Where Hospital is Not an Option – Giving Birth in Remote Rural Indonesia

A woman lies on her side on a trolley in the delivery room, and her legs keep twitching with nervousness. Three hours into labour, “Mina” (not her real name) is only 3 centimeters dilated. Largely unable to speak due to a speech impediment, she indicates constantly that she can’t stand the pain. The midwives stroke her shoulder gently and tell her that she is strong.

I’d like to call what Mina was lying on a “bed”, but that would be too generous a name. Just a thin foam mattress separates her body from the steel frame of the trolley, itself no wider than the woman’s hips. A thin curtain separates her from the rest of the room, where people wander in and out, seemingly at random. There is little pain relief available, and certainly no epidural. There is also no doctor.

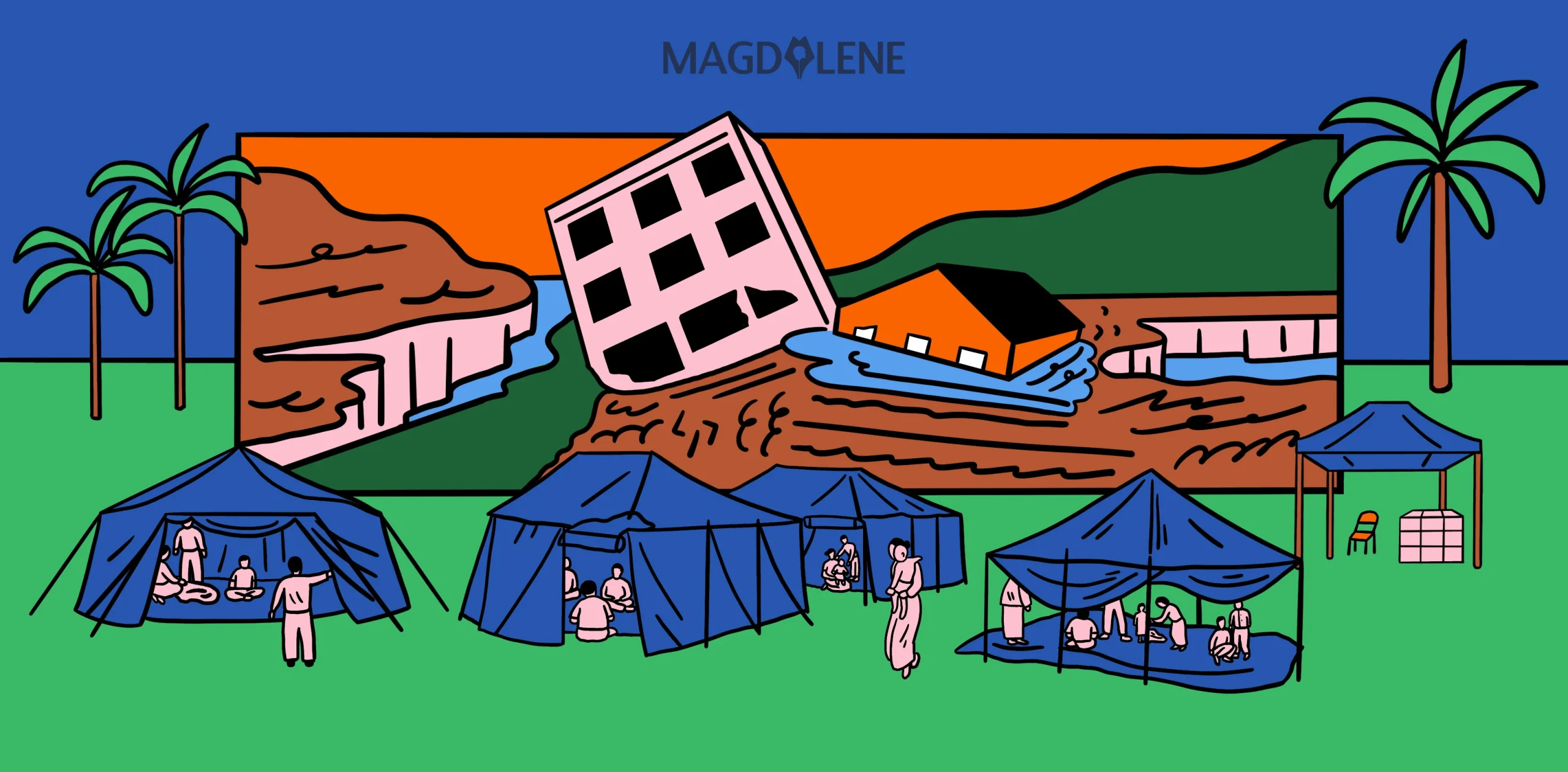

Mina is 38 and pregnant with her fifth child. Here in a remote district surrounded by palm oil plantations in inland West Kalimantan, Indonesia, pregnancy can be life threatening. Like the other women in the village, Mina had only the local government community health clinic, or Puskesmas, to turn to when it came time to deliver her baby.

