The Truth about Manila: The City Has a Lot to Offer Than People’s Prejudices

When I told my friends I was going to Manila for a solo trip, they shared the same reaction: “Is there anything interesting there?”

Well, that kind of reaction was understandable. I could barely name a Filipino popstar, except Christian Bautista with his one hit song, “The Way You Look at Me”. All I have in mind about this country is its fascist former leader, Rodrigo Duterte.

I was also convinced by my old friend who happened to visit Manila years ago, she said that there is nothing to explore there, saying the vibe was not so different from Jakarta.

I might not have one reasonable purpose to fly all the way to the Philippines, but I could not resist the call from Niall Horan—member of One Direction, whose concert was held at Mall of Asia Arena, Manila. Since the ticket concert was way cheaper than any superstar concert in Jakarta, I could not help but go to the ticket war and saved myself one seat.

So, I thought why not experiencing Manila first hand and explore their culinary heritage? Who knows, I might cross path with a single and Catholic Piolo Pascual-lookalike? (Please pray for me for the latter)

Also read: Solo Female Traveler in ‘Non-Women Friendly’ Destinations

Disproved the Prejudice of Local Food

I landed in this “Pearl of Orient” country, having zero idea about Filipino cuisine except for adobo—made with marinade and simmered meat, seafood, or vegetables in vinegar, soy sauce, and garlic. It actually looks like Indonesian meat stew semur, but I had no idea what it would taste like because there is barely a Filipino restaurant in Jakarta.

Many say this is because because Filipino cuisine is not desirable for Indonesian tongue. The cuisine tends to be more oily, lacking spices, too much vinegar, also tangy and sour from calamansi as the key ingredient. Meanwhile, Indonesians love umami — spicy dishes with generous sprinkles of micin.

Those facts led me to the question: how come we have different tastes in food and culture, when geographically speaking, the Philippines is not really that far from Indonesia? If you look at the maps, it is exactly above Borneo.

I did my research, and found, unsurprisingly, that colonization is a culprit. When the Spaniards came and colonized the Philippines, they saw the local cuisine as primitive and inferior, then forced the Filipinos to serve Spanish dishes.

It significantly changed the Filipinos culinary identity. Food became a home-cooking culture rather than part of the community that bonded people. There was a time where the Filipinos were feasting on their own food, as a form of rebellion to colonization and how they had enough being seen and treated as second class citizens.

When a friend invited me to have early dinner at Manam—a restaurant that serves classic Filipino dishes, I had no expectations on what the food would taste like. One thing I was aware of is that Manam is top notch, since I have seen the locals recommending it on TikTok.

That night was the first time I devoured Filipino cuisine: sisig, pancit palabok, chicken inasal, also pork and chicken chicharron. Among those dishes, pancit palabok was my favorite. It is crispy noodles topped with the spectacular yellow sauce and various toppings: squids, prawns, and hard-boiled eggs. Once the sauce was poured, the noodles absorbed it and changed the texture—quite similar to mie titi from Makassar, South Sulawesi.

None of the food I ate at Manam were close to people’s prejudice about Filipino dishes. Yes, some of it has a sour taste from the vinegar, but that was not dominating the flavor. Instead, the combination of sweet, tangy, savory, and sour was expanding my palate.

I do realize eating at Manam was a luxury experience since they have twisted the dishes to another level. I believe that is what makes it different from any other restaurants or street vendors. However, that does not mean I did not try local food from various places.

On Tuesday afternoon, I had halabos na hipon—garlic butter shrimp—for lunch at Gubat in Quezon City. They serve Filipino comfort food in kamayan style, or eating with your hands. When the garlicky shrimp entered my mouth, it reminded me of the food back home. That moment I discovered, Indonesia and the Philippines have similar tastes in food.

Also read: I Left Indonesia to Pursue a Life Without Fear

Surviving in “Mexicans of Asia”

Though people say things about Filipino food, I have no doubt I would like it. What concerned me was personal safety with Duterte’s drug war stuck in my head. Though he’s no longer in office, his much criticized policy lives on under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. I even thought of the possibility of someone slipping a drug in my bag. But since I was more intrigued to see what Manila has to offer, I decided to bring a safety kit: personal alarm keychain, portable door lock, whistle, and padlock for my backpack.

It might not capture the reality, but all my prejudices against Manila turned out to be largely unfounded. I landed in the morning because I planned to stroll around a city in Metro Manila, Makati. Unlike in Jakarta, I walked a lot there because Metro Manila has wider sidewalks and, surprisingly, got zero catcalls. If it was not because of the heatwave, I would have walked everywhere, but the scorching sun on my face was too much after a while.

