72 Hours of Social Media Silence: How Officials’ Online Inaction Undermined Disaster Management in Sumatra

“I lost contact with my family for three days. I couldn’t contact them. I just couldn’t,” Khalida Zia’s voice cracked as she recounted the day floods engulfed much of Sumatra.

Speaking to Magdalene over the phone from Aceh on December 2, just days after the disaster, she sobbed as the memory caught up with her.

“There was no signal at all. No electricity. It was dark. And water was everywhere. Mud, water, and mud.”

In the early hours of November 26, floodwaters began swallowing villages across Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. By dawn, Khalida’s family home in Bireuen was already inundated with mud and water. Electricity towers collapsed. Entire districts went silent. From the provincial capital of Banda Aceh, Khalida could only watch the disaster unfold through fragmented news reports, unsure whether her parents were alive.

“The first day I realized I couldn’t reach them, I immediately became extremely distressed,” she said. “My only information came from the media.”

With barely any knowledge about the situation nor directions from authorities, Khalida did the only thing she could think of.

“I initiated a movement to collect aid through donations through my personal account. It turned out that that was the only aid that had arrived then.”

Later, she realized that she had initiated what were some of the first aid efforts in the region. When volunteers finally reached evacuation sites, what they found was devastating.

“At the camps, people said no one had come to help them,” Khalida recalled. “The local government had not come at all.”

“I’ve become like a governor. I’m constantly being contacted now. Because I was the only one who went to the evacuation sites quickly and organized things, even leading the response without any documentation.”

With little to no warning of the disaster and all connection cut off physically and online, this raises the all-important question: what were official government channels communicating and doing during the crucial first 72 hours of the Sumatra flood disasters?

Also read: Kala Bantuan Tak Datang: Relawan Topang Sumatera di 72 Jam Pertama

Why This Story Needed to Be Told

On November 28, the head of the National Agency of Disaster Management (BNPB) said the disaster was not as “harrowing” as portrayed on social media. Subsequently, President Prabowo Subianto announced on December 1 that a ‘national disaster status’ was ‘unnecessary’ as the situation was ‘improving’. Foreign Minister Sugiono further rejected foreign aid on December 5, stressing the Indonesian government’s disaster management capabilities.

By 19 December, atalities had escalated to 1,071, with the number of displaced rising to 111,620 people, including 58,333 women (52 percent).

This is especially concerning in light of Article 26 of Indonesia’s 2007 Disaster Management Law, which mandates the prioritisation of vulnerable groups defined in Clause 2 of Article 55 as the elderly, people with disabilities, children, and pregnant and breastfeeding mothers.

Currently, women are up to 14 times more likely than men to die in disasters. This is largely attributed to women’s disproportionate responsibility for caring for other vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. This limits their mobility in evacuation and increases their physical and psychological strain in the aftermath of a disaster.

These risks are compounded by unequal access to aid, inadequate hygiene products and sanitation, and heightened exposure to sexual harassment and domestic violence, particularly when relocation sites lack gender-segregated accommodation, according to Andy Yentriyani, Chair of Komnas Perempuan.

Taken together, these conditions prompted us to examine the government’s rescue efforts through social media and see how it is performed and framed.

Why Social Media?

Our investigation focused solely on officials’ social media communication instead of other channels such as press releases or mass media reporting.

In Indonesia, social media, particularly Instagram, has become a primary channel of communication for officials. Presidents, ministers, governors, and local leaders routinely use social media to release statements, document field visits, and showcase government responses during moments of crisis.

As such, social media offers valuable insight into how officials and institutions understand and frame crises, while also revealing how disaster response and coordination are publicly performed in real time.

Further, social media plays a central role in informing communities affected by the Sumatra floods. As floods disrupted electricity and telecommunications across Sumatra, many residents turned to these platforms to seek updates, safety information, and government action.

Our Methodology

To assess how effective disaster response and support were for affected communities, we applied methods developed in Universitas Indonesia’s Crisis Communication in Non-Tectonic Tsunami Disaster Management research. Specifically, we looked at whether officials’ portrayals of “help” matched what victims actually received and experienced, and how government actions were presented on their Instagram. We are particularly attentive to the government’s effort to protect vulnerable groups – especially women – and to meet their specific needs.

