In Bali, Fishers Shift to Solar-Powered Boats, but Challenges Remain

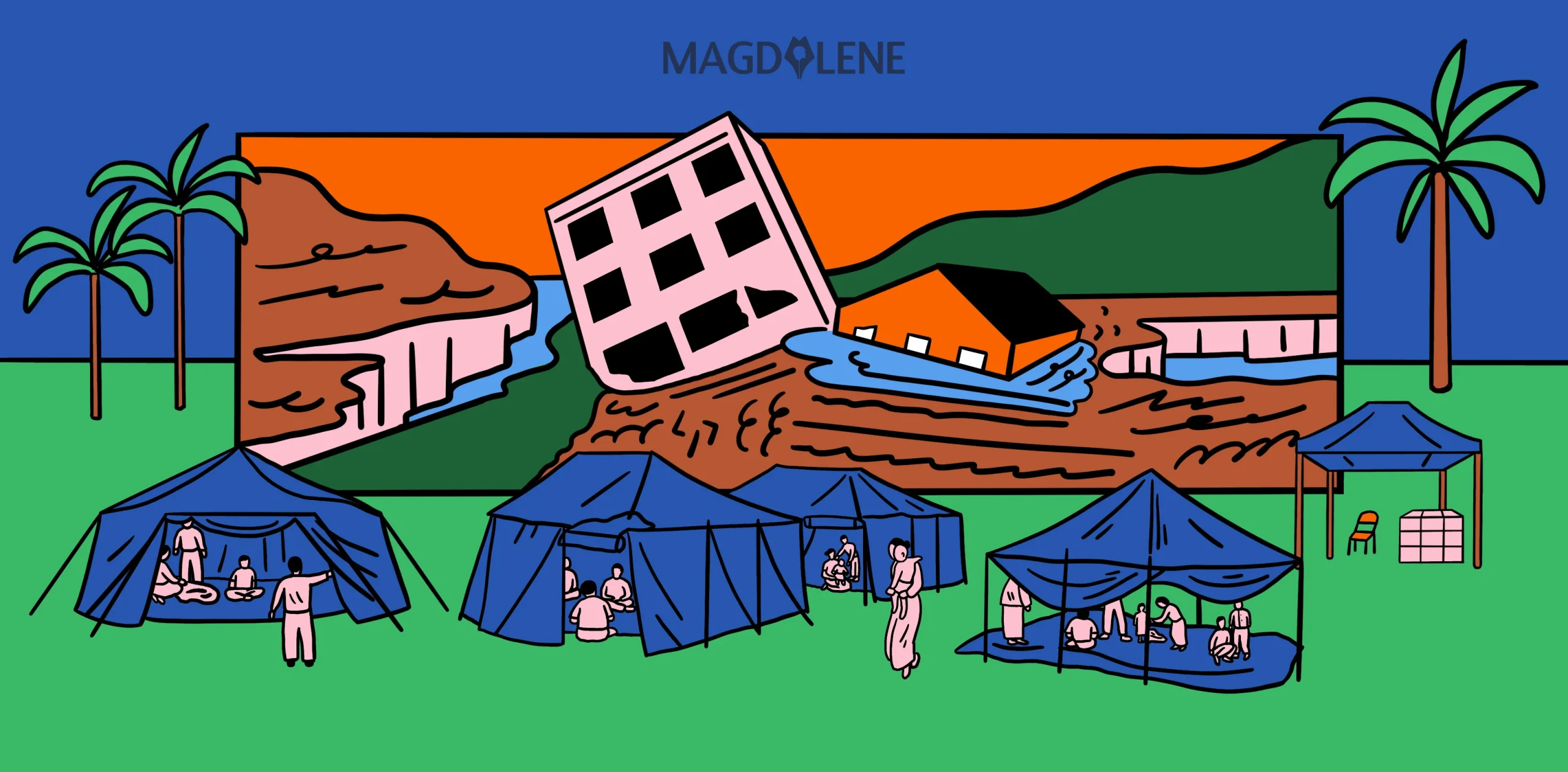

Wayan Sudra, 49, has been calling the tropical paradise of Bali home his whole life. Living just a stone’s throw away from the beach, he begins his day with a trip to the sea using his ever reliable traditional fishing boat called jukung.

