You’re Free to Love Your Country the Way You Like It

Once upon a time, I described nationalism as my main political identity. Once upon a time, I loved Indonesia with all my heart. The Indonesia I loved was utopian. It was an Indonesia imagined, not experienced.

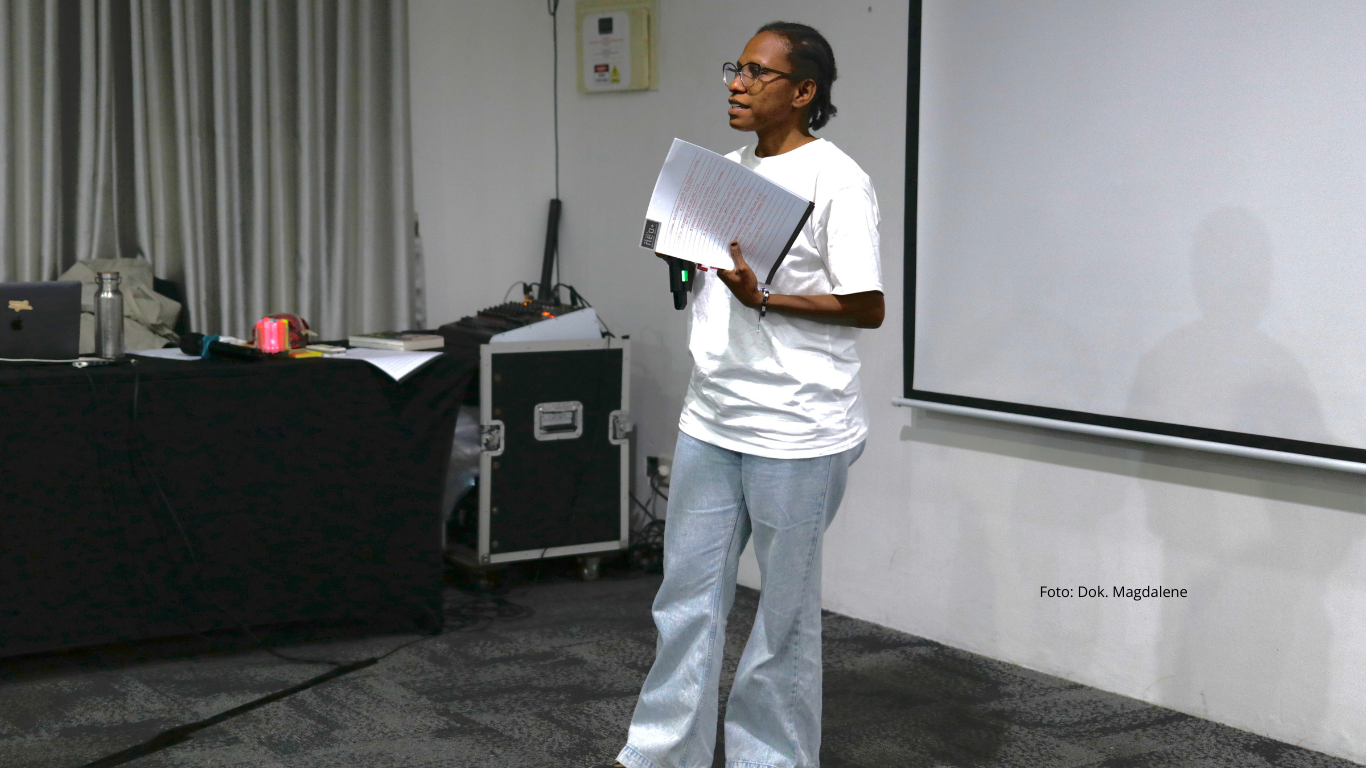

In the Reformasi years (from 1998 to probably 2004), all the topics forbidden under the New Order came unbound. Frans Magnis Suseno published his introduction to Karl Marx. Several translated books on socialism, printed by small-scale publishers in Yogyakarta and Jakarta, found their way into Gramedia and Gunung Agung book stores, competing with Robert Kiyosaki and Khalil Gibran books. The short stories of Seno Gumira Ajidarma and the late Y.B. Mangunwijaya showcased the stories of ordinary Jakartans and Yogyakartans throughout the New Order and the dawn of Reformasi.

