Legislators Having the Last Laugh, All the Way to Bank

The presidential standoff between the two candidates that followed the July 9 election has provided one of the biggest tests to Indonesian democracy. With one president unwilling to concede defeat, regardless the results of a number of credible pollsters, Indonesians are kept in a limbo until the General Elections Committee announces its official results on July 22.

But something equally disturbing took place in Parliament recently, when it passed a bill that will limit (or benefit, depending on the election official result) the new president’s authority.

Just a day before the July 9 presidential election, the House of Representatives (DPR) passed a bill to revise an internal regulation, the Legislative Institution Law, also known by the shorthand MD3.

On the day it was passed, legislators from parties that support presumed president elect Joko “Jokowi” Widodo walked out of the plenary meeting in rejection to the bill. But they were outnumbered, so the new regulation was passed anyway.

Critics say the revision to the 2009 Law will diminish the House’s performance in the future instead of improving it, as claimed by the lawmakers. The Coalition of Civil Society, which groups several renowned NGOs, called the Law repressive, discriminative and corrupt.

Lawmakers from presidential candidate Jokowi’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) suspected that the new law is aimed at inhibiting the party’s influence in the House’s 2014-2019 term. Though PDI-P has the biggest members in parliament at 19.4 percent, it has fewer parties in the coalition to support Jokowi, compared to the total number of parties that support his opponent Prabowo Subianto. This has raised concerns that if Jokowi does get elected, a strong opposition in parliament will continue to impede his administration from running an effective government.

Below are the reasons why the revised law is problematic:

1. It creates red tape for an Anti-Corruption Commission’s (KPK) investigation into legislators. Article 220 of the revised law stipulates that the commission is required to get the President’s permission before probing a lawmaker. This, critics say, is discriminative and unconstitutional, as every citizen has the same legal right. They raise suspicion that it is aimed at hampering the legal process and KPK’s work in fighting corruption.

The law is also discriminative as it only applies to members of the House of Representatives, not the Regional Representatives Council (DPD) and the Regional Legislative Council (DPRD).

2. It limits women’s roles in Parliament by eliminating the stipulation that emphasizes on the importance of women representation, particularly in the leadership of parliamentary bodies/commissions.

3. It changes the system so that the political party that won the most votes during the legislative election does not necessary become the House Speaker. In the new system, this position is decided through a voting mechanism. The same mechanism applies to heads of commission, budget committee, legislative committee, honorary council and general affairs committee.

This will likely benefit Prabowo’s ‘permanent coalition’, which will have the full right to reject or accept any bill, and even to block the president’s policy if necessary.

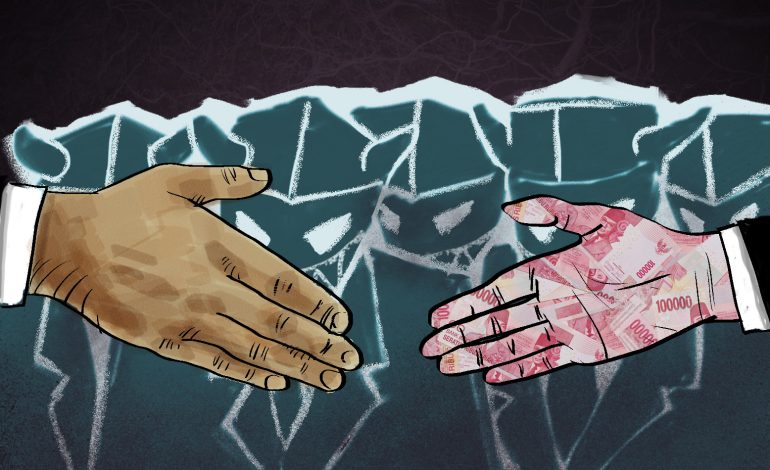

4. It legalizes gratification, because for every proposed bill and project, House legislators are entitled to get ‘aspiration/constituent region fund’. Initially, the right to aspiration fund is in the form of proposing program. But later on, it was changed into the right to get a certain amount of fund allocation based on the agreement with the government.

Worse still, there is no clear implementation mechanism and accountability regarding the right. And to add to the fishiness of the whole thing, this privilege only extends to House legislators, not DPD and DPRD.

In short, these four points alone will give Parliament the biggest authority since the reform era began sixteen years ago.

Fortunately, PDI-P and the Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) said it would file a judicial review for this law to the Constitutional Court.

Now it is up to us to safeguard this process by continuing to raise this issue, so that the Constitutional Justices are aware that the people will not tolerate such a blatant abuse of power in the legislature anymore.

Follow @heradiani on Twitter