Our analysis focuses on the first 72 hours following the disaster, which UNESCO identifies as the most critical timeframe for emergency response and relief efforts.

Reality Check: Interview Testimonies

The first step of our investigation was to interview witnesses to explore the lived realities in Sumatra.

We sought to interview victims directly, but unstable internet access and prolonged blackouts in disaster zones limited us to speaking with volunteers. Many were moving between severely affected areas and those less impacted to distribute aid.

We interviewed five volunteers in Aceh, North Sumatra and West Sumatra. It is important to note that Aceh was also one of the hardest-hit regions in the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami that killed nearly a quarter of a million people.

And here’s what the volunteers have to say:

Also read: Kisah Perempuan yang Selamat dari Bencana: Jalan Kaki Puluhan KM, Kelaparan, Melihat Banyak Jenazah

How We Analysed the First 72 Hours

The testimonies reveal how the government’s help has been inadequate across North Sumatra, West Sumatra and Aceh.

To understand the government’s perspective, we examined the Instagram accounts of 15 government officials. We have specifically targeted Instagram as it has been the main medium of communication for politicians in Indonesia.

The accounts analysed here belong to officials and agencies that are legally and structurally responsible for disaster response in Indonesia, from national to provincial authorities.

Accounts examined include national-level politicians and institutions with decision-making authority over disaster relief efforts. Among them are seven governors and mayors representing the regions most severely affected, based on fatality data published by BNPB.

These roles are mandated to appear and act in the first hours of a disaster. Our analysis strives not to assess individual personalities, but to examine how Indonesia’s disaster response operates through its formal institutions.

Guided by UNESCO’s 72 hour rule and Indonesia’s disaster management law, we decided to track national institutions and politicians’ posts from 25 to 27 November (the first 72 hours) using a content-monitoring sheet. Each entry was coded by content type such as graphics, reels, or marked as N/A if no post or irrelevant posts are made.

We also recorded whether or not the disaster-related contents had any mentions of vulnerable groups’ needs.

Through analysing their content, we can understand what the government chose to highlight as a priority, the public narrative it seeks to construct and what it chose not to show at all.

Social Media Monitoring Findings: What Has the Government Done Within the 72 Hour Timeframe?

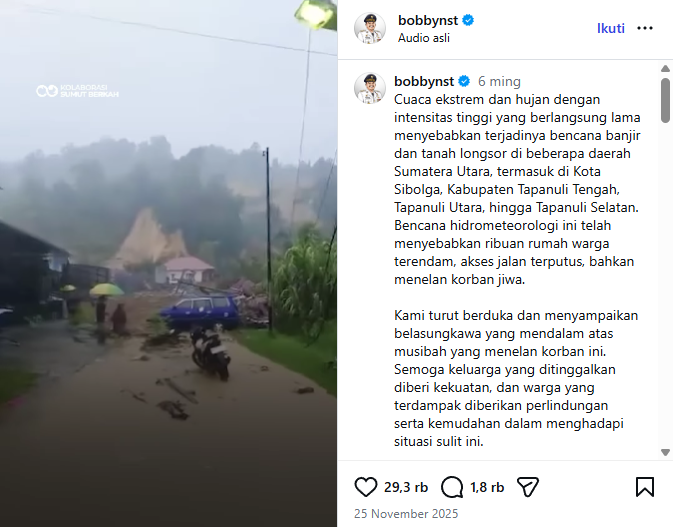

Finding I: Of the 15 government officials’ accounts we examined, almost half did not post about the flood within the first 72 hours. Three others posted late within that same period.

Among those who failed to post were President Prabowo Subianto; Aceh Governor Muzakir Manaf; the Ministry of Social Affairs; the Ministry of Health; North Aceh Regent H. Ismail A. Jalil (Ayah Wa); Sibolga Mayor Akhmad Syukri Nazry Penarik; and East Aceh Regent Iskandar Usman Al-Farlaky.

Notably, the President, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Social Affairs are among the accounts with the largest followings, followed by the Governor of Aceh.

