Lest We Forget, The May 1998 Riot

“Eh… Cina (Chinese)! Here’s a Cina! You’re a Cina, huh??”

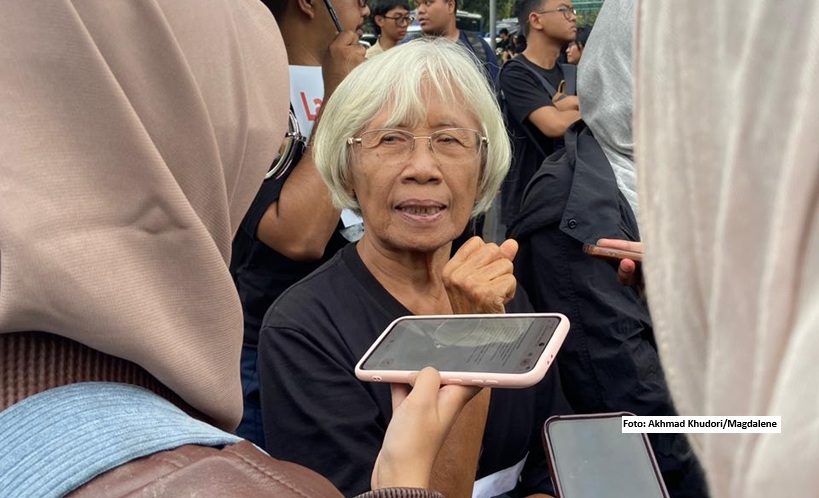

The derogatory term was screamed at me a number of times during the riotous days of May 13-14, 1998. Sometimes the tone was full of threat, sending chills up my spine. Wearing wide sunglasses, hat and a vest with “Forum Keadilan journalist” written on it, I felt protected. Several journalist friends and photographers felt the same way and we got each other’s back. On my chest hung my identity card: Sen Tjiauw, Forum Keadilan magazine.

If it weren’t for the nametag or the journalist status, I might’ve been a target like many other Chinese Indonesian women. In those few days where chaos reigned, it would’ve been a suicide mission for most people especially of Chinese descent to be out and about to observe what was happening across the city.

Reminiscing the three days of violence is like reliving a nightmare. The horrifying dream was marked by a mass riot and people’s rage towards the shooting of Trisakti University students. Violence broke out in Senayan, Slipi and Grogol areas in Central and West Jakarta.

When the riots broke out in Trisakti and Tarumanegara Universities, some friends and I fled for safety like the thousands of student protesters. Our eyes were burning from teargas, and sounds of gunshots and hails of stones were deafening. I picked up some empty bullets to bring home. I also attended the procession to honor the four Trisakti students who died martyrs from the military’s bullets. And then our worst nightmare came true. Soon the whole country was raging with violence. In a number of big cities, the fury over military’s brutal action triggered protests and unrests.

I was a young journalist at the time with four or five years under my belt and I barely had any fear. Two years before, I covered the July 27, 1996 unrest following the attack of the Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI) headquarters. I had experienced being among security officers and upset and anxious protesters, and dealing with teargas. I knew enough to equip myself with bottled water and to smear toothpaste under my eyes.

We journalists spent most of our days out on the field, returning to our office briefly to coordinate with our colleagues before going back out. We roamed the streets on motorcycles with photographers or office drivers, slipping through street blockades to find out what was going on in Jakarta at the moment.

I remember going with the late photographer Krus Haryanto, driving to Jembatan Besi, Jelambar and the neighboring areas in West Jakarta – the city’s sky was black in smoke. I joined several photojournalists around Glodok and Harmoni Chinatown, and came across a group of people who were looting a fruit store at Harmoni. A man carrying a box of fruits stared at me as I watched from the sidewalk. He did not say a word but handed me an apple. Trembling, I refused his offer. It was as if he had asked me to join a conspiracy.

It was there on that street corner that people were shouting “Hey, you Cina!” at me. I didn’t dare to reply. All I could do was showing them the huge nametag on my chest. I don’t remember all the photojournalists who were with me at the time, but without them, my story would’ve been much different.

On those days, it was hard to describe my feelings as an Indonesian citizen. It was difficult to react toward the savagery of groups of people who came from out of nowhere. Standing on a pedestrian bridge at the Harmoni shopping district, we witnessed how the quiet ghost town blanketed in smokes and heat from burnt tires suddenly turned into a festival of looters. From every corner of small alleys, groups of violent-looking men appeared. It remains a big question today where those people come from. I tried to recall my feeling when seeing car showrooms around Harmoni-Kota engulfed by fire, and I felt suffocated by the sadness.

Victims of looting, robberies and the brutalities were not the only ones affected during the violent period. A good friend of mine who is now an editor-in-chief of a newspaper looked dazed for days. I took his hands and they were trembling hard. What we witnessed and took notes of was beyond our capacity to comprehend. Luckily, my network of journalist friends who covered politics and legal affairs were solid as a rock. We become each other’s support system, keeping each other calm.

We supported people we thought were good, people like Amien Rais, who was hailed as the Father of Reformasi. We gave him a lot of space in our publications, quoting him and rooting for him in the early years of his post-reform political career. Many ended up regretting the decision. He turned out to be a huge disappointment.

I interviewed a young father who lost his wife and two young children when their shop house in the predominantly Chinese Kelapa Gading area was burned down. I can still smell and feel the dust and the debris when the father, choking back tears, walked with me through the ruined shell that was once his family’s home. I wonder where he is now and how he is holding up. I am certain he never looked at his country the same way again.

A few months after the May tragedy, I flew to Pontianak in West Kalimantan to meet a number of rape victims, but I never got to see them as they were too traumatized to share their stories.

Sixteen years have passed and the May tragedy remains a mystery. No one has ever been accounted for, and the riot victims were never compensated fairly. The state has clearly abandoned the people.

The Joint Fact-Finding Team (TGPF) found that the Indonesian military let the chaos happened to have an excuse to take over power. One of the team members Nursyahbani Katjasungkana, said then Jakarta Military Commander Sjafrie Sjamsoeddin must be held accountable. The meeting on May 14 at the Army Reserve Strategic Command Headquarters, according to TGPF, could reveal clearly who the intellectual actors were behind the May riot and what was the motif behind it.

Years later, Nursyahbani expressed her regrets that none of the four presidents who came to power after Reformasi had been able to follow up the team’s recommendation, particularly on victims’ rehabilitation and compensation. A lot of the victims have instead been stigmatized as looters. It is an abomination, she said.

Nursyahbani’s disappointment is our disappointment. To this day, the May tragedy remains an unhealed wound.

About Sensen Gustafsson

A former political journalist at Forum Keadilan weekly magazine based in Jakarta, Sensen moved to Sweden five years after Mei 1998 riots. She is currently a full time working mother of two kids.