Why Sex Education Matters

I’ll be talking about sex, so let’s get the sexy words out of the way first, shall we?

Periods, wet dreams, clitoris, testicles, blow jobs, cunnilingus, orgasm, anal sex, condoms, IUD, gonorrhea, vibrators, HIV/AIDS, sexual abuse, respect.

That wasn’t so hard, right? It wasn’t too awkward either, I hope. Did you know what they all mean, though? No?

In this information age, you would think it would be easy to look on the Internet for accurate information on sex and our bodies. But information overload sometimes makes it harder to find quality information. Try google the words I mentioned above and you’d probably find a lot of porn. If you managed to ignore the porn, then you’d most likely be presented with a boring WebMD page or a blog by a dubious self-styled sex expert.

Finding accurate information is hard, which is why the recent rejection by the Supreme Court of a petition by the Indonesian Planned Parenthood Association (PKBI) to include an article in the 2003 National Education System Law stipulating compulsory sex education is that much more disappointing.

The court argued that sex education could be integrated in several school subjects, such as sports, biology, religion and counseling. I have to disagree, mostly because I think that if sex education got integrated into other subjects, students would treat it only as materials to memorize for an exam, not the vital information that they would need the future.

Sex education is important not only to teach the younger generations about sex and their bodies, but it also teaches respect for each other, encourages sex-positivity and also builds rapport between students and adults, namely their teachers.

Discussing sex in Indonesia is taboo, but it is never really clear why. The majority believes that discussing sex in a Muslim-majority country is wrong, because it might encourage our youth to have pre-marital sex, which is forbidden according to some religious perspectives.

That being said, you would be wrong if you said that Islam, a religion followed by more than 80 percent of the population, was not sex-positive. Of course it is! How can you argue otherwise when, in Islam, a wife can legitimately divorce her husband if he can not sexually satisfy her? If that’s not sex-positivity, then I don’t know what is. But I’m getting way ahead of myself.

Many argue that since sex is a private matter, it should only be discussed within the realms of one’s family, as each family has a different set of values and morals based on their religion – or lack thereof. But how can you say it is a private matter, when UNAIDS reported that around 660,000 people are living with HIV nationwide and 34,000 people died of the related disease in 2014?

Parents are also not omnipotent. Sure, you can argue that parents should research as much as they can about , so that they can explain it well to their children when the latter ask of it – and I agree! Parents should prepare themselves – but no amount of information-scouring – most likely on the Internet — will make parents as eloquent as a trained reproductive health educator or a counselor, who is used to dealing with youth problems. Furthermore, parents from the lower economic background may not even have access to such information. And even if they did, they may not have time to go to the local community health center to ask about such things.

But wouldn’t it be awkward to talk about sex in class? Sure, initially it might, but I think that says more about the adults than it does the children. On the contrary, sex education can build trust between children and adults because it is such an intimate topic. Speaking about this in class signals students that you will help them without judging them, if they have a problem or a question, whether or not sex-related. They won’t be afraid to ask questions to adults and would less likely go on the Internet or rely on friends, whose accuracy can be questionable at times, for information on sex.

As mentioned above, sex education can also yield to a more sex-positive generation. This means that we must encourage youths not to see sex as “wrong”, because if we do so then – once again – they’ll seek out other sources. Being sex positive does not mean that we encourage them to have pre-marital sex, but to do it safely if they choose to and that is a move that will protect generations to come. I mean, ask yourself now: do you know how to put a condom on? Do you know where to get a pap smear? Do you know how sexually transmitted diseases spread?

