The Biogas Darling: Turning Trash into Fuel

Deep in the narrow alley of West Java, inside one of southern Bandung’s densely inhabited slums, it was not difficult to find Dewi Kusmianti’s house. Mention the key words “My Darling” and locals would nod and point you to the right direction.

Deep in the narrow alley of West Java, inside one of southern Bandung’s densely inhabited slums, it was not difficult to find Dewi Kusmianti’s house. Mention the key words “My Darling” and locals would nod and point you to the right direction.

It is short for “Masyarakat Sadar Lingkungan” (Environmentally Conscious Community), a group Dewi founded to take care of the garbage in the neighborhood inhabited by about 1,000 families.

“People found ‘Masyarakat Sadar Lingkungan’ too mouthful and they kept forgetting our name. So, inspired by a Hindi song with the verse ‘Oh, my darling, I love you’, I shortened our name to My Darling. It worked!” said the 39 years old mother of three.

The name quickly caught on, becoming a term of endearment for Dewi and her troop of 38 passionate people, mostly housewives who have helped turning mountains of filthy, mismanaged household trash into handicrafts, composts, organic fertilizer and biogas. The playful nickname, however, masked the years of struggle and despair only strong and tenacious people like Dewi could survive, though in her case not necessarily unscathed.

Long before she became the trash warrior, Dewi and husband Tonton Pariyono, 41, worked at a garment factory in Cijerah, Bandung. When the Asian monetary crisis hit, the company went bankrupt in 1999 and they were laid off along with hundreds of other employees. Dewi worked at another factory in Jakarta afterward, but lost the job in less than a year when the company also folded.

With Indonesia being hardest hit by the prolonged crisis and equipped with only a high school diploma, the couple could not find another job. Their severance pay quickly ran out, and having sold all their belongings, the family found themselves on the street, living hand to mouth from busking at traffic lights.

In 2003, in a moment of desperation from being homeless with three sick children, Dewi wrote about the family’s ordeal for a readers’ column in a local newspaper, Pikiran Rakyat. The paper’s columnist sympathized with her and rented a room for the family in Cibangkong area, where they continue to live until now.

Four years later Tonton found a job as a garbage man, collecting the neighborhood trash to be dumped at a nearby landfill. Every night he came home exhausted, complaining about headaches after spending the whole day with rubbish. Curious, Dewi took a trip to the dumpster and was shocked to find mountains of trash filing up the 200 square-meter space.

“It wasn’t just the smell. When I got closer to the garbage, I also felt an intense heat like standing in front of a stove. No wonder my husband felt sick,” she said.

“There was so much waste that I was afraid of my husband’s safety. He could have easily trapped under a trash avalanche and die.”

Unraveling the Problem

After poking around, she realized the complexity of the problem. It was a vicious cycle. Some residents didn’t want to pay the trash collection fee of only Rp 2.000 (20 US cents), thinking that garbage was supposedly taken care of by the government; some paid but the money seemed lost somewhere. Meanwhile, the local sanitation office refused to handle the waste if they didn’t receive any payment.

Dewi began to look for information on how to manage garbage. Later on, when the dumpster manager gave up and quit his job, she proposed to take over the management of the garbage. The community unit head welcomed the idea during a meeting, but local figures were hostile toward her.

“This particularly powerful man, whom everybody feared, pointed at my face and yelled at me, ‘How on earth can a woman possibly handle this problem? Even men have failed’,” she recalled.

“I was furious but I swallowed my anger and I told him ‘Insya Allah (God willing), I can do it, Pak’.”

She knocked on all the doors in the neighborhood, asking residents to sort out their trash.

“People complained how smelly the trash was but didn’t do anything. I said, ‘Let’s clean it up. Don’t blame the government…. let’s do something about it’,” she said.

Coordinated by My Darling, eventually the residents were willing to pay the fee, so the sanitation office returned to pick up the trash. With the group of 12 housewives, she sorted out the trash, sold some and recycled some of the remaining into handicraft products. The amount of trash gradually became more manageable.

In 2009, the group signed up for ‘Bandung Green and Clean’ competition. Although they didn’t win, it attracted the media and a non-governmental organization, which provided some funds for their program and taught them to make compost.

But composting was too high maintenance, and with the neighborhood located on the bank of an often-flooded creek, which would ruin the composting material, it did not make much economic sense (the compost sells at a mere 5 US cent a kilogram). Their other program, the trash bank, which bought recyclable garbage from people, left them broke.

An NGO called Yayasan Saung Kadeudeuh later sent a biogas researcher to the area, and helped find a donor to help build a machine to convert trash into biogas. The methane gas resulted from the process is channeled into the nearest household and used for cooking.

So far, only a few houses received the biogas because of the limited outreach. But the recipients said it helped them a great deal in cutting household expenses.

“We usually bought four 3kg LPG gas canisters a month, each costing Rp 17,000. But with the biogas, we barely need a canister a month. And we only have to pay Rp 10,000 monthly for the biogas,” said a resident named Dono.

Dewi hoped there would be enough funding so that the entire area could receive biogas, especially since the LPG price has soared recently to over Rp 100,000 for a 12-kilogram canister.

Foul Play

Thanks to My Darling, the trash in her RW 11 community unit in Cibangkong area is much more manageable now. In contrast with landfills in other neighborhood, theirs looks like a proper warehouse with roof, accommodating neat stacks of garbage, recycled goods, composter and biogas converter.

