How Energy Supplying Programs in Remote Areas Can Have Exploitative Effects to their Beneficiaries

Women living in remote areas in the eastern part of Indonesia face a tough challenge called energy poverty. The challenge arises because of limited government resources that renders the State Electricity Company (Perusahaan Listrik Negara) incapable of providing access to electrical energy to these areas. There are still 30 million Indonesians, mostly living in eastern Indonesia, who have no access to electricity, compared to the 227 millions others who have already had access to it.

Energy poverty affects women more severely than men. The lack of access to electrical energy makes it difficult for them to do domestic activities in the household. In the dark, cooking is more challenging, they cannot do their craft works like weaving, and they might be more vulnerable to sexual violence.

Some development agencies have attempted to address energy scarcity in remote areas in Eastern Indonesia by distributing solar-powered lights, particularly d.light S20 and d.light 300, both of which have practical design and are portable particularly for the women. With maximum heat from the sun, the lights can last eight hours, and for four hours if the sun is in minimum heat.

The lights are not given to the women for free, however, as the agencies believe free handouts will not change the women’s lives for the better. The women have to buy it at a price that range from Rp 200,000 to Rp 500,000, with a one-year warranty. To distribute the lights, the agencies recruit some women to become agents, offering them sales commission to supply their household income. The program has been widely implemented in Eastern Indonesia, especially in East Nusa Tenggara and Papua.

Admittedly, the program has provided a glimmer of hope for the lives of local women in Eastern Indonesia. More than 62,775 people have benefitted from the technology, 388 women have been recruited as agents, resulting in an average 12 percent increase in the sales of solar-powered lights.

But this is not the whole story.

In my view, the program will create a new dependency on the use of technology among the women. Solar-powered lights do not last forever. Their lifespan is typically about a year. When the lifespan of the light end, the women will inevitably have to spend their money to replace them. By then they are already “addicted” to the various pleasures and conveniences of life offered by the light, so it might take some adjustment to life in the dark again.

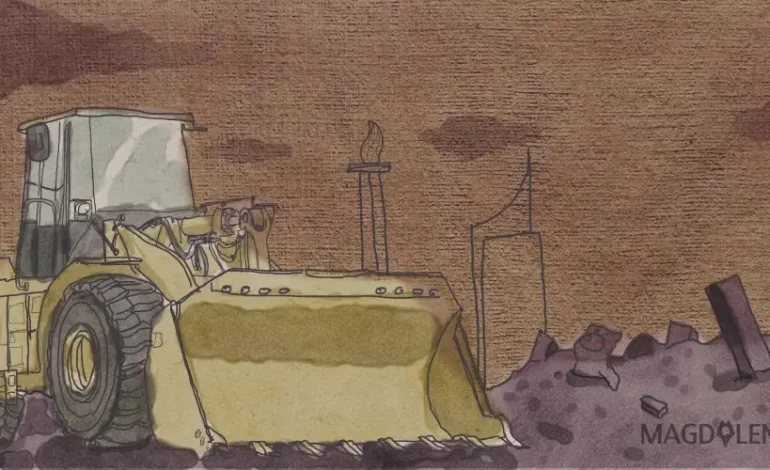

On the other hand, the situation benefits the solar-powered light distributor. The lights are imported from China and the United States. The distributing agency profits from the inability and helplessness of the women, creating a “new economic system” in remote areas of Indonesia out of their new dependence on the technology.

Furthermore, mitigating climate change has been used as one of the reasons behind light distribution programs, immediately raising the program’s credibility at the international level at a time when there is a big interest in new and renewable energy. But as the agencies and companies producing the lights enjoy greater support, more women will be exploited economically.

This reminds me of a similar situation in the mountainous region of Puncak Jaya, Papua, where the normally barefooted local tribespeople were supplied with footwear by some well-intentioned agencies. After the shoes were worn out and the supplies ended, the tribespeople must adapt again to living barefooted.

If the agency really wants to help local women out of their energy poverty, they had better used the mechanism of energy democracy and empowerment. The mechanism allows local women to become actively involved in managing technology and determining the use of technology for their prosperity. They will gain great resources and authority to get involved in determining their own lives, without having to rely on other agencies. In the concept of technology distribution, only a few women are selected to be agents in distributing the solar-powered lighting technology. The rest are only active consumers.

The agencies claim that as “technology agent, the women are empowered by taking part in various trainings such as on managing household finances, public speaking and communication skills. But the “empowerment” efforts do not directly address the issue of energy poverty. The effort remains artificial and insubstantial to the problems faced by the local women.

What would be better is if the women are empowered to create light technology or other energy sources independently. They are then taught to utilize and maintain the existing technology. Constraints such as human resources and the readiness of the quality of local populations can be overcome if the relevant agencies are truly committed to removing local women from energy poverty.

Morocco is the best example of this. Greenpeace developed a DIY solar cooking set in single households and to create decentralized solar energy utilization. They recruited 20 volunteers to be in charge of training residents to maintain the technology. The implementation of solar energy for cooking in communities in Morocco is an example of how the full use of energy by the will of the community can contribute to the energy independence of a country.

Local women living in rural areas do not have the political power to voice their hardship. Their weakness and powerlessness are vulnerable to exploitation by certain parties, so they need to be liberated from “new economic systems” that can potentially exploit them.

Abdullah Faqih is a student of Universitas Gadjah Mada Indonesia majoring in Sociology who is interested in indigenous people related issue.