24 Hours in a Giant Oven: How Khlong Toei’s Women Endure Deadly Heat and Lessons for Jakarta

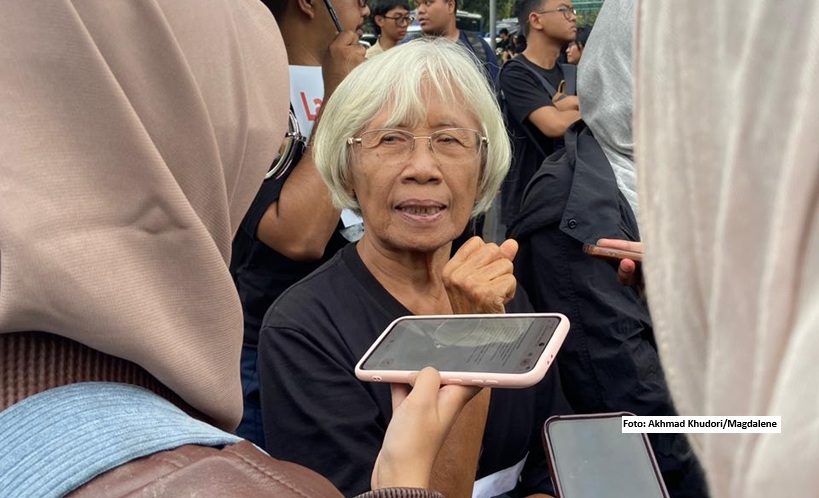

*cover: Several fans can be seen inside the shop managed by Camnong (63). (Photo by Purnama Ayu Rizky/Magdalene)

I once thought Bangkok was the ideal model of urban development, but that illusion shattered when I visited Khlong Toei on October 10, 2025. Just two Mass Rapid Transport (MRT) stops from Sukhumvit’s air-conditioned malls, Bangkok’s largest and oldest slum feels like another world. Homes, sized 12–30 square meters, are crammed under tin roofs that reflect the sun’s glare, with tangled power lines overhead, stagnant open sewers, and alleys so narrow only one motorbike can pass at a time.

The situation resembles densely populated slums like Pejagalan and Kapuk Muara in North Jakarta or Tambora in West Jakarta. But in Khlong Toei, the heat stings twice as fiercely. It’s no surprise that locals run two to four fans day and night. Air conditioners are expensive, forcing residents to dig deeper into their pockets for electricity bills, yet they offer little relief.

The air grows stifling when multiple families share one home. I visited a house occupied by seven people, including two children. A single partition separated the bathroom, while the living room doubled as a dining and sleeping area, its wide-open door providing no respite. When I arrived, children were crying, women were frantically fanning themselves, and shirtless men lay on the tiled doorstep. Fifty meters away was the home of Mon the vendor, a 62-year-old single mother who sells rice and side dishes. Her living room serves as her kitchen and livelihood, with a rusty vent in a sooty wall and a single bed in the back.

Mon the vendor’s son, a doctor working in a Bangkok hospital, urges her to move, but she refuses, feeling Khlong Toei is her home. “It’s hot, but I’m used to it, and I’ve lived here since I was a child. Besides, my needs as an elderly person are few,” she said.

During Bangkok’s hottest moments, like last year, Mon the vendor survived by drinking more water. Her fan only circulated hot air, so to avoid heatstroke, she constantly splashed water on her skin.

Mon the vendor is not alone. In Khlong Toei and many other crowded slums, women are the most vulnerable to extreme heat. The question is, how dire is their situation? And what lessons can a city with diverse, densely populated kampungs like Jakarta learn?

Also read: 24 Jam Terpanggang dalam ‘Oven Raksasa’: Bagaimana Perempuan Khlong Toei Bertahan dalam Cuaca Panas

Women’s Compounded Vulnerabilities

Bangkok’s heatwaves are increasingly deadly, especially for women. In 2024, Thailand recorded 61 heatstroke deaths by May, surpassing the 37 deaths for all of 2023, according to the Thai Ministry of Health.

In April 2024, Bangkok’s heat index reached a “dangerous” 52°C, with northern regions like Mae Hong Son hitting extreme temperatures, as reported by the World Meteorological Organisation’s State of the Global Climate 2024 (released March 2025).

In Khlong Toei, indoor temperatures can reach 39°C with high humidity. Tin roofs heat up to 68°C, disrupting sleep and drastically affecting health. When I visited the area at midday, I wore a light t-shirt and thin pants, but sweat soaked me despite holding a handheld fan.

Raja Asvanon and Variya Plungwatana from the Stockholm Environment Institute, in their article Extreme heat is worse for low-income communities: a visit to Klong Toey in Bangkok (2024), describe a unique phenomenon in Khlong Toei. They note that the urban heat island (UHI) effect raises temperatures in this slum by up to 10°C higher than surrounding areas.

Women are particularly vulnerable due to physiological and social factors. Physiologically, women have a higher body surface-to-mass ratio, less efficient sweating, and different cardiovascular responses, making them more susceptible to heatstroke, as explained by Olivia Leach and W. Larry Kenney in their study Older women more vulnerable to heat than their male peers (2024) from American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology.

I spoke with Juthamard Surapongchai, an academic from Mahidol University, Thailand, on October 8, 2025.

