Let’s Have More Elsa, Maleficent and Merida: A Mother’s Take on Fairy Tales

“Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know.”

The mantra sticks with Elsa, the princess – and later the queen – in the animated film Frozen (2013). She turns everything into ice with the touch of her hand. For years Elsa is kept inside the confines of her room, much to her sister’s, Anna, confusion. But Elsa’s dangerous strength is considered an embarrassment and a curse. No one must know about it.

I’m sure many mothers are worried with the stereotypes of princesses in Disney tales who are often described as submissive and shackled, finding freedom only when meeting their princes charming. These story lines give birth to the term “Cinderella Complex” – the woman being dependent on others, usually her partner, or cannot end the relationship even when it turns abusive.

This is a real psychological problem. And it raises the question whether those stereotypical princess tales women grew up on is one of the factors causing this. A friend of mine even vowed not to give her daughter Barbie dolls, or allow let her to watch films of Disney princesses.

I, too, have the same concern for my four-year-old daughter. But I don’t want her to grow up a stranger to the popular culture of her own generation. So I decided to take her to see a princess film. Frozen, one of the most watched animated films ever, was our first choice.

Despite the romantic setting and the happy ending, it is a less than a typical fairytale story. The main character Elsa, the one with the icy touch, is not romance-crazy, unlike her sister Anna. She sang the song “Let it Go” (that ubiquotous song) as a form of rebelion against his father’s order that is stuck in her head: “Conceal, don’t feel, don’t let them know.”

It is a reminder to the struggle women face every day – the situations in which women have difficulties expressing themselves. There is an entrenched cultural construct that shun women who are “too smart,” “too bright,”,“too strong,” or “too brave.” Women “must be sensible to fit in”, to be accepted. Isn’t that another form of Elsa’s father’s mantra?

The song “Let it Go” also appeals to the LGBT community, as it calls people to be open and to express themselves. We know that acceptance of LGBT people are still low in Indonesia. Families ask them to hide it, or even to “cure” themselves of homosexuality, which is seen as a disease.

The story of Frozen is simple, but important for mothers like me, as it allows rooms for interpretations that are friendly to women and LGBT. It’s not just a beautiful story with “empty calory” of values for my daughter. Even if she has yet to understand the deeper interpretation, at least she sees the gestures and expressions of a woman who is full of confidence. Like when Elsa sings “Let it Go” while climbing a snowy mountain. Like when Anna insists on looking for her sister alone.

After graduating from Frozen, we moved on to Maleficent (2014), a live action film that is an adaptation of the Sleeping Beauty tale. It is amazing how the film turns Maleficent from the bad to the good guy. Angelina Jolie plays the role in perfection. Maleficent, who usually is depicted as a one-dimensional witch, is now portrayed as a person with compassion. The story overturns the black and white nature of the princess tale.

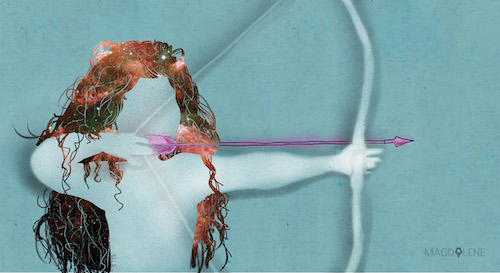

But before Maleficent, there was Brave (2012), a film with characterization more powerful than the aforementioned ones. Set in a kingdom located in the highland of Scotland, the film centers on Merida, a non conventional princess in the history of Disney.

Backed with incredible cinematograpy and music scoring, Brave is an extraordinary film. It is a lesson of feminism disguised as child movie. Merida is depicted as a princess who despises the attribute and obligation as a princess. She loves archery, horse riding and rock climbing. She wants to inhale the air freely and she wants everything that goes against the teaching of her mother, Queen Elinor.

When it is time for Merida to face the matchmaking competition, she cunningly chooses archery as the requirement to win her heart. But on D-day, when three young men from prominent families finished with the competion, Merida enters the arena as the fourth participant of the competition. As predicted, Merida beats the other boys and becomes the winner of matchmaking contest to wed herself. In doing this, she succeeds in seizing her own destiny.

In Frozen, Anna, whose heart was frozen by Elsa’s power is not cured by a kiss of a man who falls in love with her. The act of true love that thaws her is none other than the affection of her sister, Elsa. The same goes with Maleficent. Aurora the sleeping princess is not awaken from her sleep by a kiss of a handsome prince who stumbles upon her. She is woken up by a true-love kiss from Maleficent, a creature who puts a spell on her but is also her fairy godmother.

I’m exhilarated to see how the three films have moved away from the antiquated descriptions about women. There is no excessive antagonism between women. The dramatic elements in the films are not formed by bullying the main characters, like we see in nearly every version of Cinderella.

As opposed to the characterization of the step mother in Cinderella and Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty, Maleficent in the film Maleficent can be seen as the introduction to the ethics of care, which is voiced by today’s feminism. On the other hand, Anna and Merida show our girls women who express themselves with conviction and choose their own destiny.

As Merida says at the end of Brave: “There are those who say fate is something beyond our command. That destiny is not our own, but I know better. Our fate lives within us, you only have to be brave enough to see it.”

Maulida Sri Handayani is a mother. She studies at Driyarkara School of Philosophy, Jakarta.

This article is originally written in Indonesian. Read it here.