How “Ideal Victim” Stereotype End Up Hurting All Victims

Nowadays, social media platforms often resemble a virtual courtroom, where everyone can assume the roles of judge, witness, or expert witness almost at their convenience. It’s not always bad, as I’ve seen cases initially raised on social media catching the attention of law enforcement and proceeding to the actual court of justice. In some instances, social sanction translates into real verdicts, and justice is duly served.

However, I’ve also observed instances where the public courtroom swiftly changes gears from condemning alleged perpetrators to bullying the supposed victim. Voices that initially clamoured for justice morph into harassment, adding more trauma experienced by the alleged victim. A common catalyst for this shift is the revelation of the victim’s personal life and information. It’s as if the victim’s flaws or deviations absolve all crimes committed against them.

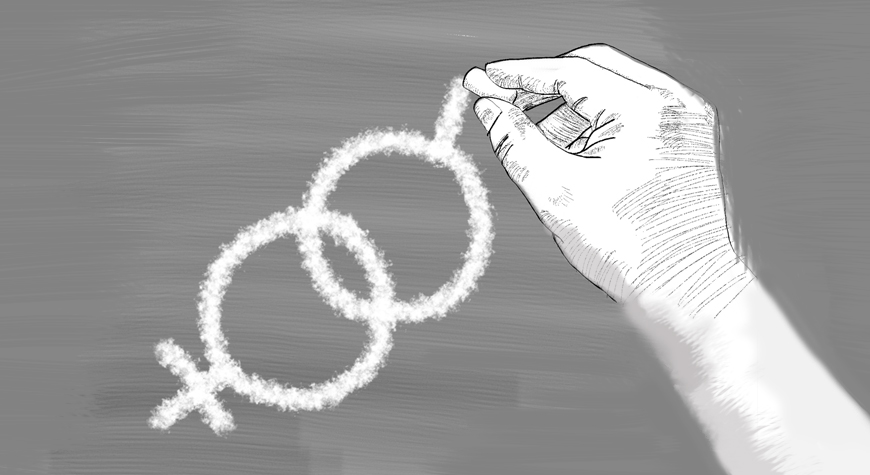

In his seminal work from 1986, Norwegian sociologist and criminologist Nils Christie delineated the socially constructed notion of the “ideal victim.” He identified five attributes characterising this ideal victim: weakness, engagement in respectable activities, lack of involvement in blameworthy actions, and victimisation by a physically stronger perpetrator with no ties to the victim. On the contrary, “non-ideal victims” typically lack these attributes.

Also read: Festivals Must Do More to Address Sexual Violence

This construction of the “ideal victim” strongly influences how both the public and law enforcement perceive and treat victims. Those who closely align with the ideal victim criteria often receive more empathetic and favourable treatment, while those who lack some of them may be accused of being “phonies” or “illegitimate victims.” This raises questions about our ability to embody the principle of “adil sejak dalam pikiran” (justice begins in the mind), given our inherent biases.

While judicial courts and law enforcement are mandated to maintain neutrality and treat both victims and perpetrators impartially, the public is not bound by the same obligation. People are free to take sides, as long as their stance does not influence the legal consequences or compensations received by either party. Nevertheless, the model of the “perfect victim” and associated biases often compel individuals to become perpetrators themselves.

Among the many ongoing and past cases, one prevalent example is catcalling stories. Women often complain about being catcalled and wolf-whistled on the street while going about their daily lives. What changes, based on my observation, is that some women start to attach photos or at least provide descriptions of what they were wearing when they experienced such harassment.

This behaviour, from my perspective and understanding, is one way to challenge the stigma of the “deserving” victim. In conservative nations like Indonesia, women who wear slightly unconventional outfits are often seen as justified targets for harassment instead of victims. This is because they are perceived to violate the “lack of involvement in blameworthy actions,” with the “blameworthy action” being “wearing something revealing or unconventional.” Although sharing outfit details can signify that “every woman can be a victim,” it can also be interpreted as an attempt to fit into the “ideal victim” criteria, thereby strengthening their position and justification for posting said complaints. Imagine if a victim posted a picture of herself wearing a slightly revealing outfit when harassed; it’s likely that many comments would blame her instead of consoling her or condemning the perpetrators.

My concern lies in how society treats victims who do not conform to the “ideal victim” stereotype. It adds a new “acceptable” template, if not a burden, for women to prove themselves conforming to the widespread societal beliefs before posing complaints or sharing their experiences. Now, it’s the clothes they wore, next might be timestamps, whether they are with companies or not, and other unreasonable standards. For people with a harasser mindset, there are always justifications for their actions. Some might even dig up old posts to find any sort of blameable actions to hurt the victim’s character; that they “deserved” said harassment and are unworthy of support. The goalposts, especially for women, are always moving.

Furthermore, it also strengthens the notion that only “ideal victims” are safe to share their stories online and worthy of support. I’ve seen instances of people sharing horrific stories of abuse they experienced online, only to be met with scepticism and interrogation before receiving any support. While this may be a preventive measure due to the prevalence of fake stories that sound like creative writing assignments, it can deter any victims from sharing their stories or just getting things off their chests online.

Also read: Healing from Child Sexual Abuse is Often Difficult but Not Impossible

With ambiguous standards, ever-moving goalposts, and unempathetic scepticism, an “ideal victim” is just a mere illusion–an unconscious bias that perpetuates impunity for harassers. If this continues, we are fostering a hostile environment for everyone to live in.

Do we want to continue absolving any harm that befalls them simply because they fail to meet our subjective standards? Or can we start being more empathetic and create a safer environment for everyone?

Ursula Florene writes about almost anything except herself.