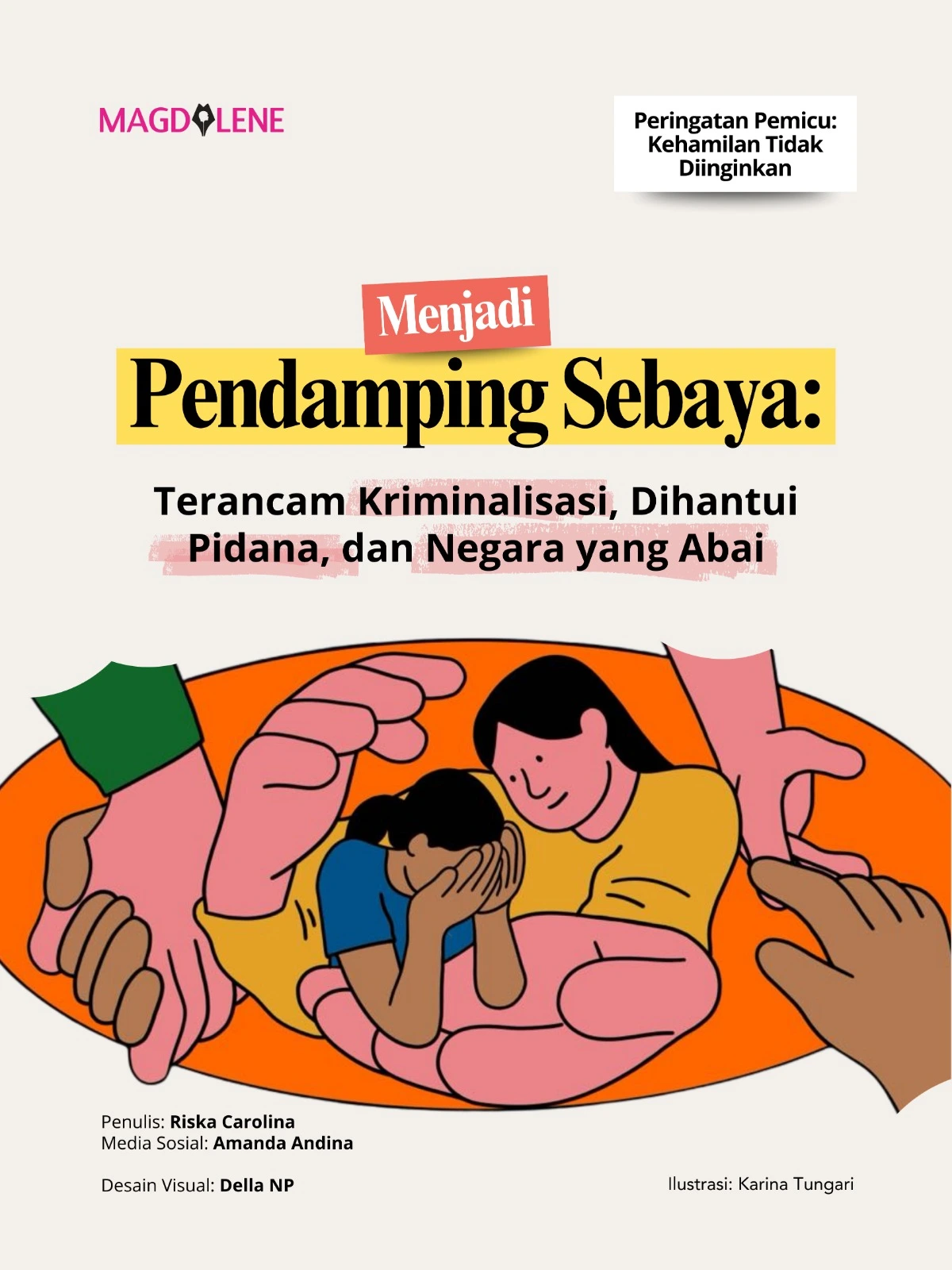

Ultimately, sex education is not just about teaching youth about their reproductive systems, different sexualities and how to have safe sex. Proper sex education will also teach them how to respect each other and to identify signs of sexual abuse, an important issue in the light of the Indonesian Child Protection Commission’s (KPAI) finding that 50 percent of cases of violence against children in the country involved sexual violence.

Sex education can also spill over to other issues, such as our horrendous maternal mortality rate (MMR), which has actually risen in the past decade. If our youth received sex education, they would understand that girls’ bodies do not stop developing until their mid-twenties and it is dangerous for them to get pregnant young. It may one day lead to a change in our 1974 Marriage Law which allows girl as young as 16 to marry.

Sex may be a tricky subject but it doesn’t have to be a mystery. Whether or not you do it, sex is a part of life, and not discussing won’t make it go away.

*Read Fedina’s piece on Niki Minaj.

Fedina S. Sundaryani is a budding journalist who has travelled all her life and who wishes to settle down and find some place called home. She graduated from Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University in the tiny city of Beppu, Japan, with a degree in the ambiguously named Asia Pacific Studies. Her interests include side-eyeing meninists, reading and watching makeup videos on YouTube.