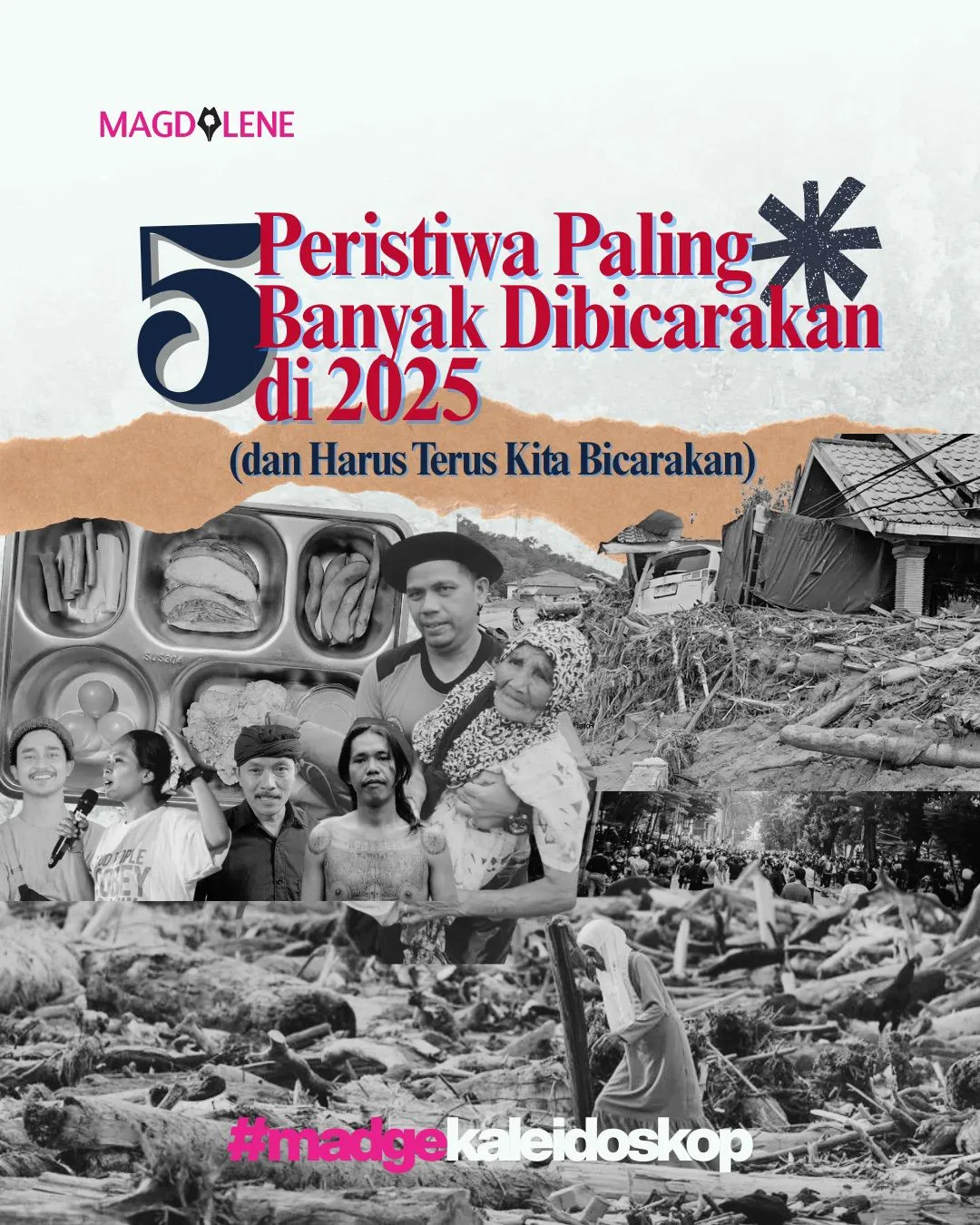

Every time I hear the phrase bencana alam, especially in the wake of the catastrophic floods and landslides in Sumatra, I get uneasy. Not because the government refuses to declare it a national disaster, even as the death toll climbs past a thousand. But because the term itself masks something deeper: power.