It was also a time when Elex Media published the Indonesian edition of several Taiwanese and Malaysian books on Chinese culture and history. I read them while watching Metro Xin Wen and listening to Taiwanese pop albums, legally available for the first time in decades. I believed that finally Chinese-Indonesians could express their culture and racial identity freely, just like Chinese-Malaysians did.

It is easy to love your country when you’re overseas. It’s because you represent your people, at least in campus or workplace. You’re “the Indonesian”, and there are not many Indonesians overseas compared to Filipinos, Thais and Vietnamese. When you meet other Indonesians, you might feel the warmth of cooking soto (Indonesian soup) together and joking in Indonesian dialects, talking about Indonesian politics and celebrity gossip, and sharing tips on little-known shops and service. You might meet Indonesians from places and backgrounds you never imagine. The descendant of a royal Moluccan family. The gay Acehnese. The former urban guerrilla turned florist.

Meanwhile, the well-ordered system in your host country might make you more optimistic about Indonesia. Yes, bicycle lane is possible in Indonesia. Yes, a profitable cooperative is possible in Indonesia. Yes, a well-written, well-drawn animated franchise is possible in Indonesia. You have seen how very qualified Indonesians distinguished themselves in projects and competitions.

I lived that good life, the good life of jogging through chilly park while listening to Sheila on 7 mp3s. The good life of reading Kumpulan Cerpen Kompas (Kompas Short Stories Anthology) on the bus. The good life of dining with Indonesian academics and artists residing in Australia, and with celebrities and politicians visiting from Jakarta. I befriended Muslim Indonesians from Bandung, and traded ghost stories from our secondary schools.

I took classes on nationalism, from the 19th century romantic nationalism in Europe to the independence movements in Asia. I proudly talked about being a Chinese-Indonesian to Australian students, many of them children of immigrants. I read Jean Gelman Taylor’s Indonesia: People and Histories, which discusses the archipelago as a world of nomads, travelers, missionaries, and jagos. In her thesis, jagos – thugs – always dictate Indonesian politics, from Ken Arok to the VOC to New Order’s militia terrorizing Jakarta and Dili. I, however, believed that corruption, thuggery, and militarism were the past, and Indonesia was on its way to catching up with Malaysia and Thailand.

Returning to Indonesia, I realized that nothing really changed. The streets were still crammed and dusty. The malls still provided a refuge for the middle class and the rich from poverty and pollution outside. The jagos were still dictating Indonesian politics. The Reformasi had expired.

Like in Australia, I failed to connect with the Chinese-Indonesian community, even online. On the other hand, the religious and racial walls were there again – Christian Chinese-Indonesians led different lives to Muslim Sundanese and Javanese. To this day I regret my decision to come home.

Had I lived in Australia, I would experience a more severe nationalism crisis. Australian lefts condemn public holidays such as Australia Day, ANZAC Day, and Queen’s Birthday, which in their view celebrate colonialism, racism, and imperialism. White supremacy finds its way into mainstream media. Mark Latham, a former opposition leader, has become a men’s rights activist. While conservatives say that African gangs have wrecked Melbourne, feminists point out that dozens of women have been murdered by men they know.

Feminists in Asia have more complex relations with nationalism than white feminists. In Asia, nationalism defeated colonialism. Like in my experience, nationalism helps Asian expatriates in the West be proud of their background. But nationalism is defined by patriarchy, even more than in the West. Patriarchal nationalists deny that the LGBT+ communities and independent women are part of the “Eastern culture”, not merely Western import. These days several governments in Asia demand women to get married and give birth, while tolerating homophobic religious groups.

Compared to other Asian nationalities, we find it harder to leave Indonesia for good, and we don’t know why. We can only say because Indonesian food is unbeatable, or because our family is here. I aspire to migrate, knowing that there are other cultures and societies that align with my values and habits better. On the other hand, I have friends who pick Jakarta over North America or Singapore, and are firm with their decision. I also know Australians and Europeans who are happy to live here.

We are living in a time when hostile nationalism is spreading like virus. We are also living in a time when it’s easier than ever to live overseas. We wish that eventually we are free to live where we want to, and that more people can love their country while being honest about its history – and working out on how to build a more just and fairer future for all.

Whether you’re thinking about leaving Indonesia, or coming back to Indonesia, or staying in Indonesia, you can do good for Indonesia with your own way, with your own vision. There is no perfect country, but there is a home you can find.

Find out about why some Indonesian Christians support Donald Trump and follow @MarioRustan on Twitter.