Dewi has also expanded the program to another community unit, so six biogas converters are now available in two RWs. To encourage people to continue sorting their trash, Dewi gave out small plants she planted herself on the side of the river. She also put up photos of people who help the program on the communal notification board, and encouraged people to create biopores, to reduce puddles and flood when it rains.

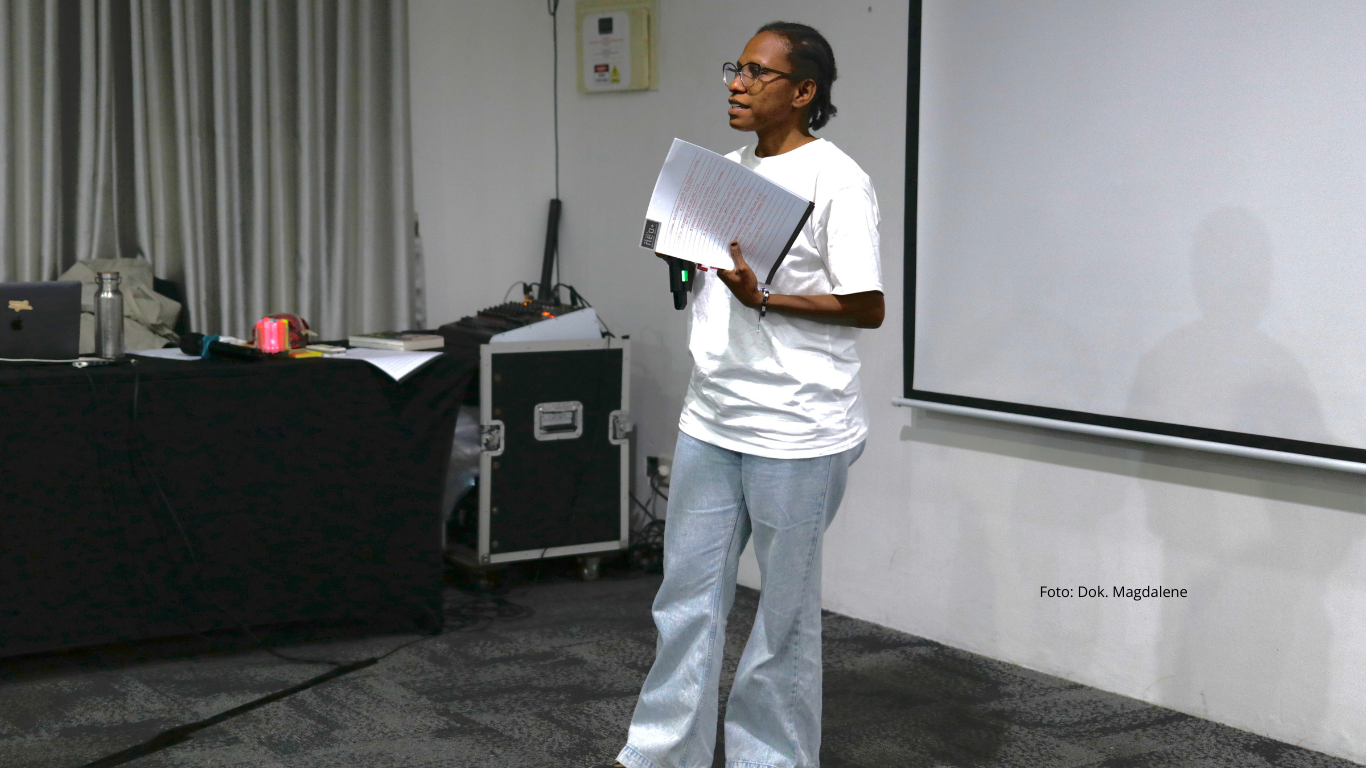

Once a week, she gathers the women in her community unit to teach them skills like cooking, recycling, or doing presentation.

Despite her valiant efforts, a number of neighbors, the so-called respected figures are not happy to see the recognition she has gotten from the media, NGOs and the government. They were particularly unhappy when a popular TV program last year interviewed her, and pledged to give her Rp 50 million in donation, a cardboard version of which she was shown on TV to have received.

“Some people were really angry, they came to my house, accusing me of taking all the credit and of embezzling the money. I’m not a soft-spoken woman, who can just keep my mouth shut, so I asked them, where were they when I asked for their help. One of them punched me in the face,” she said. The intimidation continued, with the rest of the community were too afraid to back her.

In the end, she never received the donation after she and the RW head failed to make a proposal to meet the donor’s request.

“I’m only a high school graduate, I don’t know a thing about writing a proposal. Pak RW got upset and said, maybe it wasn’t just our destiny to get the money. So, we gave up. We told the TV station that we just didn’t know what to make the proposal so we might as well turn down the money. I think the TV station was upset,” she said.

As far as the money goes, she swore to have never taken a penny of any donation for herself.

“I’m a religious woman, I’m afraid God will be angry with me if I use the money,” said Dewi, who wears a headdress.

The trash business had come with a price for her family, she said. She could no longer work to earn a living, although she does earn some money when she is invited occasionally to speak about her program or to train other communities.

The tiny modest brick house with cement floor that she shares with another family is frequently inundated. Her husband earns Rp 500,000 a month as a garbage man, while each of the children has problems of their own. Her eldest has diabetes, her middle child is autistic, and the youngest suffered from brain aneurysm.

“What I really want is a job with steady paycheck. But I can’t ask the donors to pay me, that would be wrong, and besides they always emphasize that the donation is for the community,” Dewi said.

As for the community, she wants it be sustainable.

“I wanted to use the donation to establish a business for locals here, so our economy would improve.”