Foreign Aid Drama: How Indonesia Might Be Blowing Its Climate Funding

Indonesia’s credibility as a responsible recipient of foreign aid is under threat. The recent controversy involving the Forest and Other Land Use (FOLU) Operation Management Office (OMO) at the Ministry of Forestry isn’t just about bad optics. It could seriously damage Indonesia’s standing in the global development community.

The scandal erupted when Minister Raja Juli Antoni appointed himself and 12 fellow Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI) members to key leadership roles in the OMO. His defense? Their salaries weren’t paid from the national budget (APBN), so there was no problem. But this reasoning sends the wrong message: foreign aid doesn’t deserve the same transparency and accountability as public funds. This is precisely the kind of logic that has fueled the global push to cut aid in recent years.

This isn’t just an internal ministry issue—it resonates far beyond Jakarta. It validates the arguments of foreign aid skeptics like Donald Trump and Elon Musk, who have long claimed that international assistance is misused or wasted. Trump’s dismantling of USAID—cutting 83 percent of its contracts and folding it into the U.S. State Department—was based on similar reasoning. That shift is still affecting global aid today.

The fallout? Developing countries like Indonesia are now feeling the strain. Aid for healthcare, climate funding, and democratic reforms has been shrinking under mounting political pressure. Trump’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO) was an early sign of this retrenchment. With European donors facing budget cuts due to the Ukraine war and domestic economic struggles, global aid is under pressure. Scandals like the OMO issue only reinforce the narrative that aid is mismanaged, making it even harder for developing countries to secure future funding.

Baca juga: COP29: Who Pays For Climate Action in Developing Nations Becomes More Urgent

