Media, State, Public, and Sex Crimes

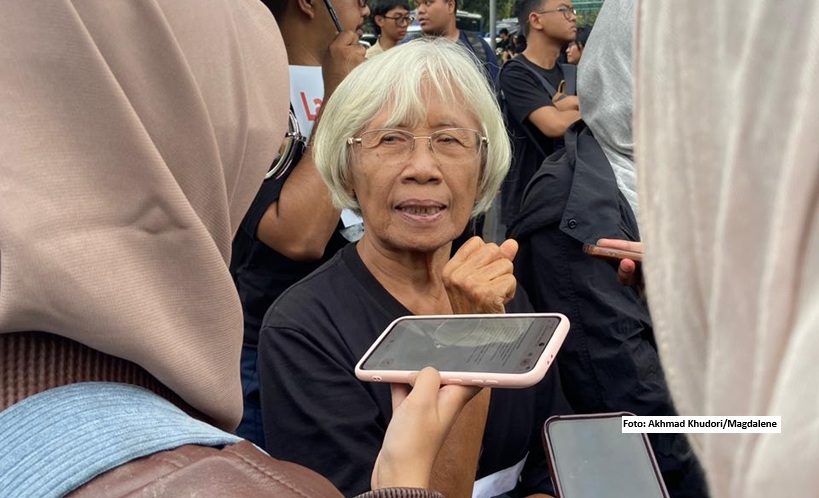

It was a campaign driven by sincerity, tenacity, and outrage. Kate Walton, a Jakarta-based Australian feminist activist, read about the gang rape and murder of a teenage girl in rural Bengkulu, often regarded as the backwater part of Sumatera. Upset that the crime only made regional news, she reached out to fellow feminists in Indonesia and overseas.

For most Indonesians it was another unimportant piece of news. The crime did not happen in urban Java, and rapes and murders were typical news stories. For Walton, the location did not matter and the crime demanded deeper scrutiny.

A girl had been brutally raped and murdered, and she deserved justice. After getting details on the story, several people I follow online said they were so sickened and they wondered why there was no outrage like in India four years ago.

Back then the Indians reacted strongly to the murder of a university student who was attacked and gang raped in New Delhi on her way home from watching a movie in a mall. The world took notice as thousands took to the street (and violent clashes with riot police ensued) and English-speaking Indians worldwide shared their thoughts online.

It was a stark contrast to a crime that would happen a few years later in a forgotten place in a non-English speaking country.

After a week, however, the Indonesian feminists’ social media campaign began to show some results. Walton’s contacts agreed to write the story for international publications, and some celebrities and public commentators amplified the case by informing their followers what had happened in Bengkulu. Then national newspapers and television stations followed up, one month later.

Now Indonesia has known the story of Y, and the response is predictable. Alcohol and pornography are both blamed for influencing the men and boys who raped and killed her, since it’s revealed that they often hung out to drink moonshine and watched porn videos through mobile phones. To prevent other sex crimes, ban alcohol and blame pornography, so the arguments go.

On the other hand, several feminists have appeared on television to Parliament to pass the long overdue anti-sexual violence bill and to explain the true nature of rape.

Sex crimes became a nationwide topic in May, replacing the Jakarta Bay reclamation controversy, and run alongside the communism controversy. But while being thankful that the weeklong online activism had shined a light on Y and rape culture in Indonesia, we have also seen the ugly reality of how Indonesians view sexual violence.

Indonesians condemn the rapists and killers, and then support death penalty and state-sanctioned castration for future sex offenders. That is not what feminists want – we want imprisonment and rehabilitation. We want tougher and more comprehensive laws against all forms of sexual violence, not just rape. We want better sex education at schools and home.

Even among us, there are debates: should we reveal her name in media reports and in our campaigns? Is chemical castration ethical, especially if a convicted sex offender agrees to take it? Is sex offender registration effective?

Should we resign to the fact that concepts like consent, marital rape, and rape culture are still not universally accepted even in the West? Or should we push our government and judicial system to do better?

Meanwhile, news on sadistic rape and murder appear every day, many of them happened in and around Jakarta. I interpret three possibilities on the increase of rape and murder news this month. The most optimistic interpretation is that the press and public are more aware of sex crimes.

The gloomier interpretation follows what happened in India a few years ago – the outrage after the New Delhi case was followed by other high profile rape cases, including ones targeting foreign tourists. The constant buzz instead led to copycat crimes, as gangs of men watching stories on rape wanted to rape, regardless of what would happen afterward.

The worst interpretation is that media corporations race to find and present the most dreadful rape cases, for hits/viewers and profit. Rape and sexual assault stories are popular not out of social awareness, but out of voyeurism. Thus we cringe and condemn several websites and newspapers for running stories with grotesque headlines and descriptions, without any regard for the victim and her family.

A voyage into the social media shows that the public is no better than the media. Victim blaming is rampant, although fortunately, there is always someone who will challenge the victim blamer.

Young men use the “nature of male” argument, while young women use the “don’t ask for it” argument to blame victims of rape. At the same time, it is also disheartening to read people casually advocating death penalty and physical castration without any desire to discuss the nature of sex crimes.

