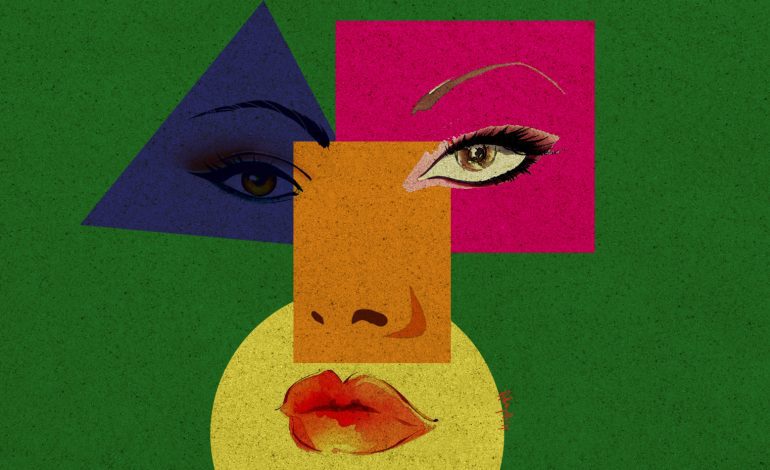

I am a Feminist, I Stand Against ‘Everyone is Beautiful’ Narrative

As feminists, we must have once or twice encountered a dilemma when approaching beauty issues. Feminism ideally wants to champion inclusivity and choices, embracing all types of women regardless of identity and looks. Various efforts have been made on this front, from promoting more diverse beauty standard, criticizing mass media, to coming up with “everyone is beautiful” campaign.

I’ve finally come to the conclusion, that the populist “everyone is beautiful” campaign is a problematic strategy.

To some extents, I understand the virtue of that narrative, which intends to tell women to be appreciative of themselves regardless of their body shape and looks, and to encompass all women outside the mainstream beauty standard. That remark comes to prominence as a response to relativism and shield against snobbery. We want to say everyone can have different taste and no taste is more superior than others. It implies a fear of being rude or mean to others.

However, the phrase implies that no one is ever really more beautiful or uglier than others. This is odd. While we insist on telling everyone is beautiful, we never say everyone is smart/kind/humorous/good at sex, although those particular traits may be desirable as well. The reason is we are well aware that some people just don’t happen to have those traits, and empowerment comes exactly when you are relatively different compared to anyone else.

This invites some questions: why? Why do we approach beauty differently? Why is feeling beautiful mandatory? Does thinking otherwise make women less meaningful and not worth loving?

Let’s leave this campaign. First off, I find it serve confusing goals. The sentence itself contains self-contradiction: if everyone is beautiful, then no one is. Instead, you end up normalizing beauty, because that trait is something everyone has. If we all have it, it becomes something common and redundant. But this backlashes, because people don’t say it to be useless or redundant. We say it to make us feel good, and, being naturally compelled to compare ourselves, we only feel good about being called beautiful because the meaning of beauty acts as a differentiator, not a common characteristic. No, realistically speaking, we all can’t be above average.

Put semantics aside, if you want people to feel good by convincing themselves they are inherently beautiful, that narrative is still problematic, because it tries to internalize that everyone must feel beautiful, as if beauty constitutes a universal standard of goodness everyone has to strive for. This amounts to putting too much value on beauty, indicating ugly or average-looking person is not valuable enough. It forces them to feel something they are aware they are not, when they are confirmed they are not pretty, while looking at their reflection in the mirror. This fails to empower women because it reinforces conventional idea of the importance of pursuing beauty, something that, unfortunately, not everyone has.

No wonder this approach is glorified in advertisements of women’s beauty products. That narrative translates into sanitized perpetuation of conventional norms of the importance of beauty, leading to falsehood that if you don’t feel beautiful, you must be miserable without any self-esteem. In that sense, not feeling beautiful is threatening.

It’s nice to be beautiful, but it’s not all what matters. Beauty should not be the paramount parameter in defining who we really are.

Secondly, this narrative at best can only work on individual level. Everyone by default has their own preferences, whether because we’re genetically wired that way or as a result of social construct. This collective subjectivity will transform into majority subjectivity, also known as societal beauty standard, and be exposed in mainstream media. The contestation of beauty, such as “white and skinny are pretty” or “beauty comes in various shapes and color” will lead to hegemonic beauty standard. While I do not agree with single-spectrum beauty standard, this “everyone is beautiful” is not helpful either, because at the end there must be certain criteria that have to be fulfilled to be aesthetically appealing in society’s eyes.

Thirdly, the alternate interpretation of this narrative – saying beauty goes beyond the extend of physical realm – is still problematic. It aims to tell you even though you are not physically beautiful, you can have inner beauty, compensating your lack of physical desirability. However, this can potentially polarize women by contesting the ones with physical beauty versus those with inner beauty, as if a woman with outward beauty is more shallow and superficial than one with inward beauty. It also ends up antagonizing women with physical beauty. Moreover, this interpretation still leaves us trapped with the obsession of finding beauty in everything.

In a nutshell, whether or not beauty is more than skin deep, the statement – and sentiment – that “everyone is beautiful” is nothing but a sugar-coated cliché.

But what alternative do we have?

We need to adopt a more realistic approach: promoting the idea of comparative advantage. Some are pretty, some are ugly, and that is perfectly fine. Some work their asses off and feel empowered by adhering to beauty standard. That is still fine, if and only if the choice comes informed, with a long assessment, and made by an autonomous woman.

Saying woman who succumbs to mainstream beauty standard is broken, colonized, and brainwashed is degrading and dictating them. We can’t simply ignore the existence of woman’s will and jump into that oversimplification. And for the ones who are not beautiful, they can thrive to be something else: intelligent, kind, hardworking, funny – any trait that also can make them outstanding despite not being physically desired.

It’s nice to be beautiful, but it’s not all what matters. Beauty should not be the paramount parameter in defining who we really are. Sometimes it’s just irrelevant. There are passionate, intelligent, conscientious, hardworking, kind and nurturing women. They may be plain ugly, but they are still valuable and respectable.

And watch your stance carefully: assess whether your decision to pursue beauty is because you seek blind validation and make your body a subject to overexploitation, or is it based on informed decision as an autonomous being.

This writing also acts as a reminder for me. Whenever I look at myself in the mirror and consider I am not beautiful, it does not negate the fact I’m still a worthy human being.

We don’t always have to be beautiful, sometimes we just have to be human.

Ellyaty Priyanka is a 19-year-old woman majoring in International Relations, Universitas Gadjah Mada. She is a cynical realist who is intrigued by the beauty of nothingness, paradoxes, and deep dark indie. Her best coping mechanism is either taking time and isolating herself from the world or comedying her own life tragedies along with her bitter friends. You can find her wandering around in her blog ellyatypriyanka.wordpress.com and Twitterland @amoreliaa.