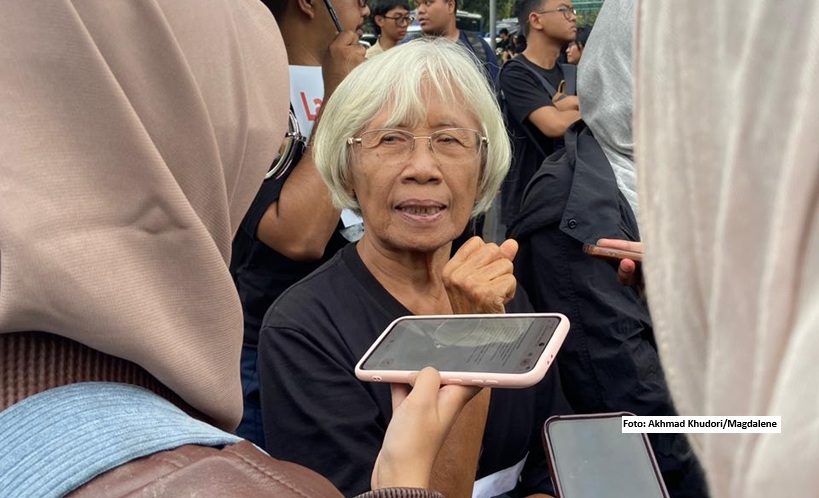

Luh Manis: Balinese Women Do So Much But Are Unseen

When I reached out to Balinese entrepreneur Luh Manis for an interview, she first invited me to join her on one of her “sisterhood retreats” to get an understanding of the work she does. Together with eight other Balinese women and another foreign woman we traveled to Kintamani, the mountainous area in Bali where Luh is originally from.

We spent a full day visiting temples, sleeping in a glamping site, practicing yoga, climbing a volcano at sunrise and going to a hot spring for bathing. Luh made us reflect on our lives in the women circle at night and we shared our life struggles and dreams for the future amongst each other.

Luh Manis, 38, founded her company Pranasanti in 2011, based on the Balinese philosophy of Tri Hita Karana, referring to the harmony among people, harmony with nature and harmony with God. Besides guiding retreats, she also conducts yoga classes and before the pandemic, she focused mainly on Western tourists coming to Bali.

She lives on her own in a cozy house at the end of an alley in the south of Ubud and welcomed me with tea and lots of fruits.

“My mother is worried that I live alone. She thinks it’s unsafe and she’d rather me to live with my brother. She used to ask me what’s wrong with me, emphasizing that most women in Bali get married before the age of thirty. I explained to her that not all marriages are beautiful. My mother works as a farmer and still lives happily with my father in the village where she was born,” Luh said.

At age 26 Luh was in a relationship but when she found out that her boyfriend was cheating on her, she broke up with him.

“On one hand I felt so sad and on the other hand, it was a reason for me to leave Bali, to go as far as I could because I had nothing to lose,” she said.

She’d always dreamed about snow and decided to go to Norway, where she experienced a totally distinct view on the position of women from the patriarchal society she grew up in.

“I saw that life was more liberal, women were able to make decisions about choosing their profession, getting married or traveling around the world and having children or not. It was ladies first and the men would even open the door for me. They would clean the house and they’d like to cook!” Luh said, laughing.

Also read: Balinese Writer on Theatre, Community and Decolonizing English Literature

Her travels impacted her life back on the island. During her journeying in Europe, she witnessed the urge for control and the constant stress of a modern lifestyle.

“It made me question what happiness is because these European women seemed to have everything and still they were tense and found it hard to relax. When I returned back home, it was as if there were two people in my body, one of them wanted to be in Europe and the other wanted to be in Bali. And I felt depressed because I couldn’t find happiness in either one of them,” she said.

Finding Her Calling

Before leaving to Europe Luh had studied tourism (“because that’s what you do here”, she says shrugging her shoulders) and worked different jobs in the hospitality business from a young age to provide for herself. And it was through reading autobiographies about mostly local women heroes that inspired her to follow her own interests.

