Women Weavers Struggle to Produce and Market Tenun

“My grandmother taught me how to weave back when I was 15 and I’ve been weaving ever since,” said 47-year-old Marselina Masi from Lembata, East Nusa Tenggara, when I met her recently. A single mother – her farmer husband died 15 years ago – weaving tenun has enabled her to feed her family and pay for her children’s schooling.

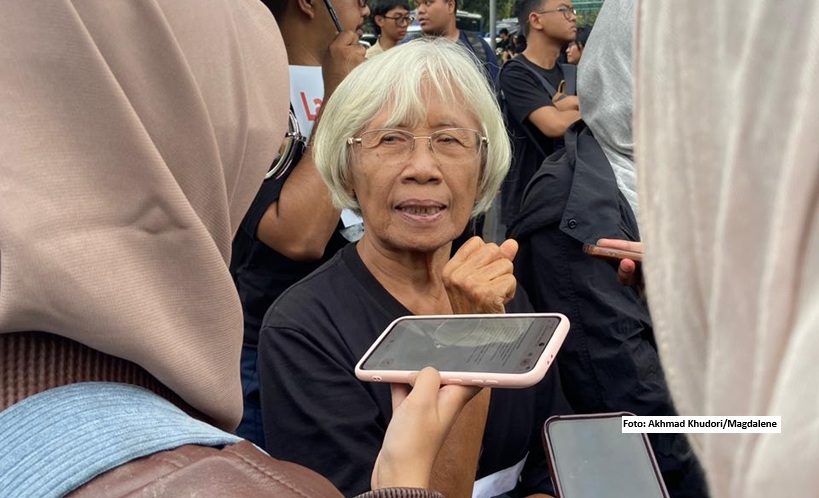

Mama Marselina, as she is affectionately called, was in Jakarta last weekend along with several other women from Lembata for the tenun exhibition “Sole Oha” in Textile Museum, Jakarta. The exhibition was organized by the organization of women breadwinners PEKKA (Women-Headed Families Empowerment) and social enterprise Torajamelo, which have been working together to support women weavers in some areas in Indonesia.

Out of some 30,000 women involved in PEKKA, 5,000 are weavers. The month-long “Sole Oha” exhibition at Textile Museum is aimed to showcase the women’s work as well as to raise awareness on their struggle. The exhibition is participated by women from Adonara and Lembata, East Nusa Tenggara, as well as those from Toraja, South Sulawesi, and Mamasa, West Sulawesi. For many of them, this was the first time they ever set foot in Java.

“Behind every strand of fabric is a woman’s life that we must protect,” Torajamelo’s founder Dinny Jusuf said.

“We aim to preserve tenun and also to rejuvenate it, so that women weavers can sell their products to broader customers. We do this because we see the gap between the heritage and todays’ market. People merely see tenun as a traditional artifact, a thing they buy just once for keeping, but not for wearing. Yes, we understand the need to keep tenun in its original form, but we also realize that if we want to keep tenun alive, we have to make it ‘wearable’ for daily uses,” she added.

In East Nusa Tenggara, tenun is used in sacred ceremonies like weddings and funerals.

The craft requires a high level of precision, and those who buy tenun sarong for rituals expect nothing less than a flawless product.

“The buyers would bring rulers with them. They check whether the lines are absolutely neat and straight. If it’s slanted, even just a little, the weaver will have to redo everything until it’s perfect,” said Agnes Sai, 68, who, like Marselina, sells tenun at a local market in Lembata.

It usually takes about a month for experienced weavers like Marselina and Agnes to finish a sarong. Because of its cultural value and the precise way it is crafted, a piece of woven sarong for rituals is valued at Rp 8 million to 17 million. But a meter-long headscarf to be worn daily usually sells for about Rp 200,000 a piece. These, Agnes said would only take several hours to make. Currently they rely on foreign tourists, who mostly come to the area during the local harvest festival month in August

.jpeg)

But producing a piece of woven fabric is a time-consuming process. While rolling a cotton thread, Marselina explained to me the lengthy process from harvested cotton to the actual finished product.

“I harvest the cotton every two years,” she said. “Yes, two years! The rain doesn’t come very often. So we would just stock them up, bit by bit. Once we finally have enough, we start to turn them into threads, color them with mengkudu or tarum, and then eventually weave them,” she said.

It then takes another two years for the color to turn the way it should be, she added.

Using store-bought threads just won’t do, the women said. “The colors wash off too easily when we weave them and wash them,” said Marselina.

Torajamelo provides alternative threads for women weavers and introduce new schemes of colors so that their tenun fabrics can catch up with fashion trend. Marselina and Agnes expressed their approval of the Torajamelo threads, saying the material is good and the colors don’t wear off during the weaving process.

Much-Needed Support

Dinny called on the government to provide support to the weavers, one of them is by ensuring domestic supplies of cotton.

“Indonesia’s national production of cotton is zero. We have the tradition of weaving, we have the weavers, but we don’t support them enough to help them to profit and live well from what they can do,” Dinny said.

“This is really heartbreaking. In order to mass produce, we have to import the cotton. Importing cotton makes the production cost so high, so the weavers gain minimum profit as they have to make the products affordable for their buyers. Weavers from China or Thailand can get access to good cottons because they produce it nationally. They don’t need to import. Here, women weavers are left out to compete with the global market,” she added.

Susana Rawa Borot from PEKKA said there had been some efforts made by the authorities to encourage people to wear tenun.

“Though there are still challenges, we also notice some progress. For instance, recently issued regional bylaws encourage all teachers, men and women, in Flores to wear tenun sarong on Monday. This might sound simple, but if people start to wear it more regularly, they would likely buy tenun from the local weavers more regularly too,” said Susana.

PEKKA supports and empowers women breadwinners, those who are not married, or who are widowed or divorced, or whose husbands don’t provide for the family. Other than providing the threads, PEKKA also builds their capacity, such as giving book-keeping training, so that the women can manage their finances .

Another important part in the effort to support the weavers is documenting the whole experiences, struggles and attempts to preserve tenun. The Biru Terong Initiatives (BTI) aims to promote the cause to the public by producing documentary films of women weavers.

“We don’t have good national archives that pay enough attention to this heritage. We don’t want our next generation to know nothing about tenun. It should be our mission to preserve the culture as well as to educate more people about it,” said Vivian Idris from BTI.

*The Sole Oha exhibition will be held until December 17, 2017, but the women weavers will only be there until December 3.

Follow these five body positive Instagram accounts.