Muslim and Minority: Shias’ Struggle in Indonesia

As an adherent of Shia Islam in a mainly Sunni nation, university student S, 26, has learned to be discreet about her faith throughout her young life. Her parents are Shias – her father converted a while back after reading the book Shia: Rationalism in Islam written by Muslim scholar Abubakar Atjeh.

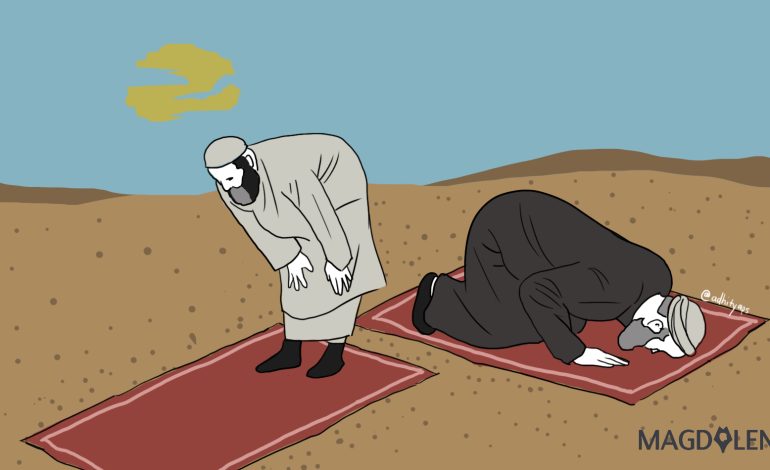

The Shi’ite prayers are performed slightly differently than the Sunni prayers. It became a problem when she was still in school. At final exams of religious subject in school, she had to perform the prayer the Sunni way.

“I felt awkward every time I took the test. Although I had learned how to perform the Sunni prayer before the exam, my memory failed me, because there are some differences between the Sunni and Shia prayers.”

These differences would draw the reaction of her religious teacher, who would accuse her of rarely praying, although she wore the Islamic head covering.

“In high school, I told them that I prayed differently, because I came from a different sect. My teacher said, ‘There is only one Kaaba and there is only one Islam. How can you say that you are different? I don’t understand it,’” she recounted her teacher scolding her.

Over time she learned to keep her faith to her self, like most Shias in Indonesia.

“Shia Muslims who work at office usually perform Sunni prayers just so they won’t be asked questions by other people. We are tired of having to answer these questions and, ultimately, to explain the theological aspects of our belief.”

Having to explain themselves is probably the least worrisome aspect of living as Shias in Indonesia. Across the country, the Shias have been robbed of their right to practice their religion openly and freely.

In 2012 the East Java chapter of the Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI) issued an anti Shia-fatwa, calling it a deviant sect in Islam. In the same year Shias in Sampang were driven out of their hometown – their leader Tajul Muluk was charged for blasphemy and sentenced to two years in prison. Two years later hardline Muslim groups established the National Anti-Shia Alliance (ANNAS). West Java’s Bogor Mayor Bima Arya recently banned the celebration of Shi’ite religious festival, Ashura.

Though not a new phenomenon, anti-Shia sentiment in Indonesia has risen in intensity in recent years. The sentiment began after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which, though inspired hopes for change, triggered the government’s suspicion.

Ahmad Hidayat, the Secretary General of Shia organization Ahlulbait Indonesia (ABI), was a university student at that time and he recalled the political situation in Indonesia after the Iranian revolution: “At the time, almost all Islamic activists in Indonesia glorified Ayatollah Khomeini, because Iranian revolution was considered as an open door for the awakening of Muslims world after its previous decline.”

But Hidayat believed that then President Soeharto was forced by Saudi Arabia and the United States to curb Shi’ite movement to prevent revolution. He also believed that Soeharto urged MUI to issue a fatwa warning Muslims about “the dangers” of Shia. Still, the negative sentiment wasn’t nearly as strong as it is today.

“I personally declare myself as Shi’i in 1987. At the time I expressed my religious thoughts openly and I didn’t have any problem, although there had been seminars in which Shia was deemed a heresy,” said Hidayat.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, hatred of Shia wasn’t as high as today, he said. But the fall of the Soeharto regime after the Reforms movement of 1998 also led to the strengthening of religious hardline movements.

“Some suspect that the current anti-Shia campaign is funded by Saudi Arabia and Qatar,” he said.

One of the issues raised by the anti-Shia movement is the threat of a Khomeini-style revolution, an accusation that Hidayat dismissed as “ahistorical.”

“Except in Iran, there has never been a revolution staged by the Shias. In Iraq, when Saddam Hussein was in power, many Shi’ite clerics were persecuted. But they realized that waging a revolution could put their country at high risk. And in Iran, the revolution was a response of people’s discontentment with Reza Pahlevi’s pro-Western and pro US policy,” he said.

Citing the Shia-based Hezbollah as the most powerful political movement in Lebanon, Hidayat said: “If the Hezbollah wanted to take over the country, they would be able to do it. But they don’t have any intention to do it. They respect the power-sharing consensus.”

The consensus is that the president of Lebanon must be a Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim, and the Speaker of Parliament a Shi’i Muslim, he said.

“In Indonesia, we also respect a consensus, which is the state ideology Pancasila and the constitution. I am a Shi’i Muslim – I was born, live, and will die in this country. That’s why I am obliged to respect the consensus of this country,” he said.

He said aside from the fact that the Shias population is very small in Indonesia, it also believes that the universal values of Islam are aligned with the national philosophy of Pancasila. The five principles of Pancasila are the belief in one God, just and fair humanity, unity of the nation, government led by the people’s consensus, and social justice for all citizens.

Hidayat said that in the past two years groups claiming to be “humanitarian organizations” have been using the Syrian war to raise money for the Syrian people. Many of them discredit Shias by spreading lies that the Shias are killing Sunni.

“Since Bashar Al Assad won the 2014 presidential election, false news suggesting there were massacres of the Sunnis by the Shias have constantly been spread,” he said. He pointed out that in the same year the National Anti Shia Alliance (ANNAS) was declared.

“The anti-Shia movement was established ‘by design.’ The more they spread hatred, the more they earn money,” said Hidayat.

Being stigmatized as a deviant sect is not easy, but ABI makes sure it does not get provoked by the negative sentiment. Most people in Indonesia disagree with the intolerance group, he said, though, unfortunately, they are a silent majority. To protect the Shia community ABI allies itself with various non-governmental organizations in Indonesia, including the Ahmadiis, another persecuted religious minority group in the country.

“In Jakarta, we established alliance with 47 NGOs. With the Ahmadi community, we filed for judicial review of the Blasphemy Law. In April 2016, we held a focus group discussion to talk about MUI’S plan to issue fatwa against deviant sects,” said Hidayat.

The Shias should keep educating the public and telling the truth, although it won’t be easy, because the extremist groups are the enemy of civilization, he said. Countering negative campaign through the media is an important aspect of this effort. Websites offering information on Shia helps to dispel the toxic lies spewed on the internet by some hardline Islamic websites.

For people like S, simply making friends with the right people help to counter the stigma and make living as a Shi’i much easier. After graduating from high school, S, who works part time at non-profit organization, said she fared better at university, because she befriended people from various backgrounds.

“I have close friends who are Ahmadi, Catholic and atheist,” she said, adding that if the two Shi’ite organizations ABI and Ikatan Jamaah Ahlulbait Indonesia can unite, it can resolve the problems affecting Shia Muslims, and even help protect other religious minorities.

Read Wulan’s story about how refugee girls find fulfillment through futsal.