Wanted: Film Classification Board, Not Censorship

Indonesian moviegoers, even the most apolitical ones who don’t follow the news, would likely know the name of the chairperson of the country’s Film Censorship Board (LSF) by heart. Right before every movie, local or foreign, is screened at a cinema, the person’s name is displayed for a good several seconds to show the film has been certified by the censorship board.

A remnant of the Dutch colonial rule and the New Order regime, with their tight grips over every aspect of society, LSF has for decades continued to be a powerful body that decides what the public can watch. The board holds the power to review and censor films, television drama (known locally as sinetron) and pre-recorded talk shows, as well as commercials, before they can be released to public.

Many people, especially filmmakers, think the existence of the censorship board is no longer required in a democratic country where freedom of expression should be upheld. The board is the government’s way to control public consumption. Moreover, it is seen as obsolete amid the widespread distribution of audiovisual products through various channels.

“Censorship is no longer relevant today,” said filmmaker Joko Anwar.”People should have the ability to filter what they want to see, especially for underage family members. Censorship doesn’t empower people to do so,”

“An institution with such absurd mandate is therefore no longer needed. It is not just redundant, but its function is no longer relevant,” he reiterated.

Im 20017 a group of filmmakers have tried to disband the board by filing a judicial review against Film Law No. 8/1992 on the basis that the articles on censorship violated the 1945 Constitution, particularly on freedom of expression. The move was made shortly after LSF passed Ekskul, a film that stole music scores of foreign films which then went on to win the Citra Award, the country’s Oscar, leading to boycott and protests from filmmakers. The legal attempt was rejected by the Constitutional Court.

Far from being weakened, the House of Representatives passed a new film regulation, Law No. 33/2009, that reconfirms the existence of LSF. Its role is strengthened by Presidential Regulation No. 18/2014 on Film Censorship Board, which stipulates that LSF has the authority to open branch offices in provincial capitals.

Films as National Security Issue

The 2009 law raised some questions, chief among them is its opening statement that states that film is an aspect of national security, a chilly reminder of the continuing influence of the authoritarian regime at play. As an artistic and cultural work, the law saya, film “has a strategic role in improving the nation’s cultural security and people’s welfare both material and immaterial, to strengthen the national security.”

This is the reason behind placing LSF under the oversight of House Commission I on defense, foreign affairs, communication and informatics, and intelligence. The Commission selects and appoints members of the censorship board. When it comes to budget, however, the board works with House Commission X overseeing culture, but reports to the President through the Ministry of Education and Culture.

To this day LSF’s 17 members comprise representatives of the military and police. Ironically

only two people in the board represent film sector. The current chairman is Ahmad Yani Basuki, a retired major general who server as special staff to former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

“(LSF has members with military and police background) because there are films related to wars,” Yani said in an interview with Magdalene at his office. “Secondly, films are related to security, cultural security, in fact, which is an aspect of national security. Foreign movies, especially, are not always in line with our culture. If all cultures are eroded by foreign culture, our national security could be undermined.”

Before the 2009 law, Yani said, LSF comprised representatives of government ministries and agencies, and civil society institutions. Yani served as a representative of the Indonesian Military (TNI) for LSF. After the 2009 law is in place, the members consist of 12 community representatives and five government elements from the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Ministry of Religious Affairs, the Ministry of Tourism, the Ministry of Communication and Informatics, and the Creative Economy Agency.

The 12 community representatives must have competence in film, culture, law, information technology, security and safety, language, religion “and/or other relevant expertise”.

“We are publicly selected by the committee established by the Cultural Ministry, and the members have to go through a fit and proper test at House Commission I,” said Yani.

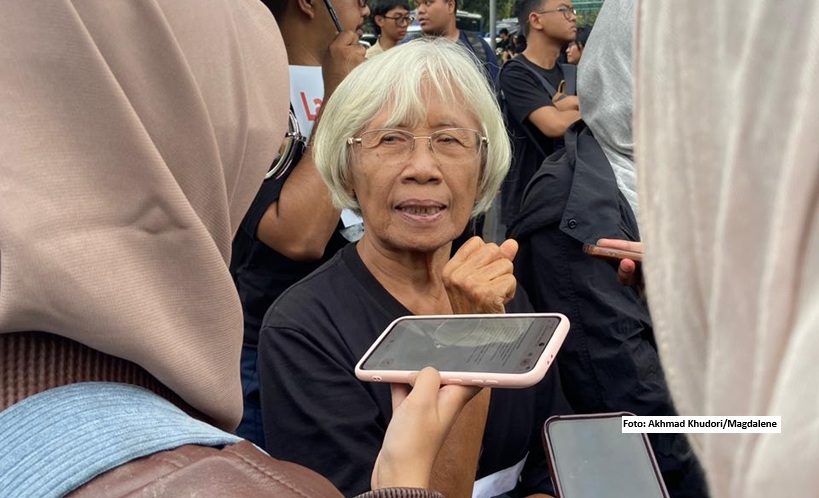

Film archivist and critic Lisabona Rahman said the fact that LSF is selected and overseen by House Commission I shows the state’s assumption that filmmaking is a dangerous activity with crime potential, instead of an act of creativity.

“That’s the thing about censorship. The basis is the suspicion that there is something bad or evil in film or any other art. The censorship board is defining and thinking what is considered bad and evil, and deleting the parts that they think are bad and evil. It should be the job of police and the court. A civilian institution should have concentrated on good things that need to be shared and enjoyed collectively,” Lisabona said.