“Physiologically, women’s bodies are designed to be more resilient than men’s. But heatwaves still take a toll on women—not just triggering physical illnesses and reproductive health issues, but also mental health,” she emphasized.

UN Women’s How gender inequality and climate change are interconnected (2025) notes that women are 14 times more likely to die in climate disasters, with heatwaves increasing femicide by 28 percent due to economic stress. In Khlong Toei, elderly women like Mon the vendor and children experience sleep disturbances from nighttime heat, waking 2–3 times to splash cold water, impacting their mental and physical health. Yet government development policies often overlook this situation.

Also read: Bukan ‘Heatwave’, tapi ‘Hot Spells’: Penjelasan Cuaca Panas Belakangan Ini

Prateep’s Collective Solutions

Amid this crisis, the community led by Prateep Ungsongtham Hata stands as a bastion of resilience, showing how women’s leadership can transform patriarchal structures that exacerbate their vulnerabilities.

According to the community’s official website, Prateep was born in Khlong Toei in the early 1950s to a Chinese-Thai fisherman father and Thai mother. Living in an illegal home, she was denied a birth certificate and access to public schools. At 12, poverty forced her to drop out of school. She worked at the port for one baht a day, saving for night classes. At 16, she founded the One Baht School at her home.

“If they [children in Khlong Toei’s slums] can read and write, they won’t be easily deceived,” Prateep said on October 10, 2025.

In the 1970s, when the Port Authority threatened evictions, Prateep led the resistance. “We came together and stopped the bulldozers, stopped the sand dumped on our homes. Every day, my sister and I tried to educate the kids at least,” she recounted.

Her efforts gained public support, and the school was officially recognized in 1976. In 1978, she received the Ramon Magsaysay Award and established the Duang Prateep Foundation (DPF), combining Montessori education, environmental management, and firefighting training.

“We train young people in the community to put out fires, significantly reducing the number of homes burned. But we’re not satisfied—we want no fires at all, and no evictions,” she added.

The One Baht School is now relatively well-known, attracting volunteers from various countries. When I visited on October 10, 2025, dozens of children were learning through Montessori methods, trained to be active, with sharp sensory skills and critical thinking.

Mon the teacher—sharing the name of Mon the vendor in Khlong Toei—explained that the school accepts hundreds of poor students, including those from Khlong Toei, northern Thailand, and conflict areas like Myanmar and Cambodia.

“Though the fee is now 1,000 baht, parents are free to pay what they can—or nothing at all,” Mon the teacher told me.

The community also builds collective gardens and recycles waste, turning it into useful products. Prateep’s tenure as a Thai senator in 2000 amplified her advocacy for women and the urban poor. She once demanded 20 percent of the Port Authority’s land for the community that had lived there for decades.

“We asked for 20 percent of the Port Authority’s land to build our own city,” she said.

Prateep’s focus extends beyond environmental empowerment for women to supporting at-risk youth exposed to drugs and crime. She also facilitates scholarships for poor children in Khlong Toei. Mon the vendor’s son, now a doctor, is one such scholarship recipient.

Also read: Seberapa ‘Relate’ Generasi Z dengan Isu Krisis Iklim? Ini Kata Mereka

Lessons for Jakarta’s Slum

Prateep’s model offers structural solutions by combining affordable education, community participation, and environmental advocacy. This approach can be adapted to address gender inequity in cities like Jakarta amid worsening climate change.

In Khlong Toei, environmental initiatives like white-painted roofs, mini-gardens, and natural ventilation with wide-open doors are said to lower indoor temperatures by up to 11.7°C. Though not perfect, when I visited, residents had allocated land for smoke-free green spaces resembling parks with benches, and a tennis court for children and locals to maintain physical and mental health.

Near the tennis court, residents use solar-powered electricity generated by turbines in shallow community rivers. These steps could be adapted for Jakarta. “We learned ourselves that collective solutions can be effective. No wonder some choose to stay because of their strong ties to this community,” Prateep said.

Raja Asvanon and Variya Plungwatana, in the same article, warn that a 1°C temperature rise in Bangkok could cause over 2,300 additional deaths. Thus, green space interventions like those in Khlong Toei are critical amid extreme heat.

Though Jakarta hasn’t faced heatwaves, it remains vulnerable to extreme weather. According to Observer ID’s Temperature in Indonesia Projected to Rise Further in 2025 (2024), we face similar threats, with a peak temperature of 36.1°C. Magdalene has reported on the impact of extreme weather on vulnerable groups, including women, with some experiencing shortness of breath due to extreme heat.

Meanwhile, Indonesia’s policies remain insufficiently gender responsive. Gender is mentioned, but the government has yet to implement inclusive measures, as analyzed in ASEAN’s State of Gender Equality and Climate Change in ASEAN (2022). The National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) 2020–2024, even under the Prabowo-Gibran era, prioritizes economic growth over women’s vulnerabilities.

Thus, adapting Prateep’s model can begin when we can’t fully rely on the government. Prateep started with free community schools integrating climate education and women’s skills, heat and flood mitigation training, and land rights demands through women’s cooperatives. She also pushes for policies allocating funds for green spaces or guaranteeing rights for female workers, including those in the domestic sector.

As Prateep said, “We women must keep working. The question is, who else will support women if not women themselves?”

This article was produced as part of the Extreme Heat Reporting Training Fellowship by Global Climate Resilience for All.