Indeed, the most recent reel Prabowo published nearest to the dates was a celebratory reel wishing followers “Happy Galungan and Kuningan” for the Hindus in the country. All posts from Muzakir Manaf in the period of November 25th – 27th were about officials’ visits such as a formal meeting with the Coordinating Minister for Political, Legal, and Security Affairs Djamari Chaniago, and a courtesy visit with Nurul Akmal, an Acehnese weightlifting athlete. The Ministry of Social Affairs only published its first disaster-related content on 30 November, about its distribution of logistics and communal kitchens for flood victims in Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra. The Ministry of Health only had one post titled ‘Pray for Sumatra’ on Nov 28.

Their silence on the disaster during this critical period represents a missed opportunity to disseminate urgent information, provide guidance to affected communities, and demonstrate institutional leadership during the most time-sensitive phase of disaster response.

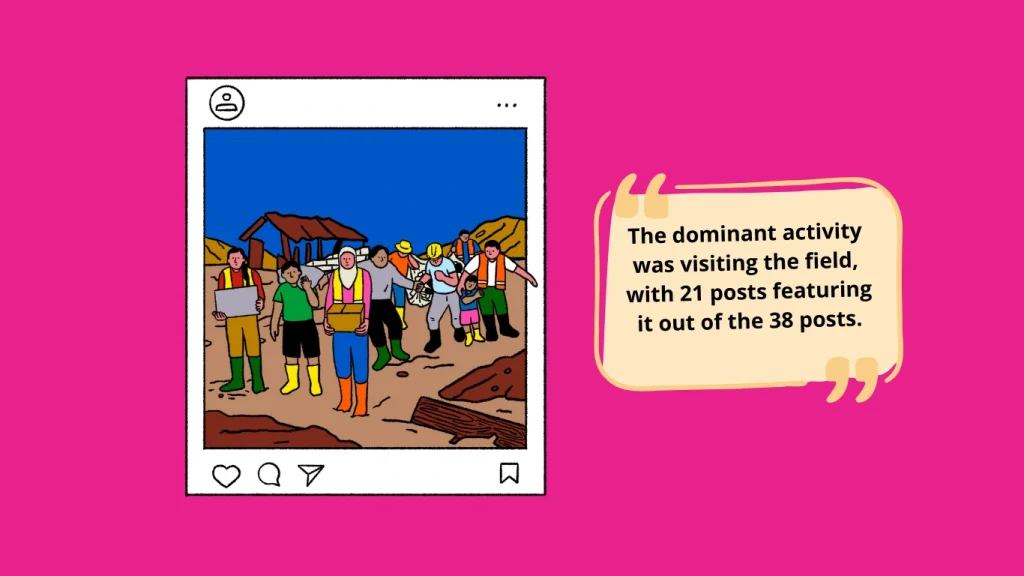

After identifying those who posted, we examined the activities featured in their content. Excluding infographics, those that showcased activities involved mostly operational fieldwork. Some content also portrayed multiple activities.

Activities: What were they seen doing?