We use bencana alam, or “natural disaster”, so casually that we forget how language is never neutral. As argued by scholars like Norman Fairclough and Michel Foucault, language reflects and reproduces power. The way we describe disasters says a lot about who gets blamed, and who gets away.

That is why bencana alam matters. It doesn’t merely describe what happened. It frames what happened, and what we should do about it.

In Indonesian public life, we have seen how power shapes vocabulary and makes certain terms socially acceptable while others remain marginal. One obvious example is how gendered language circulates more easily when it supports dominant norms. The same mechanism appears in other domains, including technology. Ideas that seem futuristic, like robots designed to carry pregnancy or be sexualized, do not arrive from nowhere. They also reflect who holds influence and what priorities are normalized in male-dominated fields.

These examples differ, but the pattern is similar: when a society’s dominant groups shape the “common sense” of language, certain perspectives become default. Others are pushed aside, treated as oversensitive, political, or simply irrelevant.

Also read: Sedia ‘Aku’ Sebelum Hujan: Membaca Idgitaf dari Banjir Bekasi

How words shape what we see and what we ignore

The phrase bencana alam is so widely used that its formation is rarely questioned. Linguistically, bencana alam is a compound noun: bencana (disaster) as the core, and alam (nature) as the modifier. The result is compact and convenient: an unfortunate, harmful event caused by nature.

That convenience is precisely the point. The phrase positions nature as the main actor. Nature “does” the disaster. Humans appear, at most, as victims responding after the fact. This might seem harmless as everyday language, until we notice how often disasters today are entangled with human choices and human systems.

Even an etymological guess about when the phrase became common cannot fully explain why it became dominant. To understand that dominance, it helps to borrow an idea from Nirwan Dewanto’s essay “Menuju Hukum Alam” (Towards the Law of Nature), which reflects on the relationship between nature and civilization. Nirwan points out how humans have long seen themselves as subjects and nature as an object—something to be controlled, labeled, and extracted from. But nature is not a passive backdrop. It responds, resists, and sometimes strikes back.

Science once “corrected” the human belief that the sun revolved around the Earth. In similar fashion, nature corrects our flawed assumptions—through extreme weather, rising seas, and yes, floods that carry uprooted trees into camera view.

Still, we call it bencana alam. We silence the evidence of human contribution.

Also read: 72 Jam Tanpa Suara: Diamnya Pejabat Perburuk Penanganan Banjir Sumatera

Language as a shield

Humans describe nature through language. We produce sounds, words, and sentences that create shared meaning and shared intention. This is where power enters again. For Fairclough, discourse is never just about communication; it is also about social control and legitimacy. For Foucault, knowledge and power are intertwined—what a society treats as “true” or “normal” often benefits particular arrangements of authority.

Through repeated use, a phrase like bencana alam can become part of common sense. It begins to feel like the only available description. And once a phrase becomes common sense, it becomes difficult to challenge without appearing disruptive.

That is why the phrase can function as a hedge. It is “safe” because it protects humans, especially powerful ones, from uncomfortable questions. It provides a convenient shield each time a disaster occurs: it buries human involvement and blurs responsibility. If the disaster is “natural,” then it is tragic but not political. It is unfortunate but not accountable. It calls for sympathy and donations, perhaps, but not necessarily for scrutiny of policy, corporate practice, or long-term exploitation of land and resources.

This essay is not an attempt to launch a campaign to ban the words “natural disaster.” The point is simpler: to encourage a pause. To notice that the phrase is not innocent, and to recognize what it makes easy to ignore.

Once we see that, the question becomes less about vocabulary and more about position. Do we want to keep speaking in ways that protect power and erase human responsibility? Or do we want language that helps us hear nature’s “voice” and confront what human systems have done to amplify harm?

Wulandari Pratiwi is an independent linguistics researcher. She has been writing and presenting research at international linguistics conferences since 2013. She holds a master’s degree in English Education. Her articles have been published in The Jakarta Post and Magdalene.co, and her children’s books have received awards from Indonesia’s Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education and the Ministry of Finance.