Fortunately, public transportation is well integrated there. I was astonished to see how some big malls are connected by bridges and the MRT Station. It makes it more accessible for people who want to jump into another mall. There is also a bus terminal in the basement of the shopping mall. Their interconnectedness is something that we can learn from. Yes, Jakarta, I’m talking about building bridges across Grand Indonesia and Plaza Indonesia. Even MRT Bundaran HI station should be accessible inside the malls.

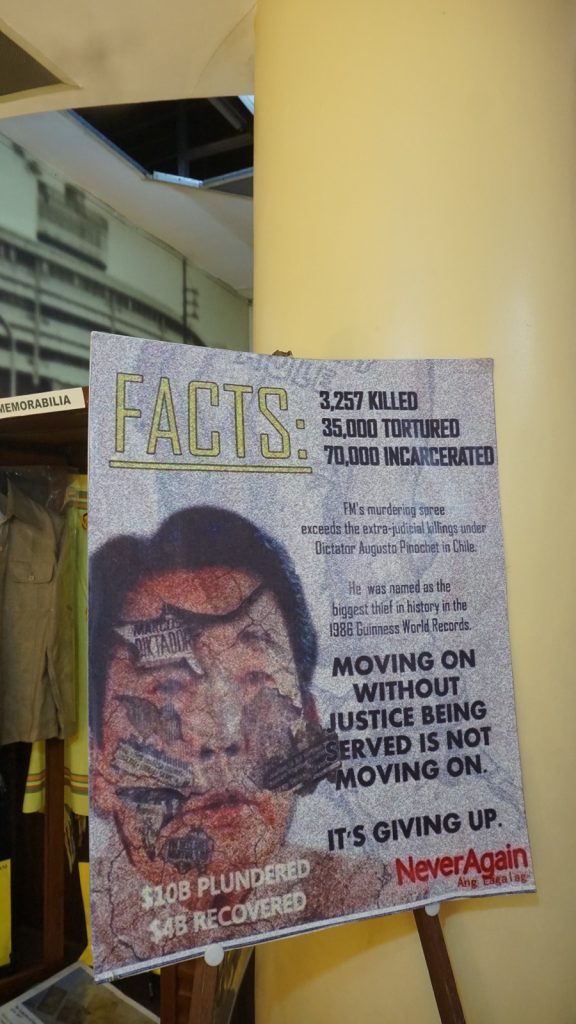

To know better about the Philippines, I explored its history in Museo ng Bantayog in Quezon City. Owned by Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation, the museum displays memorabilia and pictures of Filipinos’ battle for freedom. The museum covers the era starting from the Spanish and American colonizers until the time of former President Ferdinand Marcos’ Martial Law. The last part show media publications and repression paintings that criticize Marcos’ administration.

One of the displays that stole my attention was an infographic of Marcos’ dictatorship. The data shows about 3.000 people were killed, 35.000 tortured, and 70.000 incarcerated under his dictatorship. Guinness World Records in 1986 named Marcos as the biggest thief in history.

I asked my friend if this dark history is officially being recognized by the government.

“The government created their own version of Marcos’ reign. But it depends on the school, some of them took the students here to learn the truth,” he explained.

I admired how they preserved the historical memory, and could not help but wonder if someday Indonesia will have a museum exposing the New Order regime. During the dark years of Soeharto’s dictatorship, the media were censored by the government and everything related to left ideology was restricted. Books and media organizations critical of the government were banned: Tempo, Editor, Detik. Many resources proved that Soeharto was also the mastermind behind the pro-democracy activists kidnapping and enforced disappearance. But our country has never officially reflected on these facts nor the government ever recognized the regime’s “sins”. A museum can be an alternative medium to learn our history.