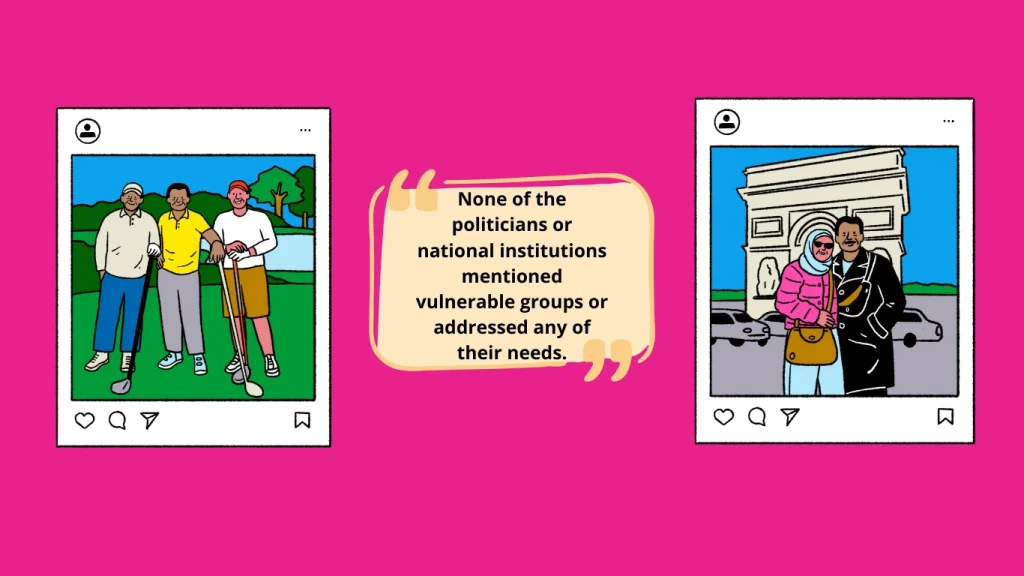

Finding 2: Most on-the-ground content focused on showcasing presence, with limited emphasis on direct engagement or the needs of vulnerable groups.

While posts from agencies like the disaster management agency Basarnas featured hands-on engagement such as evacuation and rescue efforts, many officials, often accompanied by other officials, delete were seen listening passively or speaking to cameras in the disaster sites or amid crowds. Most interactions with civilians were in the form of quick montages instead of longer forms, emphasizing quantity over quality of conversations.

Notably, posts that focused on greeting or comforting civilians disproportionately featured women and children. There was also minimal content documenting conditions inside refugee camps or visits to evacuation sites during the first three days.

None of the posts addressed vulnerable groups’ needs nor offered practical information such as how to access assistance, identify evacuation routes, or locate temporary shelters.

Visual Framing and captions: Affective tone of the posts?

With the activities identified, we then examined how these activities and information were framed.

We examined the visuals used, visual framing, and caption tone.

They are then sorted into coding types.

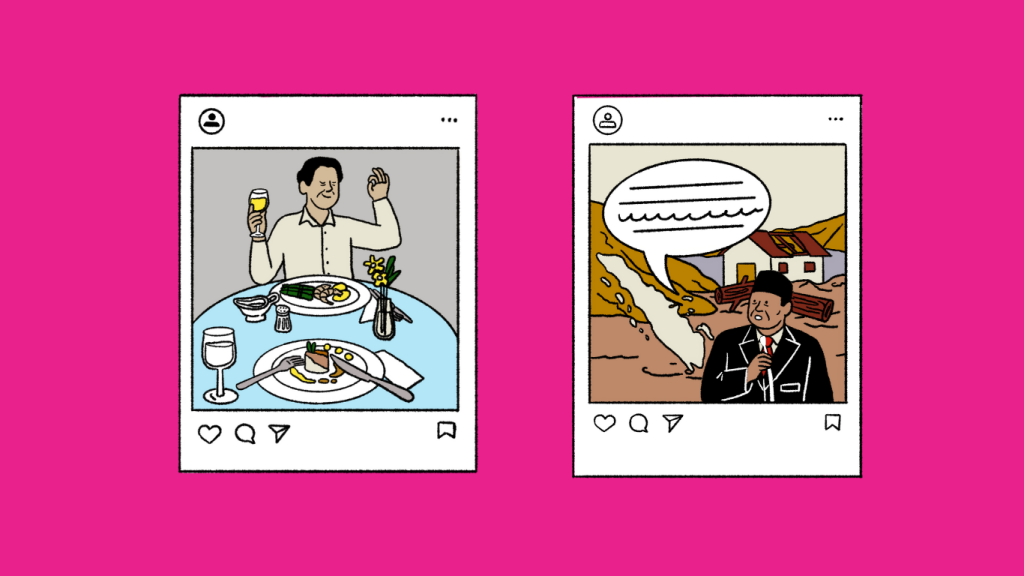

Our aim was to assess whether government responses amounted to performative gestures rather than substantive action.

Northwestern University researcher Iza Ding defines “performative government” (or “performative governance”) as the state’s theatrical use of visual, verbal, and gestural symbols to project an image of good governance, distinct from the actual achievements of substantive policy goals.

Identifying visual framing enables us to examine how officials’ content shapes viewers’ perceptions.