The rapists and killers of Y were sentenced to 10 years after an express trial, but I was seriously disturbed when seeing the news. All suspects wore balaclava mask and many could not walk with two feet. There are rumors that the police put the masks (including boys accused of raping a girl in Surabaya) on suspects to hide the traces of beating by the officers – not out of rage but for entertainment.

Therefore there is a discussion that sex crimes in Indonesia will remain endemic due to toxic masculinity and the culture of violence including among the law enforcement. This week The Economist condemns virginity test (paywall) in the Indonesian armed forces in an editorial – which any Indonesian general can retort lazily along the lines of “We’re not a Western society. We’re a Pancasila society”.

Challenges against virginity test will be perceived by the military as an insult against them, just like any discussion of 1965 and of Marxism do. Meanwhile, religious reason will stay as the biggest stumbling block for serious sex education in Indonesia.

While Indonesians are still years away from understanding sexual crimes, the conversations are already taking place in the region, sadly as high profile violence against women have taken place in Seoul and Tokyo. As for the media, the hope is that there would be better journalists and editors.

Check out Mario’s take on Asian women and unrealistic body image and follow @mariorustan.

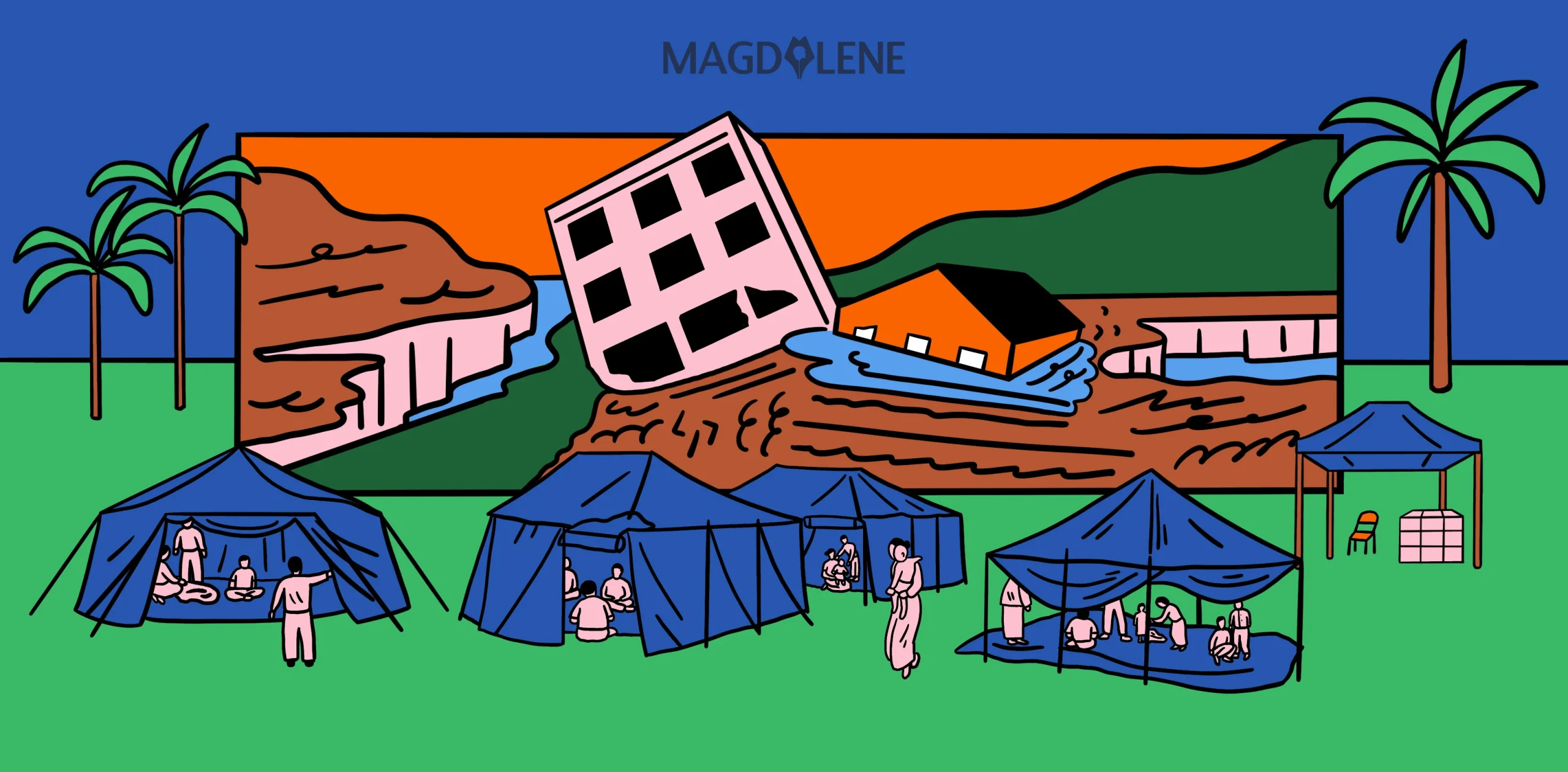

*Illustration by Faris Abulkhair