Compared to many other villages, however, Mina and her family are lucky. They happen to live in a village with the big Puskesmas, which has an emergency room where people can stay overnight. All of the other 16 villages in the subdistrict must rely on smaller, less-prepared clinics in their own villages, or travel for up to an hour by motorbike over roads made of little more than red dirt and rocks to reach the main Puskesmas. Hospital is not an option for any of these women – the “nearest” hospital is two hours away, simply too far away to be reached in time.

For a while, it looked as though Indonesia might get close to achieving its target for Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5 on maternal health. The country’s maternal mortality ratio (MMR) hovered at 228 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2007, and had been decreasing since the early 1990s, when it had been as high as 421/100,000. MDG 5 states that Indonesia should achieve a ratio of 102 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2015. So in late 2013, Indonesia’s health workers were shocked when the 2012 Indonesian Demographic and Health Survey indicated that the nation’s MMR had actually increased by over 50 percent, to a staggering 359/100,000.

The trend reversal has left the development circle searching for answers. The increase in deaths could not be blamed on a low level of skilled health workers attending births – this had risen to over 80 percent in 2012, from just 32 percent in 1991. Nor can the reason be the lack of antenatal checkups, of which 93 percent of Indonesian women receive at least one of the recommended four.

So what is killing Indonesian mothers? The Indonesian Ministry of Health states that hemorrhage after labour is the biggest cause of death, with eclampsia (seizures due to high blood pressure) coming a close second. Both problems are incredibly hard to handle, even for trained midwives. Both can be caused by pre-existing health issues, such as anaemia (lack of iron) in the case of hemorrhage and hypertension in the case of eclampsia. Both anemia and hypertension are found at extremely high rates among Indonesian women, around 65 percent and 30 percent respectively, with many more cases believed to be undetected.

One of the major underlying issues is that of nutrition. Poor families tend to prioritize fathers and children when portioning out food, and many people are unaware that pregnant and lactating women require even more food than normal. Even when eating adequately sized portions, Indonesian women tend to consume more carbohydrates (rice) and salt than recommended, and far less fruit, vegetables and red meat than needed. Usually this is due to a combination of lack of awareness about proper nutrition, lack of access to a variety of foods and poverty. Indonesian health workers are recommended to provide 90 iron tablets to all pregnant women for the course of their pregnancy, but it is reported that only one-third of women receive the full 90 tablets.

Mina is most likely one of these women. The midwife tells me her hemoglobin is only 6. Hemoglobin is the iron-containing molecule than transports oxygen in red blood cells. A level of 6 is extremely low and considered critical. In a big hospital, Mina would probably have received a blood transfusion by now. Here, in far inland West Kalimantan, the local clinic is her best chance at survival.

This article was originally published in Kate Walton’s blog.

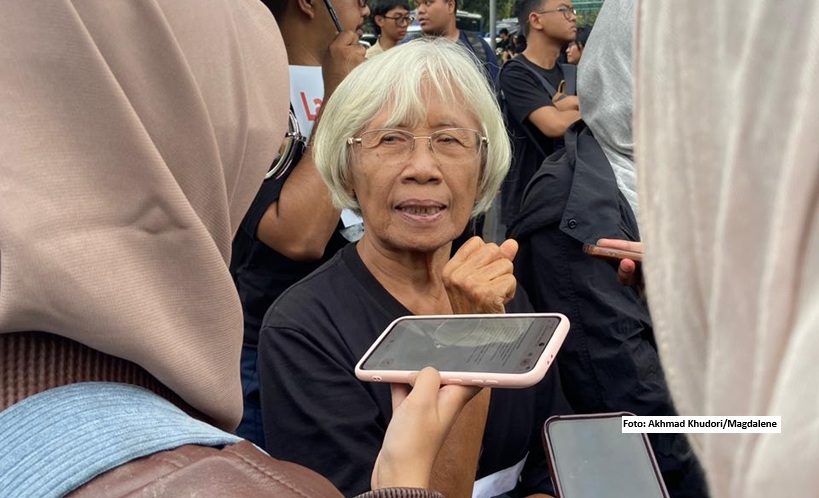

Kate Walton is a queer feminist activist, writer, and photographer. She works in maternal health and is passionate about women’s rights. Outside of work, she loves cooking Indian food, drinking tea, and trying to read more books than she did last year.