Also read: Travelling with Strangers

Catholicism in The Philippines

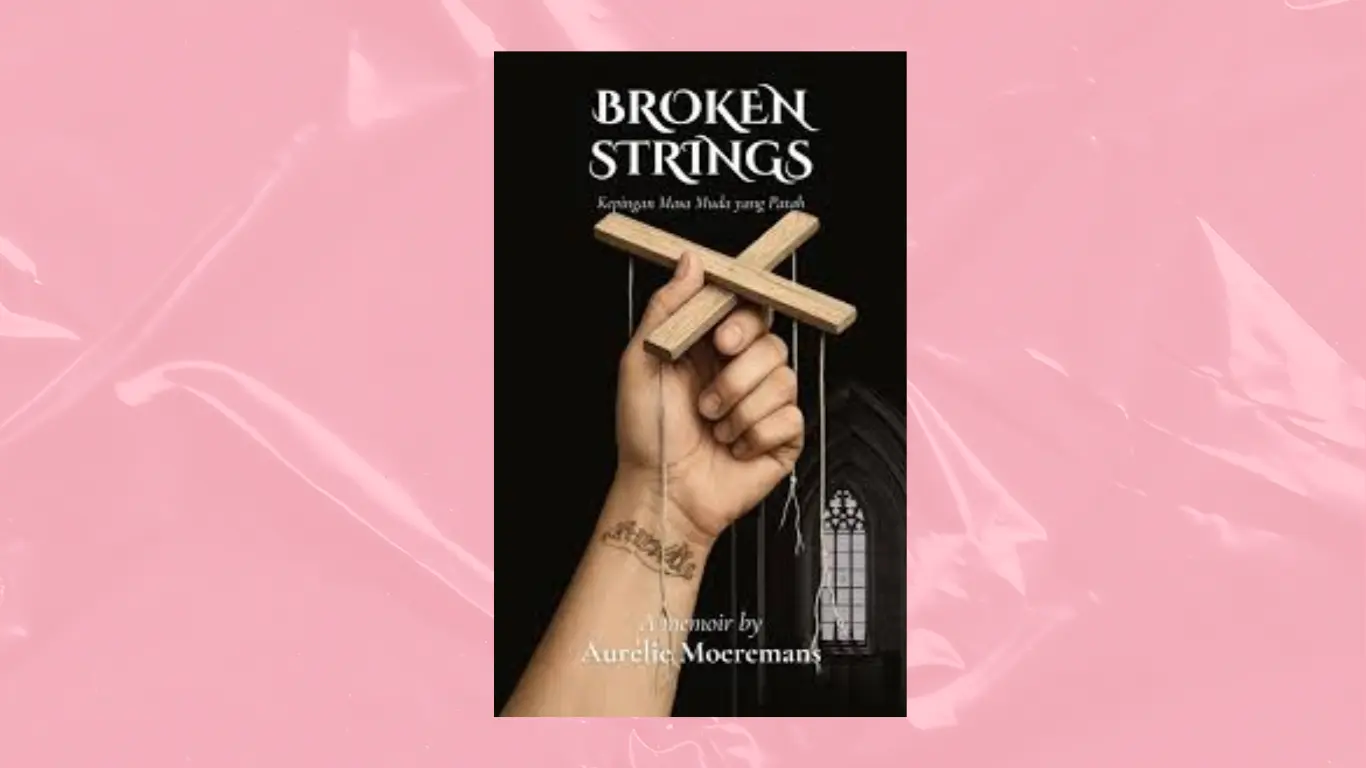

As a minority in Indonesia, I have never seen any museums showing Catholicism. Though I’m not religious, seeing how faithful Filipinos as Catholics are shown through arts and movement touched me.

When I looked behind the infographic, a statue of Our Lady of Fatima on the display of the People Power Revolution of 1986 caught my eyes. At the time, millions of Filipinos marched along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) to end the dictatorship of Marcos, and begin the new era of freedom and democracy. During the revolution, protesters brought Our Lady of Fatima statue and rosaries to protect themselves from Marcos’ own men who might inflict violence upon the protesters.

(Photo: Aurelia Gracia)

The devotion to Mother Mary symbolizes that Catholicism in the Philippines is not only a personal affairs. Religion is present in most households, institution, and culture.

People sell anting-anting—a charm to prevent any physical weakness or exorcism of evil spirits—at the market. Then to honor Santo Niño, Filipinos held the Sinulog Festival every third Sunday of January in Cebu. There are several forms of celebrations to show the devotion to Santo Niño: multiple masses, dance parade, and reenactment of Catholicism arrival in Cebu.

Unfortunately, Catholic values also influence how the laws are formed. It is illegal to undergo abortion in the Philippines because of the demand of the Catholic hierarchy. According to the first Philippine Constitution, the government is obligated to “protect the life of the unborn from conception.” Therefore, people who get abortion can be in jail for up to six years.

The irony of the situation is palpable since criminalization actually prompts some women to seek unsafe procedures which risks their lives. According to a CNA documentary in 2019, 600 thousand women buy illegal drugs every year to abort their pregnancy. Unprescribed by doctors and illegally distributed make these abortion drugs fatally harmful to the women.

One popular option is pampa regla, a concoction that can end pregnancy. I spotted three or four stalls at Quiapo Market—only a few meters away from Quiapo Church—selling the medication. I tried to ask some questions out of curiosity, but they were not really open about the products, because it is illegal to sell them.

As might be expected, women in the Philippines are the ones who also have to bear the consequences: A thousand of them die each year as a consequence of unsafe abortions, according to a 2013 report by Guttmacher Institute.

Perhaps the situation in the Philippines is not that different from what women experience in Indonesia and other countries where our lives and bodies are controlled by society and the government.

The dark side, aside though, I have no regrets coming to Manila. Contrary to what the preconceptions on it, the city has a lot to offer: culinary heritage, culture, historical sites and events. And though I never did find a single Catholic Piolo Pascual-lookalike, I discovered a lot more than I expected. And the more you discover, the more you experience.