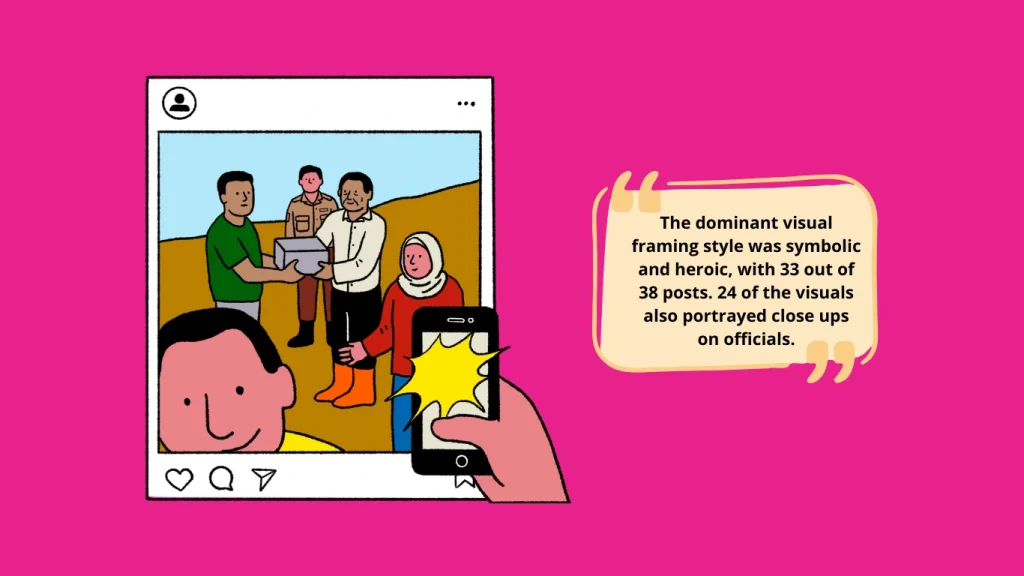

Finding 3: Across all posts, there was a strong tendency toward heroic and symbolic portrayals.

Nearly half of officials’ posts employed heroic or symbolic visual framing rather than needs-oriented communication.

Heroic framing was commonly produced through close-up shots of officials walking or traveling through heavy rain, mud, or damaged terrain. Some officials were well-dressed and shielded by their team with an umbrella, while those around them were visibly drenched. This further reinforces an us-versus-them dynamic that positioned officials as elevated figures rather than co-participants in disaster response.

Most piece-to-camera speeches did not include concrete promises, next steps, or policy recommendations.

Unlike Basarnas that were seen engaging in evacuation and recovery, most officials were merely speaking or surveying. Some were sending prayers or condolences.

Many of the officials’ speeches often revolved around descriptions of the situation or mere recital of statistics such as the number of casualties or infrastructure destroyed. Some even attributed their failure to access certain areas to external factors, with some talking about their own achievements or how hard disaster management and recovery efforts have been.

There were those who engaged in rather dramatic movements and heroic portrayals of themselves.

Their emphasis of their physical presence at hard-to-reach disaster sites and their emphasis on the severity of the disaster creates a persona-centered framing of endurance and sacrifice. This undermines rescue plans and outcomes, rendering their actions symbolic. Content showing snippets and montages of meetings (bureaucratic), often in elaborate, grand meeting rooms, also portrays formality and bureaucracy rather than practicality.

In terms featuring of civilians, we noted a high tendency for officials to choose vulnerable groups like women and children. These interactions were mostly in the form of quick montages, without sustained engagement or dialogue. This does not only amplify heroic framing by positioning the all-male officials as benevolent, paternal figures, it also disguises reassurance as assistance – without addressing the true needs of the vulnerable.

Captions analysis

Finally, we examined the captions accompanying posts on these official accounts.

Captions play a crucial role in contextualising visual content, reinforcing key messages, and increasing visibility through platform search and algorithmic reach.

Our analysis found that captions consistently reproduced the same performative patterns observed in the visuals.

Captions tended to be official-centered, emphasizing achievements like completion of site visits and meetings, rather than victim-centered accounts detailing needs met, people reached, or remaining gaps.

Several captions engaged in explicit self-praise or institutional praise, reinforcing authority and competence without offering practical information.