When mismanaged aid hurts the most

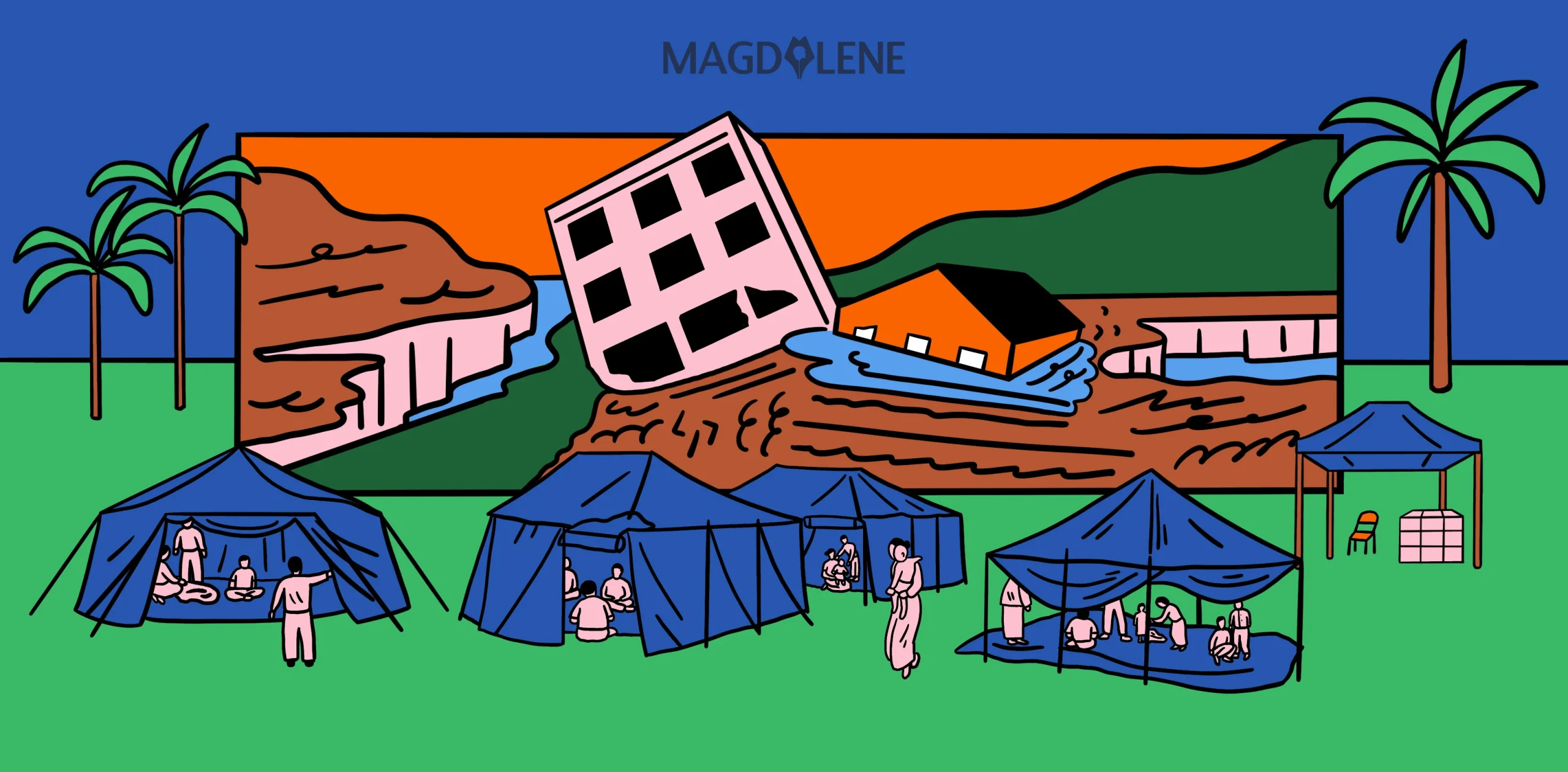

The consequences of mismanaged aid hit hardest at the grassroots level. Indigenous communities and women-led groups are at the forefront of forest protection and climate resilience in Indonesia. These groups rely on international funding for training, infrastructure, and capacity-building. When donor confidence erodes, these essential programs are the first to suffer.

Public frustration has already spilled onto social media. X user @BarengWarga urged Norway and the UK to pause their FOLU Net Sink 2030 initiative funding after the minister’s casual claim that the funds were “not from APBN.” Accusations of nepotism, lack of transparency, and possible misuse of donor funds have quickly gained traction.

Norway and the UK, however, have remained silent. The Norwegian Embassy has yet to comment, while the UK Embassy stated it’s a domestic issue. This silence reflects a broader problem in how international aid operates.

According to the 2005 Paris Declaration, donors agree to the principle of “recipient country ownership,” meaning that Indonesia decides how aid is used. However, this well-intentioned policy creates a power imbalance. Donors are expected to hold back even when apparent governance failures emerge.

Norway’s caution is understandable. In 2021, Indonesia abruptly terminated its climate partnership with Norway, only to resume it a year later. That rocky history likely explains why Norway is treading carefully now.

Baca juga: When Politicians Say Let’s Solve the Climate Change Problem, But They’re Not

Losing trust means losing influence

Donors and implementing agencies face a tricky balancing act. If they push too hard for reforms, they risk being accused of meddling in Indonesia’s domestic affairs. But if they remain silent, they allow taxpayer money to be spent without proper oversight.

That doesn’t mean donors are powerless. While they may not control day-to-day spending, they routinely conduct risk assessments to evaluate whether a country remains a reliable aid partner. These assessments help determine if funding should be maintained, delayed, or redirected elsewhere.

If Indonesia continues to mishandle foreign aid, donors will take action. Warnings often come in the form of risk assessments—early indicators that funding may be scaled back or rerouted. Governance issues, in particular, are a red flag.

Donors are unlikely to keep supporting Indonesia if it’s seen as unreliable. Instead, they will quietly shift their aid to countries they believe will manage it more responsibly. This isn’t a threat—it’s how aid works.

Baca juga: How Learning from Indigenous Communities May Help Save Our Climate

Foreign aid isn’t just about money; it’s about credibility. It signals diplomatic trust and, for many grassroots communities, it’s a lifeline. The more trust Indonesia loses, the weaker its influence on global platforms. And at a time when climate finance is shrinking, that trust is everything.

Losing it wouldn’t just cost money—it would sideline the very communities Indonesia claims to support, especially those already fighting to be heard.

Monica Kappiantari is a development practitioner with a background in both international development and a private sector. She has worked across sectors including climate, infrastructure, and governance, and is based in Jakarta.

Ilustrasi oleh Karina Tungari