As a child, Sujala Pant, Deputy Resident Representative United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Indonesia, often heard people ask her father why they never tried for a boy after having her and her sister. His father would ignore this kind of comments.

“When I was going to university overseas, people would be like, ‘Why are you spending so much money to send your daughter out to study?’ And he was so adamant that the most important investment he would ever make would be in our education,” Sujala said during an interview with Madgalene at UNDP office in Jakarta.

Such discriminative view was unusual for Sujala, who was never exposed to it within her own family. Looking back, however, she realized that having a family that treat girls and boys equally was a privilege likely shaped by her father’s unconventional outlook on gender role.

“As the main breadwinner of the family, it really was his decision to go this way or that way. And he chose … to stand up to society and their kind of misconceptions,” she said.

Also read: Sharing Domestic Roles: More Said than Done

“As much as I’ve had many women role models in my life, I’m also extremely aware of the role that my father or grandfather have played. And I think that translates into the workplace as well. So, in offices, where you have senior managers or leadership who are men, I think their commitment to gender equality and empowerment (is important), but also putting that into action through very concrete little steps that they can take is crucial.”

Sujala’s personal experience shows the importance of mainstreaming gender perspective, whether to make policies to prevent discrimination, to create initiatives that empower all, or to build a more inclusive culture. Underlining this effort is the awareness and acknowledgement that women and men have different needs, different priorities, and different challenges.

She gave an example of a recent study on why women always feel colder in office environments than do their male counterparts. The research found that most office buildings set their air conditioner temperature based on the metabolic rate of men. This had its root in the ‘60s and ‘70s, she said, when the majority of people in the workplace were men. Yet this baseline has continued to be used to this day, causing millions of women to wear sweaters and jackets at their desks.

“Once the unpacking of why was understood, then adjustments can be made, right? It’s the fact that physiologically we’re different, that we have different needs, and this needs to be understood so we can move forward on the responses – that’s what mainstreaming has to be about,” she said.

Another example that she cited was the fact that during disasters like flash floods, girls and women were more likely to drown than boys and men. Social and cultural reasons play a factor in this: in many areas girls and women are not encouraged to take up swimming, or the access to public spaces like rivers or swimming pools may be more restrictive to them. When disasters strike, they don’t have the reflex and knowledge to swim to potentially survive, she said. These facts, need to be considered in developing disaster risk reduction programs.

“So, it’s not just addressing disaster risk response from a technical perspective. You also have to build in perhaps swimming lessons for girls of affected communities, for your responses to have the chance to be successful and sustainable,” she said.

At UNDP, gender empowerment and women’s equality is a guiding principle for everything it does. Underscoring this is women’s participation in the process of making public policies or initiatives. But she warned that this must not be done in a tokenistic way. Empowerment is beyond numbers – women’s participation must be meaningful.

“I think maybe 20, 30 years ago, we used to say: number of women participants. And if you had a high level of women participants, it was like, great job. That’s enough,” she said. “But it’s not. We know it’s not enough, because you could have women in the room, but if they’re not able to say anything, if they’re not claiming the space or given the space, then it doesn’t matter.”

Gender intervention also needs to be contextualized, factoring in the specific community, culture, and individuals, instead of done with a “cookie-cutter approach”. Listening intently is the key.

Also read: Gen Z Boys’ Attitudes To Feminism Are More Nuanced Than Negative

Gender Mainstreaming in Indonesia

In Indonesia UNDP’s work is aligned with the government’s priorities on gender equality and women’s empowerment, particularly the mid-term and long-term development plans. The focus is on shifting economic power relations between men and women, equipping women to have the necessary skills and capacities to contribute meaningfully, and in ensuring or enabling ways in which women can be part of decision making.

UNDP’s portfolio on climate-change related work, for example, includes training women to be forest rangers to combat wildlife trade project, and area that is not traditionally associated with women.

“In many areas, the forest is valued beyond its economic value. It has societal and intrinsic cultural values as well. And what we know is – and this is not to say men don’t – but we also know that when women feel like they’re part of that effort to protect the forest and protect it from unsustainable use – if they’re more involved – it’s more likely to be successful.”

Its work also revolves around the transition towards more renewable and sustainable sources of energy, which is expected to create some economic disruptions. Traditionally women have not been visible in the energy sector, making up about 5 percent of decision makers in energy companies, she said.

“But the energy transition creates opportunities. So, it will mean, there will be more investments in the whole value chain that will enable renewable energy sources. So that will require new skills,” she added.

There also needs some social protection to cushion people as changes disrupt their lives, and UNDP aims to empower women to contribute to this effort with the right kind of skills and capacities.

UNDP also works with micro, small and medium enterprises, a huge contributor to Indonesia’s economy and a largely informal sector mostly run by women, targeting women-led businesses to help them develop business skill and have access to funds, she said.

Programs aside, gender mainstreaming in UNDP also applies closely to its operation. When procuring services, for example, UNDP selects its bidder based on criteria such as having gender-sensitive policies as part of their business operations, being led by women, or having a large number of women workforce.