Others repeatedly attributed the disaster to “extreme weather,” shifting attention away from structural or policy factors such as failures in land-use regulation and environmental management. In fact, it is worth noting that North Sumatera Governor Bobby Nasution, despite acknowledging the disaster on-time, has actively promoted palm oil cooperatives and logistics expansion as a development success. Similarly, Agam Regent Benni Warlis publicly celebrated large-scale oil palm replanting programs as symbols of productive governance.

Taken together, captions were used less as tools to disseminate urgent updates, guidance, or resources, and more as extensions of visual performance.

Also read: Banjir di Sumatera Utara: Ketika ‘Apa Kabar?’ Datang Terlambat

Soap Opera-like Empathy

As shown through our analysis, there was a clear lack of official acknowledgement of the disaster during its most critical early phase.

Even when officials did communicate, they relied heavily on heroic and symbolic portrayals, evident in frequent close-up shots centring officials and captions emphasising self-praise and image-building.

Officials’ failure to address the needs of vulnerable groups in their social media posts also reflects a broader failure to identify, prioritise, and respond to their primary needs.

Many officials have also referred to the flood as the result of “extreme weather”, downplaying the deeper, underlying causes of the large-scale flooding.

Sari Moniq Agustin, a communications lecturer at the University of Indonesia, likens the government’s visual narrative to a “soap opera script” of staged empathy and hard work.

“When an official’s face dominates the frame, it signals an artificial empathy because it relies solely on symbols,” She told Magdalene.

Echoing our findings, she observed the same tendency in officials’ posts to showcase actions such as “leading” coordination efforts and “saving” citizens, which she described as performative.

“This reflects how the current government views its people: [its] symbol of [power] matters more than realities on the ground. For me, this is a clear form of visual exploitation,” Moniq said.

When asked why officials appear fixated on symbolic portrayals rather than the delivery of concrete, needs-based action, Moniq pointed to two factors: poor cross-departmental coordination in disaster management planning and a deeply rooted “waiting for orders” culture.

This is most evident when the President and key disaster-response agencies (e.g Basarnas, the Ministry of Social Affairs, and the Ministry of Health) remain silent on social media during the critical early hours of a crisis.

Under such a culture, governors and agency heads often hold back action and public communication until higher authorities (e.g president) have articulated their views on the disaster and signalled a general direction.

This caution is often driven by a fear of making mistakes and causing reputational harm to superiors.

“When a state institution remains silent, it means they are waiting for coordination. It shows that their only concern is the government’s image,” she said.

Looking Ahead: Reclaiming Disaster Communication for the Public Good

Even after the initial three days, official communication remained fixated on personal and political image. The faces of president, governors, and mayors continued to dominate social media posts.

Arguably, the Indonesian government’s obsession with self-presentation can carry real and potentially life-threatening consequences by limiting victims’ access to timely updates and practical guidance.

For vulnerable groups such as women and children, the consequences are even more severe. Not only are women and children reduced to exploitable visual tools that reinforce officials’ fatherly, heroic image, but the constructed compassion that accompanies this also blurs the line between real action and performance. This then shields authorities from scrutiny and deflects their responsibility to deliver concrete support.

Ultimately, for disaster communication to fulfil its public function, it must be grounded in real action and oriented toward victims’ needs.

As Moniq noted, effective public communication during disasters should prioritise emergency updates, safety instructions, logistics, and aid information.

With a shift toward needs-led, victim-centred engagement, social media can become a tool for transparency and coordination — one that has the potential to save lives during moments of crisis.

This article has been re-edited by authors on January 8, 2026 at 13:04 PM WIB.

This article is part of Magdalene’s data journalism series. Read the other stories here.

Project Lead / Editor-in-Chief:

Devi Asmarani

Special Reports Coordinator:

Jasmine Floretta

Editors:

Purnama Ayu Rizky, Devi Asmarani

Reporters:

Andrei Wilmar, Jasmine Floretta, Purnama Ayu Rizky, Sharon Wongosari, Ting-Jen Kuo

Data Analysts and Visualisation:

Sharon Wongosari, Ting-Jen Kuo

Graphic Assets & Translation:

Chika Ramadhea

Illustration / Graphic Design:

Karina Tungari, Bima Nugroho

Social Media: