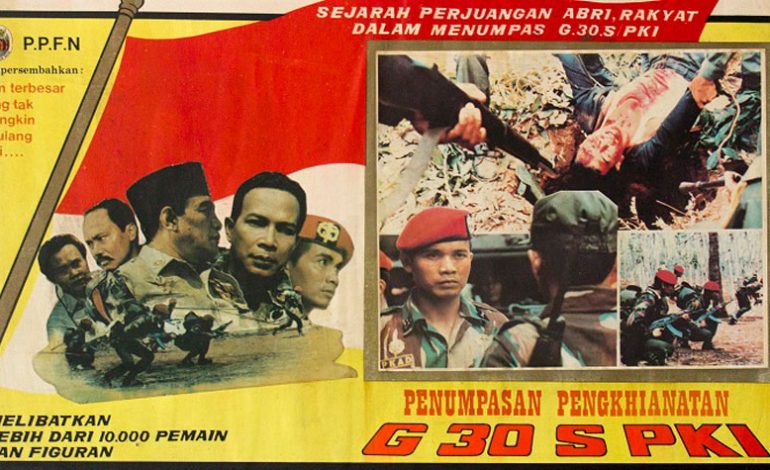

I remember vividly how my dad took the three of us on his 1962 Vespa and dropped us off at the Paramount theatre, a cinema located in West Bandung, to see Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (The Treason of G30s/PKI), the New Order’s propaganda movie that gives its official version on the aborted coup on September 30th, 1965 (Gerakan 30 September or G30S). The movie depicted the coup as being orchestrated by the Communist Party of Indonesia (Partai Komunis Indonesia or PKI) and highlighted the heroism of the army led by General Soeharto.

It was my first movie, and until today it still holds the record as the longest (four and a half hours!) and the most violent, gory, graphic and disturbing film I’ve ever seen in my life. Prior to watching it, we were already familiar with the stories of G30s/PKI told in classrooms by social science teachers.

The movie turned these narratives into “reality”. In horrid and bloody details, it depicted how evil the Communist was. It even had a vivid scene where Communist women castrated the generals and gouged their eyes out while singing a catchy tune, Genjer-genjer – one of several scenes that became stuff of my nightmares days after. The movie, which continued to be televised annually on 30 September until the collapse of the Suharto regime in 1998, was so effective that for years that I believed that every single scene in that movie was based on a true story.

This belief was shaken when I turned 17. It was at that age that I found ways to obtain Xerox-ed banned books, including but not limited to Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s Buru Quartet and Sobron Aidit’s Derap Revolusi. Then, I started to question many things I previously believed in, including the government’s official narratives and history, especially surrounding the 1965 tragic events.

My later exposure to alternative histories of the 1965 events forced me to recall one particular story from my own past. When I was 5, cik (elder sister) Sari (not her real name) came to my life. She was an orphan who lost both of her parents when she was a child, my parents said. So, cik Sari, who was about 16 or 17 when she first arrived at my parents’ house, moved in with my family in Dayeuh Kolot.

Cik Sari was kind, quiet and soft-spoken. She was frail and spent so much time daydreaming. One evening, we had fish for dinner and cik Sari refused to eat. She didn’t say anything, but her face turned as white as a sheet and her body shook.

One day, while picking nits off of my hair, she told me that when she was around my age she saw her parents killed and dumped at Bengawan Solo, a river that flows through the border of Cepu, her hometown, and Ngawi. The river turned red from all the bodies floating in the water and, according to cik Sari, the fishes there grew significantly larger afterwards. She stopped eating fish ever since. After spending six to seven good years with us, cik Sari eventually left for a missionary school. She, however, never led a normal life and sadly died young in her early 40s.

Years after she recounted it, I finally understood the context of her story. Cik Sari was one of millions of innocent children who lost their parents to the 1965-1966 massacres.

The 1965 tragedy was a complex event. “True” history regarding many aspects of the event is still incomplete. While there have been research, literature and reports done on the subject, there is a need for new truth narratives about what happened in Indonesia around 1965-1966, such as accounts of the witnesses, the executioners and the victims in The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence movies and in a recent edition of the Bhinneka magazine (Setengah Abad Genosida ‘65).

What is very clear here is that the massacre did happen. It is undeniable that mass killings, torture, imprisonment and other atrocities against people accused of being “communists” had swept across Indonesia following the seize of power by General Soeharto on Oct. 1, 1965. It is the truth that the massacre of 1965-1966 was a humanitarian tragedy we must collectively acknowledge. It is the truth that the victims of this past massacre are still the victims of today’s Indonesia. It is also the truth that injustice happened and continues to happen.

Once I opened my eyes and my ear, I started seeing and hearing cik Sari everywhere. There are many cik Saris out there. Their inaudible voices are calling for justice. With silent hearts, they are begging us to make them feel human again.

Merlyna Lim is a Dayeuh Kolot-born Indonesian who currently resides in Canada. She is a scholar, a professor, a jazz-dut singer, an amateur cook and a perpetual doodler who believes in pursuing justice and truth, without which there would be no basis for human hope.