“But the point is we should agree on the basic assumption that film can be valuable, fun and sometimes provide useful lessons.”

Legislator Irene Roba from House Commission X said that since LSF reports to the Cultural Ministry, it makes more sense for the board to be Commission X’s counterpart.

“But of course there are other considerations to make if we want to shift the partnership of LSF from Commission I to Commission X,” she told Magdalene.

Unclear standards, indicators

The road to getting a film passed by the censorship body starts with registering film title to the Ministry of Culture’s Film Development Center (Pusbang Film). If it is not made into film within a certain period of time, the title can be used by other people. Once the film is completed, it has to be submitted to LSF that scrutinizes all elements of the film from the theme to plot and pictures.

“We want to make sure that the plot is understandable, to ensure that it has educational value. Even if it is of comedy genre, it should be decent. It must not have scenes where teachers or elderlies are being slapped in the head by younger people, it’s impolite,” said Yani.

According to the 2009 Film Law, films must not contain elements that:

- Inspire the public to conduct violence, gamble, and use drugs;

- Show pornography;

- Provoke conflicts between groups, ethnicity and races;

- Blaspheme, insult, and/or tarnish religious values;

- Encourage the public to do illegal act; and or

- Degrade human dignity

LSF’s 17 members are assisted by 33-strong staff in doing their job. Yani said the censorship does not take long: it targets to issue a censorship certification and age classification for a film in one to three days. For a feature film, the body will charge Rp 1,000 per minute, for a commercial video Rp 5,000 per minute, and for information/documentary/education film Rp 250 a minute.

“If necessary, we would invite experts to discuss about the issues in the films,” Yani said.

He said there has been progress since the 2009 law was passed, because LSF no longer just cut the film but instead return it to the filmmakers with notes on the parts that must be censored.

“If the filmmakers object them, they can appeal and we can have a dialog. Usually they question the age classification,” Yani said.

While filmmakers praised the dialog mechanism, they questioned the standardization and rationales of the censorship and age classification.

Director Kamila Andini of Sekala Niskala (The Seen and Unseen) recalled how the body decided her film did not require any censorship, but still classified it for viewers over 14 years old.

“They said the film is too heavy for children. It’s as if children under 14 years old are presumed unable to absorb a slow and dark plot,” Kamila told Magdalene, adding, “‘heavy’ is subjective.”

Joko Anwar said LSF wanted him to cut the murder scene of a family during dinner in his 2009 film Pintu Terlarang (Forbidden Door) claiming that it was like a manual for murder.

“I responded that the scene is not an invitation for murder, but it’s the ultimate consequence of a man who have been abused since he was a child. So I said it was an example for people not to turn into an abuser,” he said.

“We filmmakers have to provide very normative arguments to them,” he added.

LSF asked Joko to cut a scene from the same film in which a man rapes his wife, saying that it was a bad example and “there is no such thing as husbands raping wives because it is the wives’ obligation to serve their husband sexually.”

“Some scenes were cut, but then LSF slapped ‘Over 21 years old’ classification for the film, which is weird, because people over 21 years old should have been able to think for themselves when watching movies (instead of being censored),” Joko said.

Classification, not censorship

LSF members are selected every four years, which means the current members’ term ends this year. The 2009 Film Law stipulates that members can serve for two periods, but several existing members have been serving longer, from before the law was passed. Yani was the military representative before becoming a member and now chairman, and previous chairman Muchlis PaEni is still a member.

Beyond the organizational reform, many urged the government to shift LSF’s function to classification and education board.

Leni Lolang from the Indonesian Film Board (BPI), which serves and organizes filmmakers including for film festivals, said with so many festivals both in the country and overseas, it is not only impractical but also impossible to impose censorship.

“There are so many local festivals now, small ones, and they can screen any film. LSF wants to censor the films screened in these festivals as well as those that are going to be screened in overseas festival,” Leni told Magdalene.

Hilmar Farid, the Ministry of Education and Culture’s Director General of Culture, said with so many film platforms beyond the cinema, it is impossible for LSF to cover them all and censor the content.

“The role should be shifted from filtering what people should watch to empowering people with education so that people have self-mechanism to filter them,” he said in an interview with Magdalene.

“In the past two years LSF has done so, educating audience on film classification through schools and campuses,” he added.

Lisabona Rahman said what the country needs is an institution that can recommend good films and classify films according to cognitive development based on age.

“There should not be one measurement for good films, it can be an aggregation of several measurements like what Germany does through its institution, the Deutsche Film- und Medienbewertung (FBW),” she said.

FBW is a German federal authority for evaluating and rating film and media. It renders an expert opinion on films and its two certification marks for outstanding quality are “worthwhile” and “especially worthwhile”.

“So far, I don’t see LSF’s works in censoring films as transparent. Compare it to the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) that has clear and transparent classification and standards that reflect people’s current views and expectations,” Lisabona said.

Kamila said that apart from classification and rating, LSF as a state institution can defend filmmakers amid public attack amid the increasingly conservative society.

“Public censorship is actually more frightening for me — even a small public opinion affects a film. LSF has actually done this well once when the children’s film Naura dan Genk Juara (Naura and the Champion Gang) was accused of insulting Islam and was boycotted by a number of Muslim groups. LSF then issued a statement that the film does not blaspheme the religion, and the content has been approved by the state,” she said.

“The most important thing for me is an institution that sees eye to eye with filmmakers to work together to build Indonesian cinema that is democratic, open, diverse and contextual.”

Magdalene’s reporter Elma Adisya contributed to this story.

Illustration by Adhitya Pattisahusiwa