The Iceberg Beneath Veloso’s Case: Unjust Punishment, Long Awaited Freedom

Dozens of journalists jostled for position as a black Toyota Hiace pulled up at Gate 6 of Soekarno-Hatta Airport, Tangerang, on Tuesday (17/12/2024), at 08.45 PM. Cameras focused on the left side of the van, anticipating the emergence of a figure who had dominated media headlines.

After five tense minutes, an immigration officer opened the door, and Mary Jane Veloso stepped out, capturing everyone’s attention. She smiled at the crowd of journalists, who surged forward to snap photos and record videos as she made her way into the Umrah Lounge in Terminal 2F. A press conference was held there to announce her transfer to the Philippines.

Also read: Heroin Queen? Merry Utami’s Life Tells a Different Story

After spending 14 years in detention in Indonesia, Veloso was finally returning to her home country. During the press conference, she became emotional, shedding tears yet managing to express her gratitude. “I want to celebrate Christmas with my family. So, thank you, assalamualaikum,” she said in Indonesian, concluding her four-minute statement before heading to the waiting room.

Veloso’s ordeal began in 2010 when she was arrested at Adisutjipto International Airport, Yogyakarta, with 2.6 kgs of heroin in her suitcase. Months later, an Indonesian Court sentenced her to death. Her case stagnated for years: President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo denied her clemency in 2014, and the Supreme Court rejected her judicial review request in 2015.

Throughout, Veloso maintained her innocence, claiming she was unaware of the drugs in her possession. She stated she was deceived by fellow Filipina Maria Kristina Sergio, who had offered her a domestic job in Indonesia.

Veloso explained that Sergio handed her the suitcase, which she did not realize contained heroin. The Guardian cited Veloso’s letter to then-Philippine President Benito Aquino in 2015, in which she wrote. “We’re poor, and I wanted to change our life, but I could never commit the crime they have accused me of.”

After more than a decade, Veloso’s story has reached a resolution. Her return has been met with widespread positivity, and she no longer faces the threat of execution, as the Philippes has abolished the death penalty.

Yet, her case underscores a troubling reality: the exploitation of women as drug couriers by trafficking syndicates. While Veloso’s story received media attention, many other women remained imprisoned under similar circumstances, their cases largely ignored.

Also read: Ex-Convict Finds Road to Repentance, Thanks to Australian on Death Row

A Two-Decade Detainee Named Merri

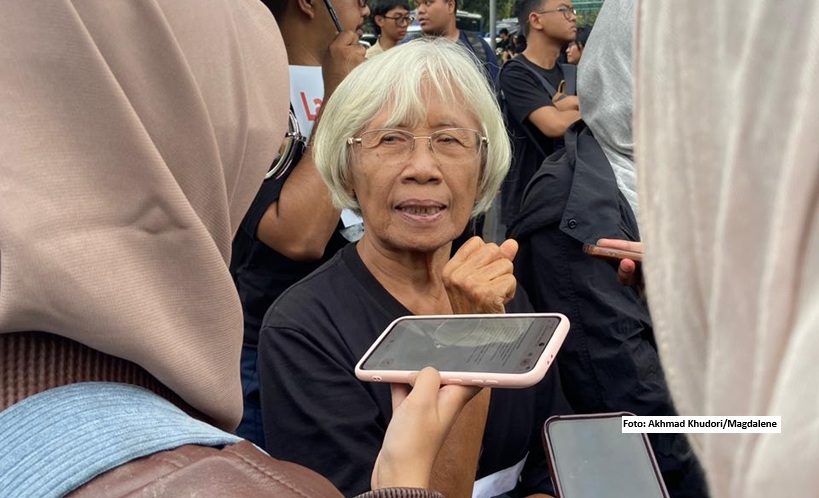

Community Legal Aid Institute’s (LBHM) Casework Coordinator, Yosua Octavian, expressed mixed emotion about Mary Jane’s Veloso’s transfer the Philippines. While he was glad to see progress in her case, he could not fully celebrate.

First, despite the Philippine Government abolishing the death penalty, the legacy of extrajudicial killings from former President Rodrigo Duterte’s “war on drugs” remains a serious concern. Veloso’s safety must not be overlooked. “We’ve handed her over to you (the Philippine Government). Make sure she stays alive and safe there,” Yosua said at LBHM’s South Jakarta office on Friday (20/12).

Second, Yosua, could not help but think of his client, Merri Utami, who has a similar case but remains imprisoned with little progress from the Indonesian Government.

In 2001, Merri, an Indonesian migrant worker, was dubbed the “Heroin Queen” by the media after being caught at Soekarno-Hatta Airport with 1.1 kilograms of heroin. Before her flight, she had received a bag from friends of her ex-boyfriend, Jerry, whom she had met in Taiwan. Like Veloso, Merri had no idea the bag contained drugs.

In 2002, an Indonesian court sentenced her to death. She narrowly escaped execution in 2016 when the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) postponed it due to certain considerations. That same year, LBHM began assisting Merri’s daughter, Devita Christa, and has since provided ongoing legal support.

Although her clemency was approved in 2023, Merri remains behind bars at the Semarang Women’s Correctional Institution (Lapas) Class 2A in Central Java, waiting for her freedom.

Yosua recounted his September 2024 visit to Merri after completing another case in Cilacap, Central Java. “I went to see her with a heavy heart because I didn’t have any good news to share,” he said.

While Merri appeared composed, her prolonged detention has taken a psychological toll. She initially enjoyed meeting new roommates but found it heartbreaking when they left. Many completed their sentences and said goodbye, while Merri could only watch them go.

“She’s been there for over 20 years, while most detainees stay for just one to three years,” Jojo explained. “A sentence like 20 years, life, or death makes you feel like you’re an irredeemable sinner in the eyes of the nation.”

Yosua added, “Merri claims she’s fine, but when her roommate says, ‘Merri, my sentence is over. I’m going home,’ she wonders, ‘Everyone’s going home. When will it be my turn?’”

Also read: Research Finds Most Death Penalty Convicts in Indonesia Still Denied Fair Trials

Victims of Criminalization

Wahyu Susilo, Executive Director of Migrant Care, shared an essay highlighting the vulnerability of women migrant workers being exploited as drug couriers by syndicates. Using Mary Jane Veloso’s case as an example, Wahyu emphasized the importance of applying non-punishment principles to human trafficking victims. Criminalizing drug couriers, he argued, is fundamentally unjust.

“These individuals,” Wahyu explained, “are victims of transnational organized crime.” He called for courts to adopt a more progressive approach toward couriers. Instead of imposing harsh sentences, justice systems should prioritize uncovering information about the main perpetrators and the broader network of operations. Unfortunately, this approach was absent in both Merri Utami’s and Veloso’s cases.

Harsh punishments for couriers, Wahyu noted, disrupt efforts to track the syndicates’ chain of command, ultimately allowing the true criminals to evade accountability.

“Criminalizing drug couriers who are genuine victims of trafficking syndicates—especially sentencing them to death—is a grave injustice,” Wahyu concluded. “It perpetuates the opaqueness of syndicates that are intricately linked to human trafficking operations.”