Within UNDP, achieving gender parity in human resources is also crucial, and this goes beyond mere numbers. Currently, UNDP Indonesia has 45 to 55 percent men-women ratio at different levels. But women overwhelmingly fill the administrative support functions, while there are slightly more men in the professional levels and positions.

“We want to change that, so when we recruit for professional positions, there will be considerations for strong women applicants. Likewise, in the general services category, we will pay attention to ensure that men are also not underrepresented,” she said, adding, “And that’s how you address some of these systemic changes that we see.”

For its work in gender mainstreaming, UNDP Indonesia has been awarded the gold seal for gender equality, the first UNDP office in Asia Pacific to have received the acknowledgement.

Also read: My Patriarchal Extended Family and Why I Dread Spending Holidays with Them

Gender Mainstreaming Impact and Future

In early 2000 following Reformasi, several initiatives were designed to encourage more political parties to have more women representation, one of them is the legal requirement for parties to have 30 percent of women as their legislative candidates. Though the number women legislators are still below that number, in 24 years women parliamentarians have risen by four times to 20 percent today.

UNDP is also working closely with the Ministry of Finance on looking at ways to “climate align” Indonesia’s public budget.

“There have been efforts to look at how much from the budget can be tagged or identified as climate relevant, what of that is also specifically addressing gender dimensions,” Sujala said. “Because we can have all the best commitments in the world, but if there’s no financial resources, you can only go so far, right?”

Asked if top-down gender mainstreaming can shift gender norms and behaviors towards a more inclusive and equal society, Sujala expressed her optimism. Having policies is just the beginning, she said, implementing them requires continued reflections and efforts from everyone, the government, academia and private sectors. But what will eventually change society is when it’s practiced at individual level, when people lead by example.

“It can be small actions, but it has to be led by each and every person to make little changes within the circle of control that they have, within the influence that they have. And if many of us do that, then surely there will be the kind of irreversible change that we would hope to see,” she added.

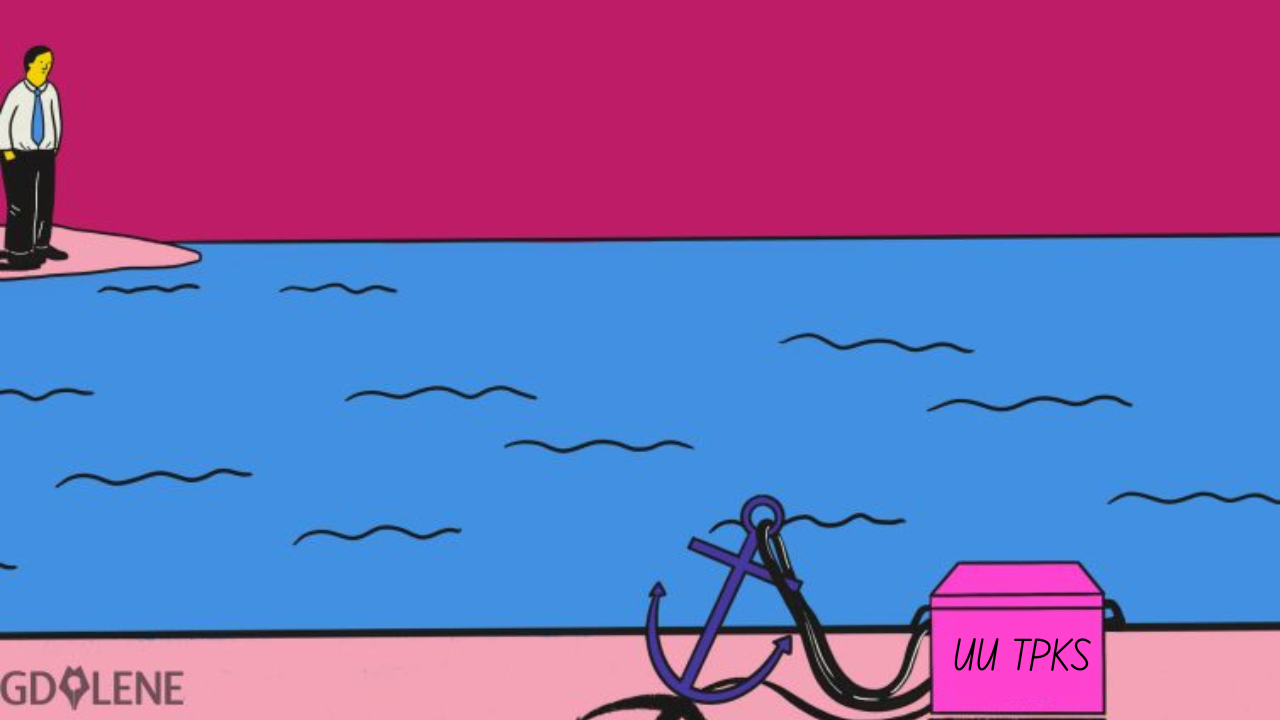

Ilustrasi oleh: Karina Tungari