As a fisherman, Wayan was dependent on the fuel-powered jukung even if hours-long exposure to fuel could lead to various health risks such as hearing problems and respiratory disorders.

“My nose stings when I inhale the smoke coming from the boats,” Wayan told Magdalene.

His fellow fishermen in Kelan Village are also not spared, with some of them complaining of hearing problems due to their constant exposure to the noise of the boat’s engine.

The harm does not stop there. Ketinting or the long-shaft engine of jukung generates around 12.5 to 17.2 carbon dioxide equivalent in a three- to five-hour trip. To offset such an amount of carbon dioxide emission, some 240 trees will be needed.

This carbon-emitting jukung was prevalent as a dependable transportation mode for Indonesian fishers because of its accessibility and compatibility.

“[Ketinting] is affordable and low maintenance with easy-to-get spare parts,” said Wahyu Muradi, spokesperson of the Marine and Fisheries Ministry. He added that engines of small-scale boats are sold freely in the market, which means ketinting meets the standards, despite its health impacts.

The World Health Organization (WHO) noted that pollutants in the air are likely to penetrate into the respiratory and circulatory systems, and further impact lungs, heart, and brain—similar effects of tobacco smoking.

Also read: ‘What Did You Eat Yesterday?’ Portrays Realistic Mature Gay Relationship

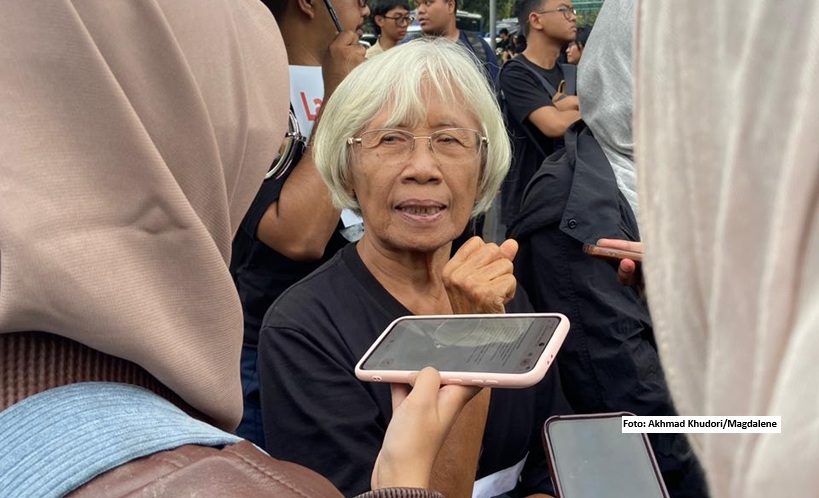

In 2018, Wayan began using a solar-powered boat donated by a woman-led social enterprise Azura Indonesia. While it took a while for Wayan to trust in the transition, the shift has granted him a less health-damaging working condition as the boat is completely silent and generates zero emission.

Even though a greener choice of transportation has been introduced to small-scale fishers in Bali, the transition is much more complex to adopt as it comes with technical, financial, and regulatory hurdles.

High demand, low income

Indonesia’s fisheries sector is a huge contributor to the gross domestic product of the world’s largest archipelago. Around seven million tons of fish are caught annually, making Indonesia the second-largest seafood producer in the world next to China.

Unfortunately, this does not automatically result in higher income for Indonesian fishermen as maintenance of fuel-powered jukung usually takes a big chunk out of their income.

Wayan, for example, needs five liters of petrol a day amounting to around IDR85,000 (US$5.44) on top of weekly oil changes at IDR45,000 (US$2.88). There are days when he is left with nothing due to high fuel costs.

But not all hope is lost. With solar as the driving energy behind Manta-One, the name of the technology brought by Azura Indonesia, a fraction of fishing operational cost could be used as a safety net to make up for the precarious nature of the job.

The maintenance of the solar-powered boat is also way less costly, allowing Wayan and his family to allocate the budget for other important things.