Following the 2002 Bali bombings, Balinese psychologist professor Ni Luh Suryani was all over the news as she helped many people dealing with their trauma. This made Luh Manis realize that she too wanted to find work to support humanity.

“And I felt strongly that I wanted to focus on women because in my home village, the first priority has always been the men. It’s always men who decide on local bylaw, tradition, marriage, land, and social life. I don’t see many women involved in that process,” she said.

“We as women can do so much more if we get the right support. In Bali, most women end up with nothing after a divorce. That’s the reason I wanted to set up my own company with my own income and own a house.”

Also read: Singer Kai Mata: “I’m here to claim the space that is rightfully mine.”

Her friends often tell her how “revolutionary” she is, but Luh has always felt like an outsider. Even when she returned from Europe she wasn’t the more stylish, more modern woman people expected her to be after travelling abroad.

“People found me weird because I was depressed and confused. I expected that more money and a liberal life would bring more happiness but my soul didn’t feel happy at all,” she said.

Luh Manis (Illustration by: Kazuaki Senno)

She went to visit the high priest to check if her depression was caused by “black magic” and whether she should do a ceremony to remove it. The priest instead told her that she has a special gift, that she should follow the training to become a local priest, primarily for her own inner healing and to find her calling and purpose.

“I did fasting, water purification and strengthened my body through yoga and meditation.

Now, water purification has become a tourist attraction but for me at that time it was revelatory. I spent a lot of time in nature, going from one holy spring to the other and from one mountain to the other, all by myself,” she said.

As she shared some pictures on Facebook, people got interested to join her. She was already teaching yoga at that time, and more people, particularly tourists, booked her class. It was then that she realized it was a great way to earn a living.

Also read: For the Love of Ubud

Delving into Spiritual Community

Her business took off so successfully that she was booked two years in advance and hired ten employees. And then the pandemic came.

“I was home alone for a few months and so many local women asked me for emotional, financial and mental support. During the full moon in August (2020) I felt a strong calling to help the Balinese women. And because not everyone earns money during this crisis I decided to do some of my work based on donations,” Luh said.

Before the pandemic her work focused mostly on Western women, even though it took a while before she felt at ease in the so-called Ubud spiritual community.

“Most foreigners talk a lot about the beauty and culture of Bali but don’t always invest in good value to this island or hang out with the local community. They’re visiting cafes where only foreigners go and they’re networking among other expatriates,” she said,

“I actually felt stupid at first when I heard them talking about higher dimensions, auras and channeling energy. It made me feel like a stranger in my motherland,” Luh added.

When she saw a Western woman at a spiritual festival leading a Balinese ceremony in not exactly the proper way, she realized her responsibility to become more active in the spiritual community. Nowadays she combines the best of both worlds.

“I’m quite Westernized for Balinese standards, I’m not afraid to speak up, people might find me too wild, but I haven’t forgotten about my own family, my community and the ceremonies where we connect with our ancestors. I think it’s important to root in the place where you’re born,” she said.

“Westerners who come to Ubud sometimes seem lost in that sense. They’re not taking responsibility to establish themselves completely in this place, because they feel like it’s too controlling whereas it’s more about taking a decision to go where you want to go.”

She instills discipline she learned in Europe to the Balinese women she work with, who are used to more relaxed work ethos. On her retreats, she asks the Balinese women questions about their mission in life and encourages them to develop more skills to match the foreigners’.

“They get married, have children and make sure that their family stays happy. They don’t think about their own happiness. Balinese women are afraid to be different. They’re doing so much for the island but they’re unseen,” she said.

It’s for that reason Luh wants to help them and change their mindset.

When other women ask her about why she’s not married yet at age 38 she now responds: “Do I look miserable to you? I look happy right? Then please ask a different question instead of assuming something is wrong with me.”

This article was first published in Inclusive Journalism website.