On top of the fishermen’s uplifted working conditions, the nature-centric solution does no harm to nature itself.

Also read: Why Indonesia is the Best Place on Earth to Fast during Ramadan

All the good things

The sun is shining all year round here in Indonesia, making the nation abundant with solar energy.

According to the 100% Renewable Energy Group research team from Australian National University, Indonesia will likely generate about 640,000 terawatt-hour per year from solar energy, outpacing the previous year’s electricity production by 2,300 times.

A self-funded social enterprise Azura Indonesia saw this opportunity back in 2018.

Co-founder Nadea Nabilla Puteri installed solar panels on top of fishermen’s boats to replace the rowdy and carbon-emitting four-stroke petrol engine with an electric propulsion engine.

It was not that easy. Nadea realised some Indonesian fishermen can’t even afford to buy their own boats, not to mention, the expensive solar panels.

So they placed solar panels in a makeshift charging station to allow fishermen to fill up their Li-ion batteries, which are used to power the boats. In only under 1.5 hours, based on the description on Azura’s website, the batteries will be fully charged to last up to three hours of sailing.

“Our target is to provide 100 units in five years ahead, cut the carbon emission by 298,000 tonnes annually, and help the fishermen have a better livelihood,” Nadea said.

From their pilot project in Kelan Village in Jimbaran, Azura Indonesia has extended their coverage to Tulamben and Amed in Bali, Banyuwangi in East Java, and Lampung in South Sumatra.

Nadea said she had presented the whole scheme to the Minister of Maritime and Investment Affairs, but there are no agreements so far.

Unlike the government, the change introduced by Azura Indonesia was welcomed by fishermen such as Wayan as they no longer need to set aside a huge amount of money for the regular maintenance of their boats.

“Since I used Manta-One in 2018, I have never had to repair and give treatments to the boat, not even once. Unlike the petrol engines, I remember the oil needs to be changed in one week’s time,” recalled Wayan.

Talking about savings, the solar panel also produces electricity for Wayan’s household. From an average monthly power bill of IDR750,000, Wayan is now paying only IDR150,000 after making the switch.

The imperfect transition

The transition to renewable energy has resulted in a number of benefits – reduced expenses, fewer health risks and minimised environmental damage.

But in return, huge adjustments had to be made.

Wayan admits the limited battery life is one of the setbacks of using Manta-One. He has to carry at least two batteries weighing 18 kg each when travelling to Nusa Dua, which is about 13 kilometers away from his home.

As for speed, Manta-One is slightly slower compared to ketinting. Wayan said that the slower speed means longer travel time to and from Kelan Village that takes up to 1.5 hours each trip.

So far, Azura Indonesia’s technology is used only by 57 fishermen – a far cry from Indonesia’s total number of fishermen at 2.23 million.

Yet the tried-and-tested approach to introduce Manta-One is best done by one-on-one, continual socialization, instead of a one-time attempt based on Azura Indonesia’s experience in presenting the new technology for coastal fishermen in a few villages in Indonesia.

As one of Azura Indonesia’s sample users, Wayan was unsure whether hop on the battery-powered boats when it was first introduced. He noted that the cable caused a mini explosion at first, a reason that Wayan suspected has been holding other fishermen back to try the boat. It was until Nadea offered to keep him company during the trip to the ocean that Wayan finally agreed to put the boat to test.

Considering that the social enterprise is still self-funded, Nadea told Magdalene that it is hardly feasible to make contact with fishermen on different islands, especially if it relies solely on individualized effort.

But in three years’ time, Azura Indonesia is planning to utilize a newly received angel investment for product improvement, additional boats placement in a few areas in Bali, and invest in people that can be in direct contact with the users. As for long-term vision, Nadea is planning to provide a scholarship for the young students in the area.

“The only thing that can help them is themselves, and the change needs to come from within,” she said.

The shift to renewable energy may be challenging age-old traditions, what is available, and what is deemed normal. It is a long shot, but the question is not whether change is feasible, but rather whether the people are willing to take a collective commitment to protect nature. The commitment needs to come from a place of care, and awareness of the importance of preserving the land that sustains us.

This story was supported by Climate Tracker.